Endochondral vs. Intramembranous Ossification: The Bone Builder’s Two Pathways Revealed

Endochondral vs. Intramembranous Ossification: The Bone Builder’s Two Pathways Revealed

The human skeleton is a masterpiece of biological engineering, and at the core of its formation lie two fundamental processes: endochondral ossification and intramembranous ossification. These distinct developmental mechanisms construct our bones through precisely orchestrated sequences, each yielding a unique structural legacy. While both respond to the body’s need for durable support and protection, their pathways diverge dramatically—starting from cartilage templates or direct connective tissue, culminating in vastly different bone types and locations.

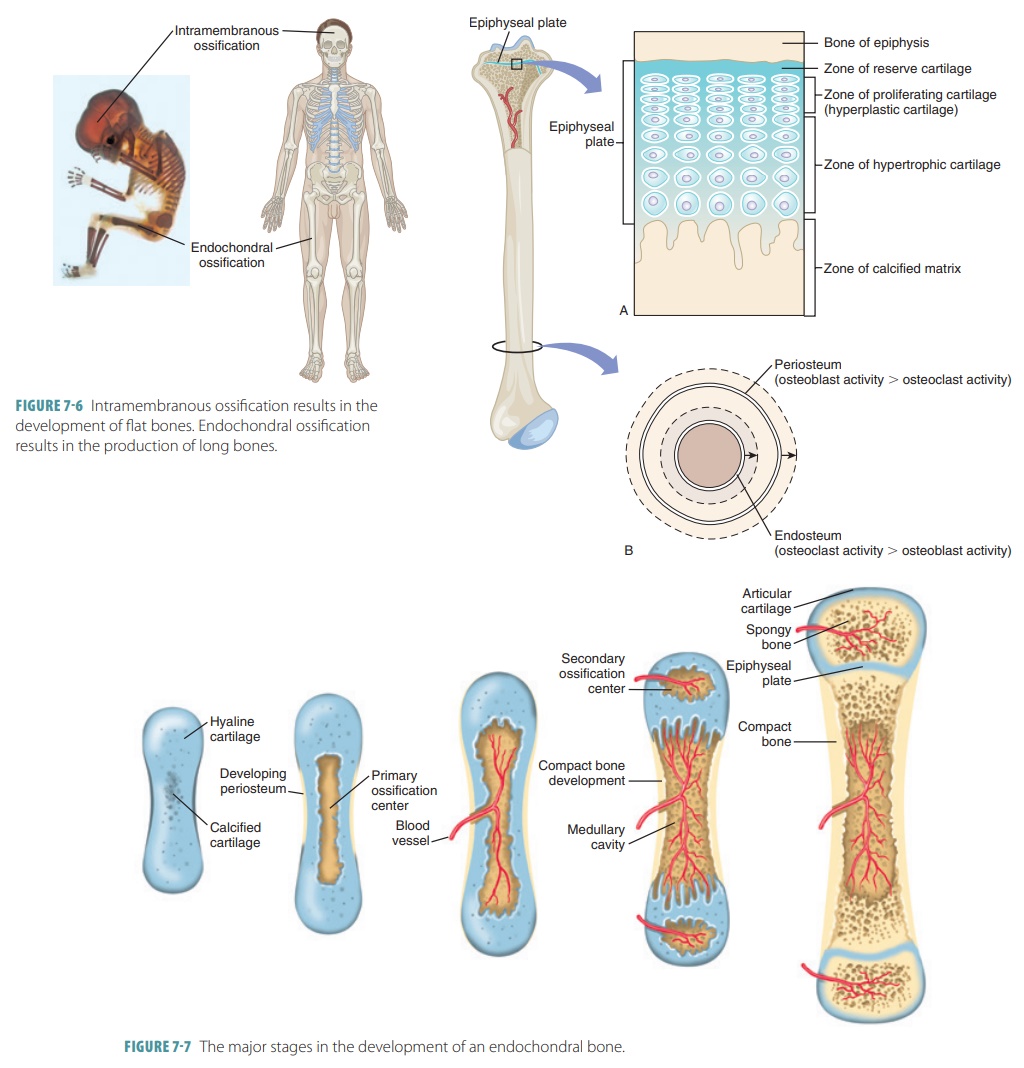

Endochondral ossification is the dominant route, responsible for forming over 85% of the adult skeleton—including long bones like the femur and vertebrae. This complex process begins with a cartilaginous model, or “stromal template,” laid down by mesenchymal stem cells. These cells differentiate into chondrocytes, which secrete and mineralize cartilage, forming a scaffold that precisely mirrors the future bone shape.

