Are Basil Leaves The Same As Bay Leaves? The Definitive Guide to Two Culinary Standouts

Are Basil Leaves The Same As Bay Leaves? The Definitive Guide to Two Culinary Standouts

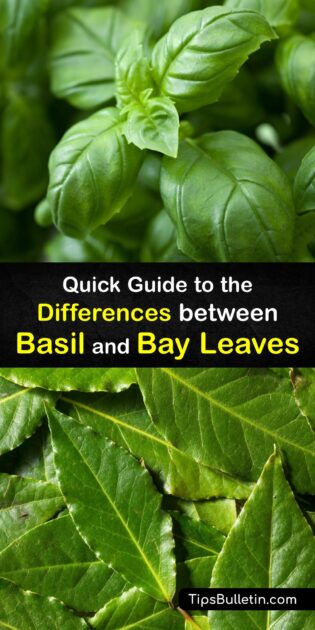

While both basil and bay leaves feature prominently in global cuisines, their identities—botanical, flavor profiles, and culinary uses—could hardly be more distinct. Basil, the sweet, aromatic herb with fragrant green or purple leaves, is a staple in Mediterranean, Southeast Asian, and Italian cooking, prized for its fresh, peppery notes. Bay leaves, in contrast, are robust, earthy, and far less flavorful in isolation, valued primarily as a subtle seasoning rather than a primary ingredient.

Yet, confusion frequently arises around whether these two leaves are interchangeable. This article clarifies everything: from their botanical origins and flavor characteristics to their practical applications and nutritional differences.

At the botanical level, basil and bay leaves belong to entirely different plant species and families.

Basil (scientifically known as Ocimum basilicum) is a tender annual herb in the Lamiaceae mint family, native to tropical regions of Asia and Africa. It typically has serrated, ovate leaves with a soft texture and volatile oils that deliver bright, slightly peppery, and citrusy aromas when crushed. By contrast, bay leaves—most commonly from the bay laurel tree (*Laurus nobilis*, family Lauraceae)—are large, thick, and leathery, with a deeply woodsy flavor and low viscosity.

“Bay leaves don’t taste like anything you’d eat whole—they’re meant to season, not stand alone,” explains food scientist Dr. Elena Marquez. “Their flavor intensity comes from slow infusion, not raw consumption.” Unlike basil, which loses potency quickly when dried or cooked, bay leaves develop their full character over hours of simmering.

Flavor distinctions define their culinary roles. Basil leaves deliver a fresh, sweet, and slightly spicy profile—its essential oils include linalool and eugenol, compounds that evoke warm Mediterranean and Thai dishes. Fresh basil brightens salads, pesto, and tomato sauces but degrades rapidly when overheated.

In contrast, bay leaves offer a subtle, camphor-linked earthiness with hints of mint and clove—flavors that deepen soups, stews, and braises without dominating. A single whole bay leaf suffices to infuse hundreds of milliliters of broth; overuse can overpower. Nutritionally, both herbs contribute minimally—basil offers antioxidants like vitamin K and flavonoids, while bay leaves contain small amounts of fiber and minerals—but neither delivers significant calories.

Culinary traditions further highlight their unique uses. In Italian cooking, basil crowns pizzas, caprese salads, and homemade pesto—its crisp leaves preserved in sweet oils or frozen. It is rarely dried, as dehydration diminishes its signature aroma.

Bay leaves, however, are non-negotiable in French *bouquet garni*, French onion soup, and retirees—though most recipes call for them to be removed before serving due to their fibrous texture. Their inclusion is ritualistic: a "holy trinity" of herbs with garlic and onion in some traditions, though bay is the quiet backbone rather than the spotlight act. Even in Indian cuisine, where bay leaves are used sparingly in curries and rice dishes like *berola patta*, they never replace the vibrant freshness of cilantro or basil.

Misidentification often stems from appearance alone. Both are green, lanceolate, and semi-ponytailed, but key differences emerge under scrutiny. Basil leaves are thinner, with soft margins and a velvety surface; bay leaves are thicker, glabrous (smooth), and serrated with a leathery texture.

