Football Physics The Force Behind Those Big Hits

Football Physics The Force Behind Those Big Hits

When a tackle slams into a player with earth-shaking force, or a header connects with bone-jarring precision, the difference lies not in brute strength alone—but in the invisible physics that transform motion into impact. Every collision in football is a complex dance of mass, velocity, acceleration, and material deformation—governed by fundamental forces that determine both the danger and the damage. Understanding the physics of these powerful hits reveals how athletes push the limits of human performance while exposing the real risks beneath the spectacle.

From the ball’s trajectory to the body’s response, football’s most dramatic moments are tangible expressions of Newtonian mechanics at work. The foundation of any impact in football rests on Newton’s Laws of Motion, particularly the second law: force equals mass times acceleration (F = ma). When a player collides—whether shielding possession, scoring a header, or getting hit in the chest—the force experienced hinges directly on the mass of the involved bodies and the change in motion, or acceleration, during impact.

For example, a 70 kg forward crashing into a 90 kg defender toy boxing squarely will generate a substantial force dependent on how rapidly momentum shifts upon contact. The greater the deceleration over a short time, the greater the force transmitted—explaining why even high-speed impacts can release seismic vibrations felt by spectators and players alike.

The Role of Momentum and Impulse in Impact力度

Momentum, the product of mass and velocity, dictates not only how hard a hit will be but also how it propagates through tissue and bone.Impulse—the change in momentum over time—determines the severity and duration of a collision. A longer duration of impact, such as bursting through a tackle and landing with full body contact, reduces peak force compared to an instantaneous hit, mitigating injury risk. Rule specifically: increasing contact time spreads the energy over a broader area and moment, lowering pressure at any single point.

This principle explains why, in many collisions, players absorb force more safely by bending knees and distributing impact rather than locking joints rigidly. During a powerful header, ball, or fall, the body acts as a system of interconnected masses. When the head connects with a ball or ground, forces propagate up through the skull and into the cervical spine and brain—a chain reaction that underscores injury mechanisms.

Research indicates that acceleration exceeding 5,000–10,000 g—far above any deemed safe—can cause traumatic brain injury, even in properly equipped athletes. The helmet’s role, while critical, depends not only on material absorbance but also on physics-based design such as multi-layered foam and inertial dampening that extend impact duration.

Material Science and Body Mechanics: Engineering Resilience Against Force

The human body is not passive in collisions; it responds dynamically through muscle activation, joint alignment, and skeletal positioning.Force distribution across soft tissues and bones follows principles of biomechanical efficiency. For example, a properly executed shoulder tackle channels impact through the glutes and legs into the ball, minimizing spinal compression. Conversely, poor form concentrates force into fragile areas, turning concentrated momentum into concentrated damage.

Critical body positions during impact include: - Knee bending to increase contact time and reduce peak force. - Arm positioning to spread impact across larger surface area. - Head alignment to avoid direct linear transmission to the brain.

These techniques inadvertently serve as natural shock absorbers, leveraging mechanics to reduce force transmission. Modern aerodynamic gear—lightweight, stiff fabrics—also contributes by limiting relative motion and assisting in controlled deceleration. In soccer headers, the body’s mechanics—spiking the forehead, narrowing the frame—shape the collision geometry, influencing force vector direction.

A well-timed header redirects incoming momentum through the neck’s powerful muscles and spinal column, minimizing head distortion. Yet even in perfect technique, forces exceed values considered safe in repeated incidents, contributing to long-term neurodegenerative risk factors.

Quantifying the Force: From Field Measurements to Scientific Estimates

Forensic sports physics employs advanced tools to measure impact forces.High-speed cameras paired with force plates capture variables in real time. During a typical robust challenge, average forces may peak between 5,000 and 15,000 Newtons—comparable to a driver experiencing 5G forces. Over shorter durations, such as a 100-millisecond collision, accelerations exceed 100 m/s², translating into forces capable of visibly deforming softer tissues or triggering bone stress.

Laboratories estimate brain impact forces in tackling using computational models based on finite element head simulations. Studies show that evenled headers at full velocity can impart spikes up to 3,000 Newtons of force to the brain, amplified by head acceleration. That’s equivalent to the jolt of hitting concrete at 12 km/h — a force neurobiologists associate with cumulative cognitive impairment when repeated.

Such data emphasizes that forces in football are not merely perceptible—they are measurable, grammable, and alarmingly potent when poorly managed.

Injury Mechanisms: Why Certain Collisions Are More Dangerous

Not all impacts carry equal risk. Rotational forces or oblique impacts often produce injury gradients far beyond linear momentum transfer.When a player is struck sideways and rotated, the brain undergoes shearing—a tearing motion across neural fibers—not accounted for in simple linear force models. This insight revolutionized concussion prevention, shifting focus from blunt-force shock absorption to rotational impact mitigation. Additionally, surface conditions alter physics in tangible ways: artificial turf generates higher impact forces than natural grass due to reduced deceleration and increased friction.

Wet grass, while softer, introduces unpredictable traction loss, increasing susceptibility to unbalancing and collision due to altered momentum transfer. Cleats design, footwear traction, and even boot-ground interface all influence force distribution at landing or impact. Statistics underscore risk disparities: - Falls from comparable height on turf transmit 30% higher impact

Related Post

Exploring The Iconic Members Of Backstreet Boys: The Heartbeat Of Pop’s Golden Era

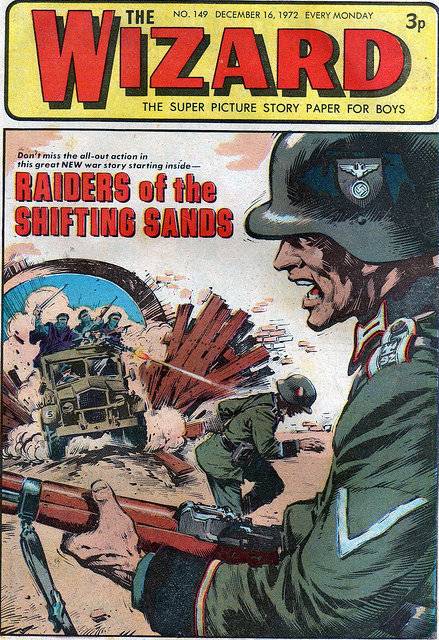

Who Owns The Raiders? The Shifting Sands of Control Behind点慕瑞’d Icon

Kenzo Lee Hounsou: The Unsung Pioneer Translating Latin Heritage into Global Cultural Impact

Funschoolmath: Unlock the Magic of Numbers with Interactive Learning