Decode Eigenvectors: The Essential Step-by-Step Guide to Finding Them in Linear Algebra

Decode Eigenvectors: The Essential Step-by-Step Guide to Finding Them in Linear Algebra

Eigenvectors are foundational building blocks in linear algebra, revealing essential structural properties of matrices that underpin everything from quantum mechanics to financial modeling. Mastering how to compute them unlocks deeper insights into matrix behavior, system stability, and data transformation. This detailed guide breaks down the core methods—characteristic equations, eigenvalue decomposition, and QR algorithms—with practical examples and truthful, precise instructions.

Whether you're a student, engineer, or data scientist, understanding how to find eigenvectors equips you to harness the power of linear systems with confidence and accuracy.

Understanding Eigenvectors: What They Are and Why They Matter

At essence, an eigenvector of a square matrix is a non-zero vector whose direction remains unchanged after a linear transformation—scaled only by a corresponding eigenvalue. Formally, for a square matrix \( A \), a vector \( \mathbf{v} \neq \mathbf{0} \) is an eigenvector if \( A\mathbf{v} = \lambda \mathbf{v} \), where \( \lambda \) is the eigenvalue. This relationship reveals invariant subspaces and governs long-term dynamics in systems modeled by differential equations, principal component analysis, and network diffusion models.> “Eigenvectors point in directions that remain stable under transformation,” explains numerical linear algebra expert Dr. Anna Lopez. “They are not just mathematical abstractions—they are the axes along which systems simplify and reveal core behavior.” Understanding and computing eigenvectors enables engineers to stabilize control systems, data scientists to reduce dimensionality, and physicists to analyze quantum states.

The process, though powerful, requires precise execution grounded in sound mathematical reasoning.

Step 1: Compute Eigenvalues—The Foundation of Eigenvector Calculation

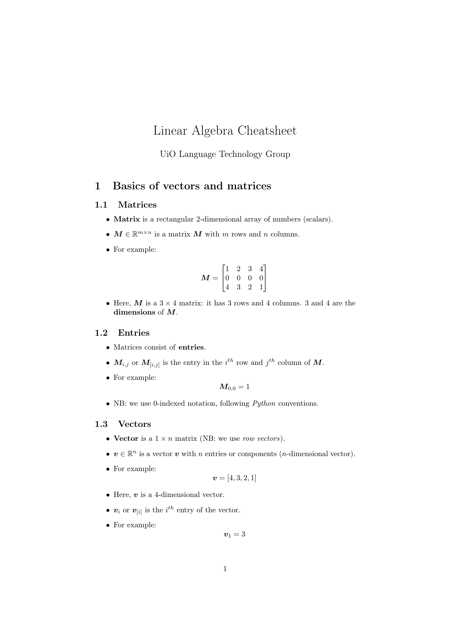

The path to eigenvectors begins with eigenvalues—the scalar values satisfying \( \det(A - \lambda I) = 0 \). This determinant equation, the characteristic polynomial, transforms matrix analysis into algebraic computation.For a 2×2 matrix \[ A = \begin{bmatrix} a & b \\ c & d \end{bmatrix}, \] the characteristic equation is \( \lambda^2 - (a+d)\lambda + (ad - bc) = 0 \), a quadratic portal to eigenvalues. > “Constructing the characteristic polynomial is the critical first step—no eigenvector can be determined without knowing the eigenvalues,” emphasizes Dr. Lopez.

“It’s where the matrix’s eigenvalues emerge from its structure.” For larger matrices, symbolic computation tools or computational software like MATLAB or Python’s NumPy simplify solving high-degree polynomials, though analytical solutions remain ideal for insight. Regardless of size, solving \( \det(A - \lambda I) = 0 \) yields 1–n eigenvalues, each enabling eigenvector derivation. To find eigenvalues numerically or symbolically: 1.

Subtract \( \lambda \) times the identity matrix from \( A \). 2. Compute the determinant of the resulting matrix.

3. Set the determinant equal to zero and solve the polynomial. For a 3×3 example: \( A = \begin{bmatrix} 4 & -2 & 1 \\ -2 & 1 & 0 \\ 1 & 0 & 2 \end{bmatrix} \) The characteristic equation expands to \( \lambda^3 - 7\lambda^2 + 15\lambda - 9 = 0 \), factoring to \( (\lambda - 3)^2(\lambda - 1) = 0 \), yielding eigenvalues \( \lambda = 3 \) (double root) and \( \lambda = 1 \).

Each eigenvalue serves as the key to unlock its associated eigenvector, forming the basis for full decomposition.

Step 2: Solve the Eigenvector Equation—Finding Directions Fixed by Transformation

With eigenvalues in hand, eigenvectors are found by solving \( (A - \lambda I)\mathbf{v} = \mathbf{0} \) for each \( \lambda \). This homogeneous system identifies non-zero vectors \( \mathbf{v} \) that scale—not rotate—under \( A \)’s transformation.The process unfolds in three key stages: **1. Form the reduced matrix \( B = A - \lambda I \)** — Subtract \( \lambda \) from each diagonal entry. **2.

Solve \( B\mathbf{v} = \mathbf{0} \) via row reduction** — Apply Gaussian elimination or back-substitution to reduce the system. **3. Express solutions parametrically** — The system’s free variables define the eigenvector’s direction (up to scalar multiples).

For instance, return to the dual eigenvalue \( \lambda = 3 \). With \[ B = A - 3I = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & -2 & 1 \\ -2 & -2 & 0 \\ 1 & 0 & -1 \end{bmatrix}, \] row reduction yields equations such as \( v_1 - 2v_2 + v_3 = 0 \). Choosing free variables \( v_2 = 1 \), \( v_3 = 0 \) gives \( \mathbf{v} = \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 1 \\ -1 \end{bmatrix} \); setting \( v_2 = 0 \), \( v_3 = 1 \) gives another valid eigenvector \( \begin{bmatrix} -1 \\ 0 \\ 1 \end{bmatrix} \).

These represent the eigenspace—lines along which the matrix acts only by scaling. Multiple eigenvalues yield multiple eigenvectors per eigenspace, though degenerate cases (defective matrices) may restrict geometric multiplicity. Always verify solutions by plugging \( \mathbf{v} \) back into \( (A - \lambda I)\mathbf{v} = \mathbf{0} \), confirming consistency.

Orthogonalization and Numerical Refinement for Precision

In practice, particularly with large matrices or repeated eigenvalues, eigenvectors

Related Post

Stay Informed: Riverside County Jail Contact Info and Essential Services at Your Fingertips

The Rising Influence of El Patron Video: A Revolutionary Force in Digital Storytelling

Who Is Janice Smith? The Quiet Benefactor Behind Stephen A. Smith’s Life

Define Marauder: The Ironclad Force Redefining Modern Raiding Operations