Color variation—basil showing purples or reds in some varities, bay leaves uniformly dark green—adds to the visual confusion, yet these traits don’t reflect edibility. “Many students assume dried basil equals dried bay, or vice versa,” notes culinary historian Dr. Amara Patel.

“But once you taste the contrast—basil’s bright, fleeting sweetness versus bay’s lingering, woody depth—you know the distinctness.”

Even within home kitchens, practical missteps blur their boundaries. Recipes calling for “one bay leaf” are sometimes mistakenly interpreted as base herbs, leading cooks to add torn basil accidentally. “This isn’t just a flavor mistake—it changes the entire harmony,” warns chef Miguel Torres.

“Basil’s brightness lifts a dish; bay’s warmth grounds it, but never replaces.” Always check recipes: if heat will mellow the ingredient over time, bay leaves are safe. For fresh punch, basil—whether torn over pasta or folded into a sauce—remains irreplaceable.

Storage and shelf life reinforce their differences.

Fresh basil wilts quickly; it must be kept refrigerated, often wrapped in a damp paper towel, to preserve its aroma. Bay leaves, dried and tightly sealed, last far longer—months even years if kept in a cool, dark place. This longevity underpins their return as pantry staples, unlike basil, which is best consumed within days of purchase.

Health considerations vary subtly. Basil contains anti-inflammatory compounds, including rosmarinic acid, linked to immune support and respiratory benefits. Its high vitamin K content supports bone health.

Bay leaves, while lower in vitamins, release antioxidants like parthenolide when infused, traditionally associated with circulation and digestion. However, neither should replace whole-food nutrition—both enhance but do not substitute for vegetables, grains, and other nutrient-dense sources. Overindulgence with bay leaves, especially when consumed dry, risks inflation or mild gastrointestinal discomfort, whereas basil allergies, though rare, can provoke reactions.

Global culinary diversity ensures neither herb dominates globally. In Southeast Asia, basil—like Thai holy basil or Indonesian soursop-infused varieties—shines in curries and salads, often paired with lemongrass and galangal. Bay leaves, while used in curries and broths across South Asia, remain secondary.

In contrast, Mediterranean kitchens place basil at the center of summer fare, while bay leaves quietly anchor comfort dishes like French *vin ale* or Middle Eastern broths. East Asia favors fermented or savory combinations, where basil seldom enters, leaving bay’s earthy notes as the best-suited mellowing agent.

Cooking demonstrations offer vivid proof of their divergence.

A typical herb comparison: basil’s leaves wilt and darken within seconds when boiled, releasing aromatic vapors; bay leaves shed moisture slowly, deepening slowly as flavor migrates into liquid. “You can feel the difference in texture and aroma,” says professional chef Luca Rossi. “Basil screams for fresh use; bay demands patience—it’s a slow finisher.”

Cultural symbolism strengthens their identities.

Basil carries religious significance in Christianity, symbolizing devotion and love, and appears in Renaissance art and poetry. Bay leaves represent victory and wisdom—ancient Greeks crown athletes; Roman soldiers wear laurel wreaths. These narratives reinforce their roles: basil as a sensory joy, bay as a timeless explorer of flavor depth.

Botanical Classification: A Definitive Breakdown

Origin and Taxonomic Identity

Basil is classified under the genus Ocimum, primarily *Ocimum basilicum* (sweet basil) and variants like Thai or African basil. It belongs to the mint family (Lamiaceae), known for aromatic foliage. Bay laurel, by contrast, is *Laurus nobilis*, part of the laurel family (Lauraceae), which includes tropical and subtropical trees adapted to Mediterranean climates.

Unlike basil, bay laurel is evergreen, with glossy, uniseriate leaves evolving from dense clusters. Botanist Dr. James Craig states, “The taxonomic gulf explains why their tastes, textures, and uses diverge so fundamentally—basil’s herbaceousness vs.

bay’s resinous toughness.”

Related Post

Xtale Cross Fur Roblox: The Ultimate Hybrid Gear Refining Fantasy Meets Function

Washington, D.C.’s Frontline Role in Protecting Social Security Beneficiaries

AMD CPUs: Architecting Innovation Through Decades of Release Order

Usps Hold Mail: How to Temporarily Suspend Your Mail Delivery and What It Really Means for Recipients