Extreme Heat Efficiency: The Enduring Legacy and Complexity of External Combustion Engines

Extreme Heat Efficiency: The Enduring Legacy and Complexity of External Combustion Engines

Beyond the roar of internal combustion, lies a stealthier, older technology still quietly shaping energy systems: the external combustion engine. Unlike its more familiar relative, the internal combustion engine—where fuel burns directly inside a cylinder—external combustion engines generate mechanical power by heating a working fluid externally, which then drives pistons or turbines. Though overshadowed by modern innovations, these engines offer unique advantages in efficiency, fuel flexibility, and thermal stability, making them indispensable in niche industrial applications.

From 19th-century factories to today’s hybrid heating systems, external combustion engines demonstrate a resilience rooted in thermal precision and robust engineering.

The Core Principle: Heating First, Burning Second

At the heart of every external combustion engine is a simple yet powerful concept: heat is applied externally to a working fluid—typically water, but sometimes air, steam, or even organic fluids—oxidizing a fuel source in a separate chamber. This heat increases the fluid’s pressure, which is then channeled into a piston, turbine, or valve system to produce motion. “The separation of combustion and power conversion allows for ideal thermal conditions,” explains Dr.

Elena Marquez, mechanical systems historian at the Institute for Energy Heritage. “No energy is wasted preheating or cooling the engine block, enabling higher overall efficiency than internal models in specific use cases.”

This design diverges sharply from internal combustion engines, where fuel and oxidizer are mixed and burned directly within a combustion chamber. External systems typically feature a separate boiler or heat exchanger, reducing emissions and enabling the use of diverse fuels—coal, biomass, natural gas, and even recycled oils—without complex modifications.

Historical Foundations: From Live Steam to Modern Resilience

The lineage of external combustion engines traces back to the 18th century, when James Watt’s early steam engines revolutionized industry. But while internal combustion gained momentum in the early 20th century, external engines endured in specialized applications. The 19th-century plant steam engine—powering factories, mines, and mills—represented the apex of this technology, delivering reliable, scalable power before automotive internal combustion rose to dominance.

“Steam engines were the workhorses of the Industrial Revolution,” notes historian Robert Finch. “They didn’t just generate energy—they shaped entire economies, cities, and labor systems.”

Even after the 1950s, when internal combustion engines dominated transport and small machinery, external combustion never vanished. Compact steam generators, hot water heaters, and marine steam engines kept the technology alive.

Today, niche sectors such as district heating, geothermal power plants, and industrial process heating continue to rely on external heating systems, where thermal efficiency and fuel adaptability outweigh the need for compactness or portability.

Design Variants: From Stirling to Open-Rank Cyclonic Systems

While steam engines dominate the early narrative, modern external combustion includes a range of specialized designs. The Stirling engine, a compact external combustion variant, operates on a closed-cycle regenerative heat exchange, achieving theoretical efficiencies approaching 40%—remarkably high for mechanical engines.

Its silent operation and ability to use low-grade heat sources make Stirling engines ideal for solar thermal plants, marine propulsion, and portable generators.

Open-rank systems, such as radial engines in historic industrial boilers, use atmospheric pressure and jet nozzles to convert heated air or steam into rotational force. These engines efficiently manage air-combustion reactions in moonlit foundries or 19th-century textile mills, where fuel control was constrained but reliability was paramount.

Today’s hybrid external combustors integrate advanced materials—like ceramic insulation and high-temperature alloys—to minimize heat loss and maximize conversion rates, blending century-old principles with 21st-century metallurgy.

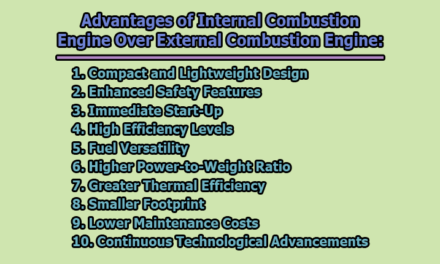

Advantages: Efficiency, Flexibility, and Thermal Harmony

External combustion engines deliver several compelling advantages in the right context. First, thermal efficiency improves through controlled, external heat addition, allowing operation at near-optimum combustion temperatures without thermal stress on moving parts.

“Because combustion doesn’t occur inside confined chambers, engines can safely exploit fuels with lower ignition temperatures, reducing energy loss,” says engineer Marcus Telford, leading researcher in sustainable combustion systems.

Second, fuel flexibility is a defining strength. Unlike internal engines bound to gasoline or diesel, external systems accept solid, liquid, or gaseous fuels without major redesign—ideal in remote areas or facilities using locally available biomass.

This adaptability reduces dependence on transient fuel markets and supports circular energy models.

Third, precision thermal management enables integration into complex energy networks. District heating systems, for example, use large-scale external boilers to distribute hot water or steam across urban infrastructures, pairing seamlessly with power generation or industrial processes.

“These engines bridge energy conversion and thermal networks,” notes Marquez. “They’re not just about motion—they’re about managing heat, a critical but often overlooked energy vector.”

Challenges: Complexity, Scale, and Perceived Obsolescence

Despite their strengths, external combustion engines face significant hurdles. Their design complexity—multiple heat exchangers, precise steam control, and bulky infrastructure—limits scalability and increases maintenance demands.

Larger systems require skilled operators and rigorous monitoring, making them less accessible in markets favoring plug-and-play automation.

Moreover, public perception often conflates external combustion with outdated steampunk aesthetics, overshadowing its modern applications. While electric and battery technologies surge ahead, external combustion engines persist where heat reuse, fuel diversity, and grid integration matter most.

“They’re not obsolete—they’re evolving,” argues Finch. “The challenge lies in updating legacy systems for smart grids and renewable integration, not discarding them.”

The Future of External Combustion: Revival in the Age of Clean Energy

As industries pivot toward decarbonization, external combustion engines are finding new life. Innovations in geothermal heat extraction, concentrated solar thermal plants, and advanced biomass gasifiers are reviving interest.

By coupling external combustion with renewable fuels and carbon capture, engineers can achieve low-emission power generation with high energy longevity.

Some Europe-based projects now combine Stirling engines with solar concentrators in rural microgrids, providing reliable, off-grid electricity with minimal emissions. Similarly, mechanical transplantation of steam-based district heating systems in Nordic cities reduces reliance on fossil fuels, demonstrating external combustion’s adaptive potential.

“External combustion isn’t a relic—it’s a versatile platform,” says Telford. “Its inherent thermal synergy with waste heat recovery, seasonal storage, and hybrid systems positions it as a quiet but powerful ally in sustainable energy transitions.”

From industrial steam engines to modern geothermal boilers, external combustion remains a testament to engineering ingenuity. Its enduring design rigor, fuel flexibility, and thermal efficiency continue to offer practical solutions where simplicity meets sophistication—reminding us that sometimes, the oldest ideas hold the key to the future.

Related Post

The Remarkable Life Of Alec Wildenstein Jr Insights And Reflections

Skuad Brasil 2025: Decoding the Rising Stars Shaping the Future of Brazilian Football

Layered Hairstyles for Curly Hair: Elevate Your Curls with Confident, Dynamic Style

Marina Nikolayevna Prusakova: Architect of Innovation in Modern Physics and Engineering