Does a Prokaryotic Cell Have a Nucleus? Unraveling the Core Mystery of Life’s Simplest Units

Does a Prokaryotic Cell Have a Nucleus? Unraveling the Core Mystery of Life’s Simplest Units

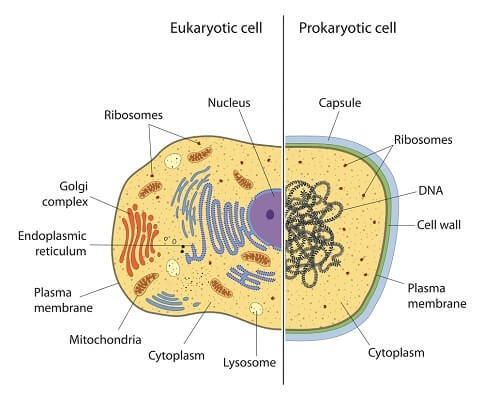

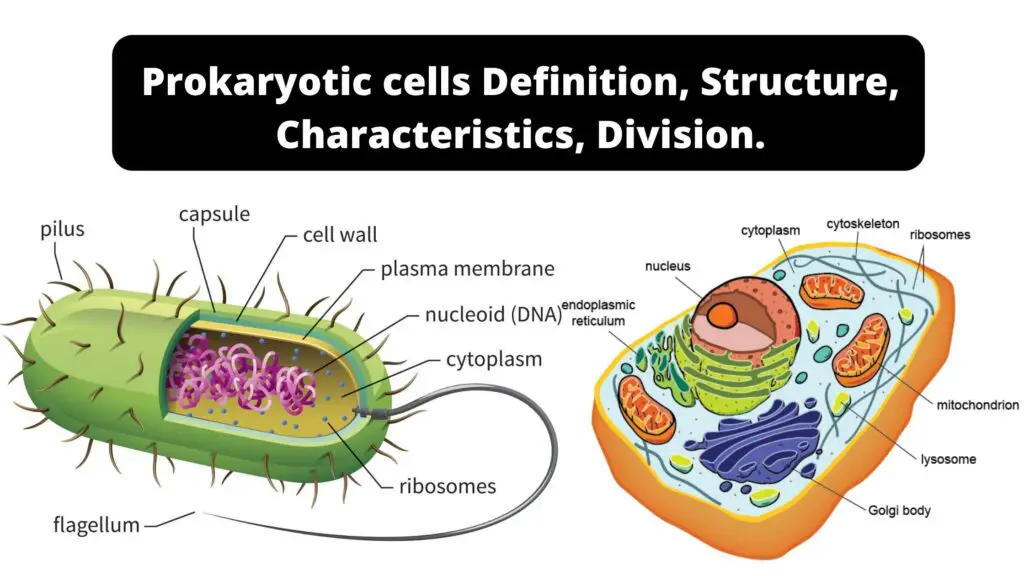

At the heart of one of biology’s most fundamental debates lies a deceptively simple question: Does a prokaryotic cell possess a nucleus? Unlike their complex eukaryotic counterparts, prokaryotes—dominated by bacteria and archaea—lack a membrane-bound nucleus, a defining feature that shapes their biology, evolution, and function. While eukaryotic cells organize genetic material within a protected nucleus, prokaryotic cells operate under a different paradigm, one that challenges assumptions about cellular organization and efficiency.

Understanding this distinction is critical to grasping how life diverged and adapted across millennia. A nucleus serves as the cellular command center in eukaryotes, safeguarding DNA, regulating gene expression, and coordinating complex cellular processes. In contrast, prokaryotic cells contain no such compartment.

Their genetic blueprint—the circular chromosome—is suspended freely in the cytoplasm within a region known as the nucleoid, yet this structure bears no resemblance to a true nucleus. “The nucleoid lacks a surrounding membrane and the associated proteins typical of nuclear division,” explains molecular biologist Dr. Elena Rodriguez.

“Without a nuclear envelope, DNA replication, repair, and transcription occur in a comparatively unstructured, yet highly regulated, environment.”

One of the key reasons prokaryotes evolved without a nucleus lies in their need for rapid growth and division. These cells often reproduce every 20 minutes under optimal conditions, a pace that demands streamlined molecular processes. “They sacrifice compartmentalization to accelerate metabolic activity,” notes researcher Dr.

James Kwon. “The absence of a nucleus allows direct coupling between DNA processes and cellular functions—a survival advantage in fast-paced environments like soil, water, or the human gut.” This efficiency, however, comes with trade-offs: vital regulatory mechanisms present in eukaryotes are absent or simplified in prokaryotes.

Structurally, the prokaryotic nucleoid is defined not by membranes but by protein complexes that organize and protect DNA.

Proteins such as HU, H-NS, and nucleoid-associated proteins bind DNA into compact domains, facilitating processes like replication and transcription without membrane barriers. These proteins stabilize genetic material, prevent damage, and assist in chromosome segregation during cell division—functions once thought exclusive to nucleus-containing cells. “These proteins act as molecular scaffolds,” says Kwon.

“They create order where a membrane would otherwise exist, enabling precise control despite the lack of boundaries.”

This structural simplicity influences gene regulation. Prokaryotic cells rely on bedside control—promoters, operators, and repressors—directly modulating transcription in response to environmental cues. There is no nuclear “traffic system” to delay or filter genetic instructions; instead, gene expression shifts rapidly in real time.

As Dr. Lena Torres, a microbiologist at Stanford, explains, “In prokaryotes, regulation doesn’t wait for membrane transport—it’s immediate. The lack of a nucleus enables a responsive, adaptive lifestyle, perfectly suited to fluctuating conditions.”

Beyond biology, the absence of a nucleus reshapes how prokaryotes interact with their surroundings.

Without a segregated nucleus, the cell’s DNA is immediately exposed to cytoplasmic factors, fostering unfiltered interaction with proteins, RNA, and metabolic enzymes. This transparency fuels efficient repair mechanisms and swift adaptation—features central to the evolutionary success of bacteria and archaea, which have populated Earth’s extremes for billions of years. “Their genome is both shielded and exposed,” says Torres.

“This duality makes them resilient pioneers in ecological succession and biotechnological innovation.”

Significantly, the prokaryotic nucleoid challenges long-held notions about cellular complexity. Once viewed as primitive, prokaryotic cells reveal sophisticated mechanisms for organizing life without a nucleus. Their genetic architecture demonstrates that complexity is not inherently tied to compartmentalization—efficiency, adaptability, and resilience can emerge through alternative design principles.

The physics of diffusion, the logic of protein-mediated control, and the economy of unencapsulated genomes all converge to sustain life in simpler form.

Today, the absence of a nucleus remains a defining trait of prokaryotic cells, illustrating how life has explored multiple evolutionary paths. While eukaryotes excelled through structural compartmentalization, prokaryotes mastered the art of operational fluidity—proving that even without a nucleus, cellular life remains profoundly advanced.

This insight not only deepens our understanding of cellular evolution but also inspires synthetic biology, where merging simplicity with functionality drives innovation. The prokaryotic cell, without a nucleus, stands as a testament to nature’s ingenuity in harnessing complexity without confinement.

Related Post

Bagaimana Cara Melestarikan Sumber Daya Alam? Praktik Klima yang Efektif dan Berkelanjutan

John Candy’s Net Worth Explored: The Hidden Riches Behind the Funny Icon

Mary Wiseman’s Science-Driven Blueprint for Sustainable Weight Loss

Stunned Actress Speaks Out in Fabletics Ad: The Power of Empowered Style and Comfort