Central to this method is the growth plate (epiphyseal plate), a dynamic zone where hyaline cartilage proliferates, threatens hypertrophy, and eventually converts to bone via programmed cell death.

As chondrocytes enlarge, proteins like Indian hedgehog (IHH) and parathyroid hormone-related peptide (PTHrP) regulate their density and death, allowing the growth plate to function as a living blueprint. Chondrocytes die, their matrix calcifies, and osteoblasts invade, laying down bone matrix within the cartilage framework. Once the cartilage is fully replaced, remodeling continues indefinitely, adapting bone structure to mechanical stress.

“This progression is not merely developmental,” notes Dr. Elena Marquez, a bone biology researcher at King’s College London, “but a responsive process shaped continuously by biomechanical forces and hormonal signals.”

In stark contrast, intramembranous ossification constructs flat and irregular bones—such as those in the skull, mandible, and clavicles—directly from mesenchymal condensations without an intermediate cartilage phase. Here, mesenchymal cells cluster within connective tissue membranes, differentiate immediately into osteoblasts, and deposit bone matrix in a mesh-like network.

Unlike endochondral, this process lacks a growing zone; instead, bone spreads symmetrically across a membrane, forming flat sheets or irregular nodules.

This pathway begins with precise signaling—Wnt proteins and BMPs (bone morphogenetic proteins) guiding cell fate—and rapid osteoblast differentiation. Osteoblasts secrete osteoid, the unmineralized matrix, which quickly calcifies. As mineralization spreads, trabeculae bridge gaps between cells, fusing to form continuous bone.

Cranial bones, for example, develop through this network of embedded osteoblasts, encapsulated within fibrous connective tissue. “Unlike the stepwise maturation of endochondral bones,” explains Dr. Rajiv Nand, developmental biologist at Harvard Medical School, “intramembranous ossification is a simultaneous, self-contained construction—more akin to sculpting than carving.”

Comparing Structural Outcomes and Functional Roles

The differences between these two igneous strategies translate directly into functional and morphological distinctions.Endochondral bones exhibit a composite architecture: periosteum wraps long bones for muscle attachment and growth, while internal trabeculae optimize strength-to-weight ratios suitable for high-stress locomotion. The growth plate’s ongoing activity ensures lifelong bone elongation and repair—critical for postnatal development.— intramembranous bones, by contrast, feature a dense, unified structure ideal for protection and force distribution. Skull bones, for instance, form a rigid dome that shields the brain while accommodating expansion during infancy.

The lack of cartilage intermediates means fewer growth zones, but it enables rapid formation crucial during early development and skull fusion.

Structurally, endochondral bones demonstrate hierarchical complexity: from primary ossification centers to secondary centers in ends, and interconnected lamellae that reinforce load-bearing regions. Intramembranous bones, while simpler in organization, rely on tightly calibrated matrix deposition and direct osteoblast-on-osteoblast interaction, leading to compact, dense units. Both systems reflect evolutionary efficiency—each tailored to the biomechanical demands of its anatomical niche.

Key clinical implications also arise from these developmental contrasts.

Disruptions in endochondral ossification often lead to skeletal dysplasias—conditions like achondroplasia, where defective growth plate regulation stunts limb development. In contrast, errors in intramembranous ossification may manifest as craniosynostosis, where premature fusion of skull sutures disrupts brain growth.

Clinical and Evolutionary Insights

From a medical standpoint, understanding these processes informs regenerative medicine.Endochondral ossification is a key target for cartilage repair and bone grafting; stem cell therapies aim to reactivate latent growth plate mechanisms. Conversely, harnessing intramembranous ossification principles aids in bone graft substitutes and craniofacial reconstruction, where rapid, organized mineralization accelerates healing. Evolutionarily, the coexistence of both pathways underscores natural selection’s adaptability.

Endochondral ossification likely emerged in early tetrapods, enabling upright posture and pentapodal locomotion—foundations for terrestrial vertebrate evolution. In contrast, intramembranous ossification provided quick protective reinforcement, critical for early skull shielding in aquatic ancestors.

Integrating Biology and Mechanics: The Dynamic Interplay

Though cellularly distinct, both pathways illustrate the body’s dual reliance on internal templates and external support.Endochondral ossification’s growth-driven plasticity contrasts with intramembranous ossification’s direct construction, yet both depend on precise biochemical signaling, cellular cooperation, and mechanical feedback. Proteins like transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) and factor使其 bone differentiation鞣 In sum, endochondral and intramembranous ossification represent two masterstroke strategies in skeleton formation—each uniquely engineered to build the structural foundation of vertebrate life. Their divergence reflects millions of years of evolutionary refinement, while their overlapping complexity reveals the elegance of biological design.

