Can Bacteria Be Eukaryotic? Unraveling the Fundamental Divide in Life’s Architecture

Can Bacteria Be Eukaryotic? Unraveling the Fundamental Divide in Life’s Architecture

Bacteria, ancient and ubiquitous, represent one of the oldest forms of life on Earth—single-celled, membraneless organisms governed by prokaryotic biology. In stark contrast, eukaryotes—encompassing everything from plants and animals to fungi and protists—feature complex cellular structures including a defined nucleus and organelles, a legacy of billions of years in evolutionary refinement. For decades, scientists have debated whether bacteria, despite their foundational role in ecosystems, possess any latent or emergent eukaryotic traits.

The short answer is no: bacteria are fundamentally distinct in their cellular organization, genetic architecture, and evolutionary trajectory, firmly placing them outside the eukaryotic domain. Yet, the nuances of their biology spark profound insights into life’s diversity and the boundaries between the simplest and most complex cellular life.

At the structural core, the distinction is clear.

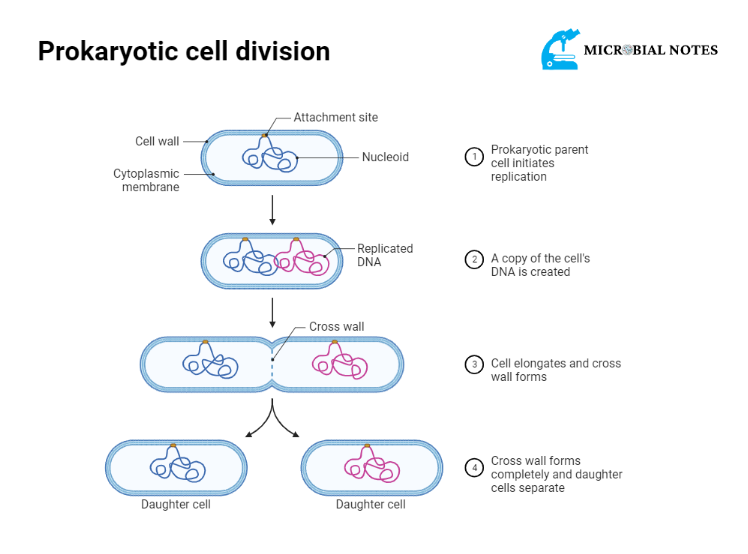

Eukaryotic cells are defined by internal membrane-bound organelles, including the nucleus that houses genetic material. Bacteria, by contrast, lack this compartmentalization—their DNA exists as a single, circular molecule suspended freely in the cytoplasm, devoid of nuclear membranes or associated structures. This architectural simplicity defines a primary boundary: eukaryotes evolved increased complexity through membrane invaginations, resulting in multi-layered cellular organization.

“The absence of membrane-bound organelles remains the most defining feature distinguishing eukaryotes from prokaryotes like bacteria,” explains Dr. Elena Marquez, a microbial evolutionary biologist at the Max Planck Institute for Terrestrial Microbiology. “Without this innovation, bacteria cannot acquire the structural hallmarks of eukaryotic cells, no matter environmental pressures.”

Genetically, the contrast deepens.

Eukaryotic genomes are organized on linear chromosomes enclosed within nuclei, enabling sophisticated regulation of gene expression through chromatin remodeling and alternative splicing. Bacterial genomes, while compact and efficient, exist as circular chromosomes without such layers of control. Furthermore, eukaryotes typically utilize linear RNA polymerases with specialized subunits and splicing machinery—features absent in bacteria.

As Professor James Wu from MIT’s Department of Biology notes, “The genetic control systems in eukaryotes reflect a level of regulatory precision that arises from cellular complexity itself—something bacteria never evolved.” Horizontal gene transfer, common in bacterial evolution, remains limited in its capacity to restructure fundamental cellular machinery beyond minor genomic additions.

