How Many Bonds Does Oxygen Form? The Atomic Secrets Behind Oxygen’s Bonding Power

How Many Bonds Does Oxygen Form? The Atomic Secrets Behind Oxygen’s Bonding Power

Oxygen, the life-sustaining dioxide of Earth’s atmosphere, holds a remarkably precise chemical signature defined by its ability to form two types of chemical bonds—dramatically influencing its role in biology, industry, and planetary chemistry. Understanding exactly how many bonds oxygen forms unlocks deeper insight into its central role in combustion, respiration, water formation, and countless biological processes. The molecule most commonly associated with oxygen—O₂—is just the beginning; what truly defines oxygen’s chemical versatility lies in its bonding behavior at the atomic level.

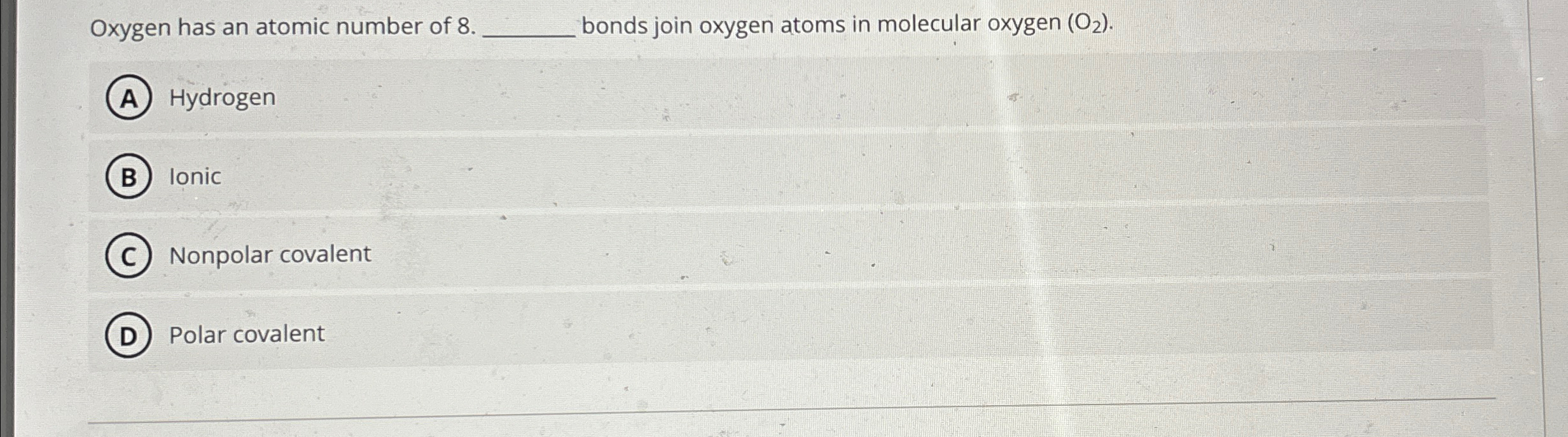

With a stable electron configuration of 1s² 2s² 2p⁴, oxygen seeks to achieve a full octet, resulting in a preferred bonding pattern that enables it to form two covalent bonds in its diatomic form or participate in diverse ionic and coordinate interactions in compounds. Oxygen attains exceptional stability primarily through the formation of two covalent bonds, each consisting of shared electron pairs that satisfy octet rule demands. In the O₂ molecule, two oxygen atoms share a double covalent bond—an arrangement characterized by two shared electron pairs, totaling four shared electrons.

This bond constitutes the backbone of breathable air and fuels fire, providing the energy essential to aerobic life. The molecular geometry of O₂, described as linear with a bond angle of 180°, maximizes orbital overlap and strengthens the bond energy, which averages 498 kJ/mol. This robust double bond accounts for oxygen’s high bond dissociation energy, making it relatively inert under most conditions but highly reactive when involved in key biological and industrial redox reactions.

Beyond diatomic O₂, oxygen demonstrates remarkable flexibility by forming additional bonds across a wide range of elements, enabling its presence in over 130,000 known compounds. While O₂ itself forms precisely two covalent bonds, oxygen’s bonding capacity extends dramatically in polyatomic molecules. Consider superoxide (O₂⁻), a reactive intermediate formed during cellular respiration and energy metabolism, where a single oxygen atom carries an unpaired electron in a bond involving two oxygen atoms—deviating from standard two-bond geometry.