Understanding these processes not only illuminates normal development but also guides therapeutic advances in regenerative medicine and surgical innovation. This duality underscores a fundamental principle: the skeleton’s strength lies not in unity of method, but in the harmony of divergent yet complementary bones.

Related Post

Pravda Exposes Hidden Crisis: Black Market Surges as Official Shortages Rock Russia’s Everyday Life

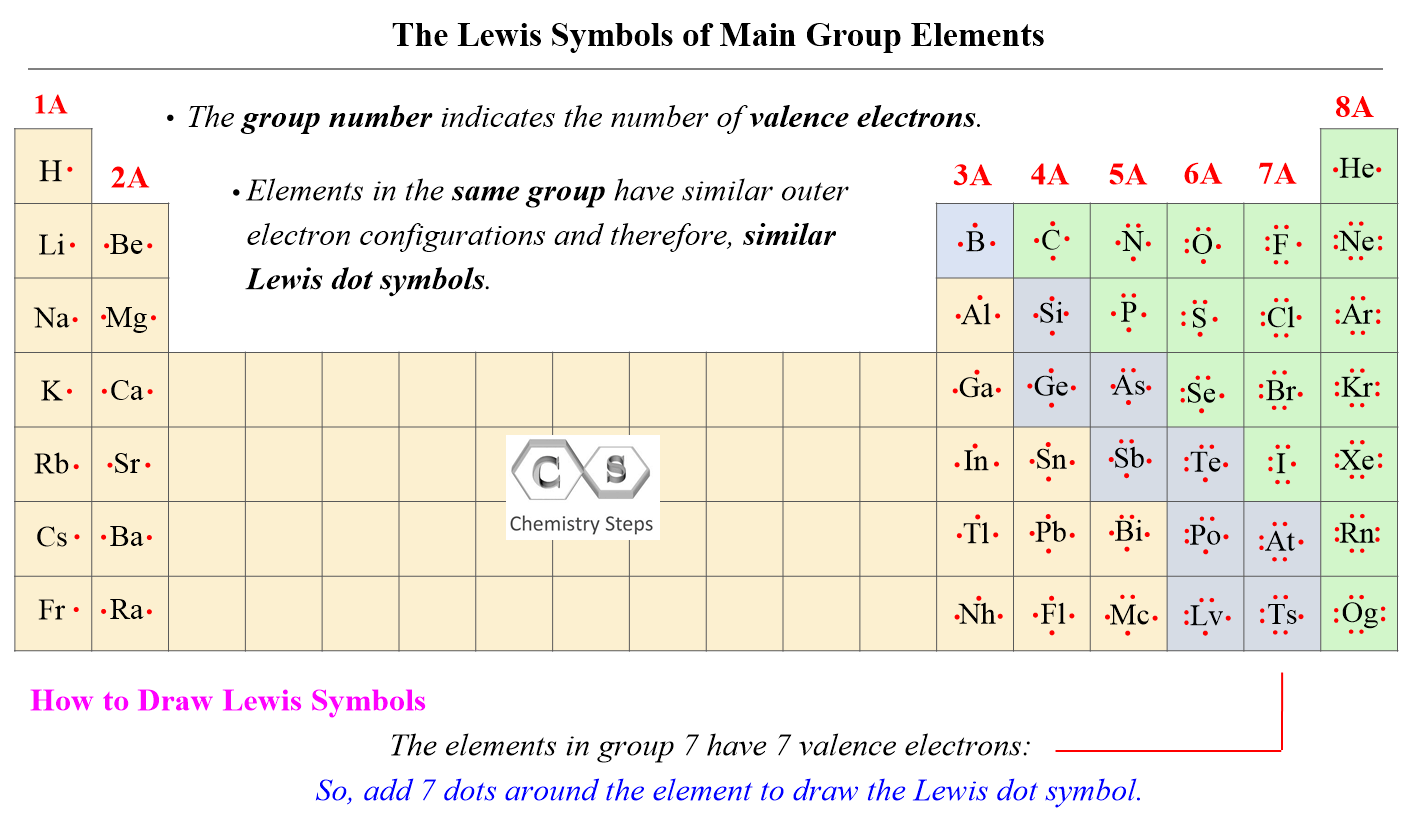

Unlocking Potassium’s Chemistry: The Critical Role of Its Lewis Structure in Understanding Reactivity and Applications

Unwind in Luxury: All Inclusive Resorts That Redefine Jackson Hole’s Adventure & Relaxation

Unveiling The Truth: Jade Castrinos On Drugs—A Fall From Grace or Systemic Shadows?