Yet, over the past quarter-century, advances in molecular biology and genomics have revealed fleeting shadows of complexity in bacterial physiology. Some species exhibit unusual structural features: filamental arrangements resembling microtubule-like cytoskeletons, intricate protein-based cytoskeletons allowing motility and division, and quorum-sensing networks suggesting coordinated group behavior akin to early eukaryotic signaling.

However, these phenomena remain developmental adaptations within strict prokaryotic boundaries. No bacterium has been documented with a true nucleus, membrane-bound vesicles, or organelle-specific functions. “Even in the most complex bacterial communities, such features do not equate to eukaryotic cellular identity,” clarifies lipid biochemist Dr.

Anika Patel. “These architectures are superficial exceptions, not fundamental shifts in cellular architecture.”

Another common misconception stems from horizontal gene transfer (HGT), where bacteria acquire genes from distantly related organisms, sometimes even incorporating eukaryotic-like sequences. For instance, certain bacteria share metabolic genes with eukaryotes, and some marine isolates possess foreign DNA integral to stress response.

But HGT influences specific functions, not cellular blueprint. The core machinery—inheritance, compartmentalization, nuclear division—remains intact. “Acquiring a eukaryotic gene does not transform a bacterium’s prokaryotic genome into one resembling that of a protist,” stresses evolutionary geneticist Dr.

Igor Volk at the Russian Academy of Sciences. “Eukaryogenesis is not merely gene acquisition; it is a wholesale reconfiguration of cellular life.”

Beyond genetics and structure, metabolic efficiency underscores the eukaryotic advantage. Eukaryotes efficiently segregate energy-producing processes—respiration in mitochondria, nutrient synthesis in vesicles—allowing greater adaptability in diverse environments.

Bacteria dominate through rapid reproduction and sparse complexity, excelling in niches but lacking the integrated resource management seen in eukaryotes. This efficiency is not just structural; it shapes ecological dominance and biotechnological potential. Synthetic biologists now engineer eukaryotic-like behaviors into bacteria—such as programmed cell differentiation—but these remain synthetic constructs, not natural transitions.

To assess whether bacteria could ever evolve toward eukaryotic form, experts emphasize evolutionary certainty. The path from prokaryote to eukaryote—believed to have involved engulfment of an Alpha-proteobacterium into a host archaeon—required hundreds of millions of years of incremental complexity. No known mechanism permits a strictly prokaryotic cell to spontaneously reorganize into a eukaryotic architecture without ancestral eukaryotic traits propagating first.

“Life’s complexity is cumulative,” asserts Dr. Marquez. “Once you lose the membrane barrier and develop multilayered control, the evolutionary road diverges sharply.”

While bacteria remain firmly eukaryotic out of classification, their biology challenges and enriches our understanding of cellular evolution.

Each discovery—novel cytoskeletal analogs, strange cooperative behaviors—highlights the plasticity of life. Yet inside their molecular machinery, bacteria remain defined by their prokaryotic heritage. They are not just simple cells; they are the ancestral building blocks of all complex life, but not precursors to eukaryotes.

The boundary is not blurred—it is definitive, revealing the deep roots of cellular diversity and the rarity of true eukaryotic innovation.

Understanding bacteria’s place as unequivocally prokaryotic reshapes how scientists approach origins of complexity, synthetic biology, and even astrobiology’s search for alien life. While the dream of “bacterial eukaryotes” captures imagination, the truth lies in distinction: the elegant simplicity of bacteria contrasts sharply with the intricate order of eukaryotes, a duality that defines life’s spectrum.

In this light, bacteria are not just bacteria—they are the ancestral fire that, through time, diversified into the vast, complicated world of eukaryotic organisms.

Related Post

Unlock Streaming Mastery: How the YouTube TV App Redefines TV Watching in 2024

How to Navigate Yuppentek 1 Tangerang SMA Profile: Mastering PPDB Biaya Masuk Registration

Btd4: The Strategic Blueprint Transforming Industry Standards and Digital Innovation

Redwood County Jail Rostertimeline & Friends2MN: Unlocking the Rostersetimeline Inmate Search