Defining Population Biology: The Science That Shapes Our Understanding of Life’s Numbers

Defining Population Biology: The Science That Shapes Our Understanding of Life’s Numbers

At its core, Population Biology is the scientific discipline dedicated to studying the characteristics, dynamics, and interactions of biological populations—groups of organisms of the same species living in a defined geographic area. Far more than a mere census of numbers, this field explores how populations grow, shrink, adapt, and respond to environmental pressures, making it a cornerstone of ecology, evolutionary biology, and conservation science. As ecosystems worldwide face unprecedented stress from climate change, habitat loss, and human activity, Population Biology Definition has become critical for predicting how species survive—or falter—in a rapidly changing world.

Understanding a population’s structure begins with foundational metrics. Two key indicators define population health: population size, the total number of individuals, and population density, the number per unit area. These figures shape how scientists assess viability, reproductive rates, and genetic diversity.

For example, a sparse population of African elephants in fragmented forests signals vulnerability to inbreeding and local extinction, whereas a dense population of migratory birds in spring may reflect favorable breeding conditions.

Population dynamics—the changes in these numbers over time—are driven by four interconnected processes: birth rates, death rates, immigration, and emigration. Each influences population size but also shapes genetic composition and evolutionary potential.

High birth rates with low mortality can trigger rapid expansion, while sudden increases in mortality—often due to disease or environmental catastrophe—trigger sharp declines. Immigration, the arrival of individuals from other populations, introduces genetic variation, while emigration can reduce genetic load or trigger dependency on external gene flow.

One of the most powerful tools in the Population Biology Definition arsenal is the Lotka-Volterra model, which mathematically describes predator-prey relationships and competition between species. These models, though simplified, provide essential insights into oscillating population cycles seen in nature—from lynx and hare population fluctuations to plankton blooms followed by predator booms.

“Population models don’t predict the future with certainty,” notes Dr. Elena Marquez, a leading ecologist at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute. “But they reveal patterns, test hypotheses, and expose the fragility or resilience embedded in ecological relationships.” The concept of carrying capacity—maximum population size an environment can sustain—remains central to Population Biology.

Driven by limited resources like food, water, and space, carrying capacity determines whether growth slows, stabilizes, or crashes. In human contexts, this principle directly informs urban planning and public health strategies. In wildlife management, exceeding carrying capacity often leads to starvation, disease, and territorial conflict, as seen in overpopulation events of white-tailed deer across North America.

Genetic variation within populations is another critical pillar. High diversity enhances adaptive capacity, allowing species to evolve in response to stressors like warming temperatures or novel pathogens. Conversely, genetic bottlenecks—dramatic reductions in population size—erode this flexibility, increasing extinction risk.

Conservation genetics, a subfield rooted in Population Biology, uses DNA analysis to guide breeding programs and habitat corridors that boost gene flow between isolated groups. “Genetic health is survival health,” emphasizes Dr. Raj Patel, a population geneticist at Stanford.

“Without diversity, populations lose their ability to adapt.” Human activities have dramatically altered population dynamics across the globe. Deforestation fragments habitats, isolating species and reducing successful migration. Pollution and overfishing skew natural selection, favoring resilient but often less fit organisms.

Climate change accelerates shifts in range, forcing species to migrate poleward or to higher elevations—an ongoing challenge documented in polar biologists tracking Arctic fox versus red fox encroachment. “We’re witnessing evolutionary responses at an unprecedented pace,” says Dr. Lila Chen, an ecologist studying urban-adapted species.

“Population Biology helps us see which species can shift, and which cannot.” Field methodologies continue to evolve, blending traditional surveys with cutting-edge technology. GPS tagging tracks animal movements across continents, genetic sampling identifies hidden population structures, and remote sensing maps habitat changes in real time. Machine learning models now predict population trends from decades of dataset, enabling proactive conservation interventions.

“Technology transforms raw data into actionable insight,” explains Dr. Felix Reed, director of the Global Biodiversity Initiative. “It turns population biology from a descriptive science into a predictive and preventive one.” Applications of Population Biology extend beyond academia and conservation.

Policymakers rely on population projections to design sustainable fisheries, manage wildlife corridors, and allocate resources for endangered species. The IUCN Red List, a globally recognized authority on species risk, depends heavily on demographic analysis rooted in population biology principles. Even agriculture benefits: understanding pest population dynamics enables targeted, eco-friendly pest control that minimizes harm to beneficial species.

Emerging research increasingly links Population Biology with social and economic systems. Human population growth, urban sprawl, and consumption patterns directly influence wildlife populations, creating feedback loops where ecological health affects public welfare. “There is no planet B,” underscores Dr.

Amara Nkosi, a population ecologist at the University of Cape Town. “To sustain human societies, we must first safeguard population stability in nature.” Her work integrates demographic modeling with socioeconomic data, revealing how education, healthcare access, and environmental policy jointly shape population resilience. Effective conservation hinges on a nuanced grasp of these dynamics.

