Do Not Go Gentle: Unpacking the Enduring Power of Dylan’s Rebellion in Poetry

Do Not Go Gentle: Unpacking the Enduring Power of Dylan’s Rebellion in Poetry

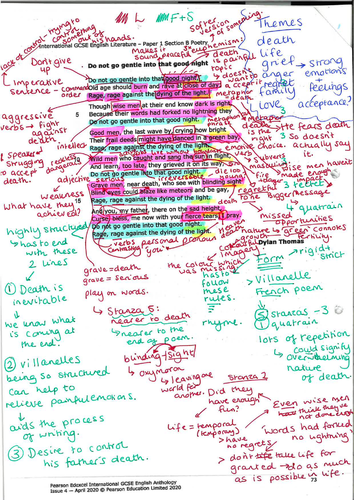

In a world constantly urging restraint, reflection, and relapse, Dylan Thomas’s *Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night* stands as a defiant clarion call to resist quiet surrender—especially in the face of death. More than a mere elegy, the poem is a visceral plea, urging the terminally ill to fight, to rage, to live until the end, rejecting fatalism with raw emotional urgency. The phrase “Do not go gentle” functions not as a passive warning but as an active challenge—a pas de deux between life and death, between surrender and rebellion.

Thomas’s poem emerged from personal grief, written in the final year of his life amid battling lung cancer, yet its resonance transcends private sorrow. It taps into a universal human tension: the fear of non-being versus the will to survive. Through forceful repetition and urgent imagery, the poem distills a philosophy of resistance.

The repeated imperative “Do not go gentle” becomes a tragic mantra, holding within it both vulnerability and defiance—a subtle but powerful duality.

The Poem’s Core Message: Rebellion as a Moral Duty

At its heart, *Do Not Go Gentle* reframes death not as a natural, serene end but as a potential betrayal—an unjust act that demands defiance. The poem opens with a portrayal of aging, frailty, and waning power: “Old age should burn and rdew / Old age should blast the skeleton’s bones,” yet Thomas refuses to accept decline.The “r vitality” of life must be preserved, not surrendered. The central demand is clear: “rage, rage against the dying of the light”—a phrase that blends visceral emotion with moral urgency. This call to “rage” is not about anger for its own sake but about honoring the intensity of lived experience.

The poem identifies three types of men who “rage” fiercely: wise men who rage, wise and wild men who “burn bright,” and those who rush toward death without struggle. The most revered, “wise men,” “rage” not with recklessness, but with full awareness—aware that time is finite, aware of death’s inevitability, yet determined to fight. The poem insists: “Death’s the end, but rage is freedom.”

- The intensity of “wise men” lies in their ability to confront mortality with clarity.

They “rage” not out of fear, but out of love for what life has meant.

- The “wild” rebels—described as “burning and r influencing the stars”—symbolize a desperate, passionate embrace of life’s final moments, akin to fuel throwing combustion to flame.

- Even those “rush and die” without struggle represent a tragic failure, warning against passive resignation.

The refrain “Do not go gentle” grounds the poem, turning personal lament into universal command.

Literary Craft and Emotional Resonance

Thomas crafts the poem with lyrical precision and emotional gravity. His use of imagery—“death’s bad Uhr,” “dying of the light,” “wild and sentimental old men”—evokes both the fragility and dignity of aging.The ancient Greek-derived phrase “Gods burn” (replacing modern “burn” in some editions, though Thomas often uses “die” directly) collapses classical myth with intimate struggle, embedding the mortal fight in a timeless struggle between fate and will. The repetition of “rage” serves as the poem’s emotional engine, propelling each stanza into deeper intensity. Each variation builds on the last: from aging men to “wild” ones, to those who flee quietly.

Only the “wise” find their fierce vitality—they battle the darkness not in ignorance, but in full knowledge, thereby reclaiming agency. The emphasis on “wisdom” suggests that rage need not be reckless; it can be thoughtful, profound defiance. While not overtly religious, the poem carries sacred weight.

It positions death not as liberation but as loss—implicitly urging reverence for life’s preciousness. The fight against surrender becomes a spiritual act, a testament to what it means to truly live.

The Poem’s Legacy and Cultural Impact

Since its publication in *The Knox Review* in 1951, *Do Not Go Gentle* has become one of the most studied and quoted poems in modern English literature.Its return to “r” in later selections—“Do not go gentle into that good night”—coined one of the most memorable openings in poetry. The phrase has entered popular culture, referenced in films, music, and everyday conversations about perseverance. The poem’s lasting power stems from its raw authenticity.

Thomas transforms private grief into public testimony. His voice, mature but urgent, appeals not just to the dying, but to anyone who has ever hesitated in the face of loss, illness, or change. It is a message of resilience wrapped in elegy—neither naive optimism nor despair, but a balanced call to honor life’s intensity.

Experts on 20th-century poetry note that Thomas transcends traditional elegiac forms. Where elegiac poetry often mourns with sorrow, *Do Not Go Gentle* ignites with fury. It rejects passive acceptance, framing resistance as both right and reverence.

This synthesis of grief and defiance gives the poem its uniqueness: a bridge between intimacy and universality, between sorrow and spark. Ultimately, “Do Not Go Gentle” endures not merely as a stall against death, but as a celebration of living fully, fiercely, and without reluctance. It invites readers not just to endure, but to rage—with heart, with clarity, with unyielding life—until the final breath.

Reflections on the Philosophy

The poem’s enduring relevance lies in its recognition of human complexity. It acknowledges that aging and illness bring physical decline, but it also affirms that identity, will, and love persist. “Do not go gentle” accepts death’s inevitability yet insists on the value of resistance.In doing so, Thomas offers a philosophy of living: death need not be an end, but a conclusion to a life truly witnessed. This philosophy resonates amid modern anxieties about mortality, aging, and quality of life. In an age obsessed with longevity and avoidance, the poem’s urgency feels both timely and timeless.

It asks not only readers to reflect, but to act—to “rage” in their own lives through gratitude, creativity, and connection. Thomas’s verse does not promise immortality, only that life, when lived fiercely, leaves an indelible imprint. In “Do Not Go Gentle,” resistance becomes love’s purest

Related Post

The Transformative Power of Abito: Reshaping Urban Renewal and Sustainable Living

Azan Zuhur Unveiled: The Sacred Noon Prayer and Its Spiritual Significance in Islamic Tradition

Error Code 280: The Stealthy Barrier Blocking Your API Requests

Unblocked Football Games: Where Every Match Is Playable Without Restrictions