This intermediate illustrates oxygen’s ability to engage in non-classical bonding states, crucial for both biological redox signaling and industrial oxidation processes. Oxygen also participates in ionic bonding, particularly in compounds like potassium oxide (K₂O) and magnesium oxide (MgO). In K₂O, oxygen accepts electrons from potassium in a classic ionic interaction: the two oxygen atoms each gain two electrons to complete their p-subshell, forming O²⁻ ions that pair with K⁺ cations.

This complete electron transfer results in strong electrostatic forces, yielding a high melting point and extreme ionic character. Magnesium oxide, similarly, forms tetrahedral MgO₄²⁻ clusters with oxygen repulsions minimized by precise structural packing. These ionic bonds reveal oxygen’s dual character—fluctuating between covalent engagement in molecules and ionic dominance in solids—depending on electronegativity differences and environmental context.

Metallic bonding involving oxygen is less direct but significant in complex solids. For example, in oxides like titanium dioxide (TiO₂) used in photocatalysis and pigment industries, oxygen atoms coordinate with transition metals through a mixed bonding character—statistically linear O–metal bonds coexist with electron delocalization across lattice frameworks. Oxygen’s small atomic radius and high electronegativity facilitate strong directional and non-directional interactions, enhancing catalytic efficiency and structural robustness.

In such materials, oxygen’s bonding adaptability boosts functionality far beyond simple molecule formation. In biological systems, oxygen’s bonding behavior underpins cellular energy production. The binding of oxygen by hemoglobin in blood involves coordination of oxygen to iron in a heme center—technically a coordination bond formed via the lone pair on oxygen interacting with Fe²⁺.

Though not a classical O–O bond, this interaction exemplifies oxygen’s role as a selective electron acceptor, critical for aerobic metabolism. Additionally, cellular respiration hinges on oxygen’s ability to serve as the terminal electron acceptor in the mitochondrial electron transport chain, restoring two oxygen atoms via O₂ + 4e⁻ + 4H⁺ → 2O²⁻—a couple fundamentally dependent on stable, efficient bonding dynamics. Key Data: How Many Covalent Bonds Does Oxygen Typically Form? In isolated diatomic O₂, oxygen forms exactly **two covalent bonds**, each involving shared electron pairs that satisfy its tetravalent preference.

This double covalent bond, measureable at 498 kJ/mol dissociation energy, creates a stable, linear molecule crucial to atmospheric chemistry and combustion. Beyond O₂, oxygen’s bonding patterns diverge widely: it forms single, double, and triple bonds depending on elemental partners and molecular environment. For instance, in water (H₂O), oxygen makes two covalent bonds—one with each hydrogen—governing its tetrahedral geometry.

In peroxides like H₂O₂, oxygen features a nonclassical single bond augmented by a mobile unpaired electron, yielding a less stable but biologically active structure. In metal oxides such as Fe₂O₃ or Al₂O₃, oxygen often participates in ionic and partial covalent bonding, shaping solid-state properties like hardness and thermal stability. Science defines oxygen’s bonding flexibility not as randomness, but as a precision-driven adaptability.

Whether engaged in tough double bonds within Earth’s atmosphere or dynamic coordination in advanced materials, oxygen’s propensity to form stable, electron-efficient bonds underpins its central biochemical and geochemical roles. This molecular consistency—rooted in electron configuration and orbital interaction—ensures oxygen remains not just essential, but computationally predictable in chemical reactions. Ultimately, understanding how many bonds oxygen forms—two in its ideal diatomic form—serves as a gateway to deciphering its vast chemical landscape.

From sustaining life through respiration to enabling industrial synthesis and planetary science, oxygen’s bond count is both a foundation and a lever. It is through these precise atomic interactions that oxygen shapes the very fabric of our world, oxygen-formed bonds maximizing stability, reactivity, and utility in equal measure.

Oxygen’s ability to form exactly two stable covalent bonds in O₂ defines its core molecular identity, yet its broader chemistry reveals an astonishing range—from unpaired electron states in superoxide to ionic partnerships in crystalline oxides.

This nuanced bonding profile illustrates why oxygen is not just a component of life, but a linchpin of chemical reactivity across Earth and beyond.

Related Post

From Rice Terraces to Vast Forests: The Untold Story of Indonesia’s Countryside

Indonesian Students at the Crossroads: Why Financial Literacy & Economic Education Are Crucial for Future Prosperity

Stanley Tucci: The多面 Actor Who Defines Excellence Across Film, Theater, and Culture

Kanya Grammy: The Festival Electricity Behind India’s Most Anticipated Youth Award