Success stories, such as the recovery of the gray wolf in the northern Rockies, illustrate how reintroduction and habitat restoration, informed by population biology, can restore balance. Conversely, persistent declines in amphibians and pollinators highlight gaps in understanding and response.

In essence, Population Biology Definition encapsulates a profound and urgent science—one that deciphers the rhythm of life in numbers, exposes the invisible forces shaping species survival, and guides humanity toward a balanced coexistence with nature.

As pressures mount, the discipline’s clarity in measuring and predicting population trends becomes not just academic, but essential for sustaining the intricate web of life. Understanding populations is not an abstract exercise; it is the foundation for protecting biodiversity, ensuring food security, and securing a viable future for both people and the planet. The science of Population Biology, defined by dynamic interaction and rigorous analysis, is indispensable in unraveling how populations endure, adapt, and vanish—reminding us that every individual count matters in the grand equation of life.

Related Post

Unfaithful Husband Punished: The Legal and Emotional Fallout of Betrayal

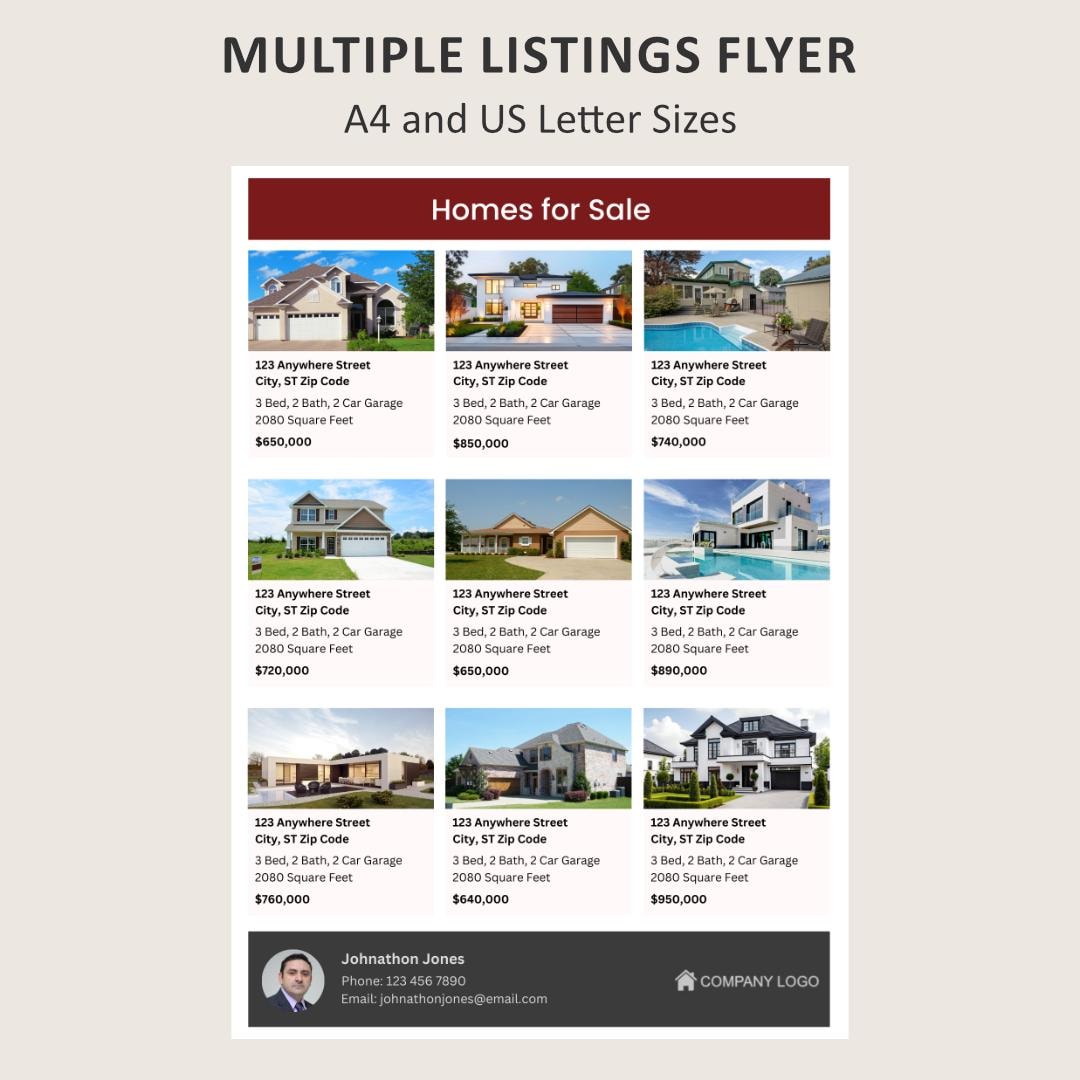

The Hidden Garage Trend in LA: How COM’s Guest Multiple Listings Unravel Hidden Real Estate Opportunities

When Deception Deceived: The Trojan Horse and the Art of Hidden Danger