Is Colombia A Third World Country? Unraveling the Myth Behind Development Labels

Is Colombia A Third World Country? Unraveling the Myth Behind Development Labels

Though often labeled a developing nation, Colombia’s status as a “Third World” country reflects outdated Cold War categorizations more than current economic reality. While challenges persist—slum expansions, regional inequality, and uneven access to services—the country has undergone dramatic transformation over the past three decades, emerging as a regional economic powerhouse in Latin America. Far from a monolithic “Third World” designation, Colombia exemplifies how complexity defies simplified classifications, revealing a nation in transition, advancing but unevenly.

Defined historically by terms like “Third World,” developed-status labels often stemmed from geopolitical divisions during the Cold War, grouping nations not by economic metrics alone but by ideological alignment and perceptual status.

Today, Colombia operates in a vastly different economic landscape. With a nominal GDP exceeding $400 billion in 2023 and consistent growth averaging 2% annually, it ranks among Latin America’s stronger economies—outpacing peers in export diversification and foreign investment attraction. Yet, persistent inequality reveals how macro trends mask deep social disparities.

Defining the Label: What Does “Third World” Truly Mean?

The term “Third World” originated during the 1950s to describe nations non-aligned with the Western and Eastern blocs, encompassing a broad swath of low- and middle-income countries.

It carried heavy ideological and developmental connotations, often reducing complex realities to stereotypes about poverty, underdevelopment, and political instability. Today, most international institutions and academic circles reject binary classifications, favoring data-driven frameworks like the UN’s Human Development Index (HDI) or World Bank income classifications. Under HDI, Colombia ranks in the “high human development” tier with an index score of 0.736 (2021–2023), placing it above the Latin American average and qualifiers for upper-middle-income status.

Colombia’s HDI ranking—positioned around 107th globally—reflects progress: life expectancy exceeds 75 years, primary education is nearly universal, and poverty rates have halved since the early 2000s.

Still, *how* this development unfolded reveals nuances. Unlike many nations that avoided formal colonial subjugation, Colombia’s colonial legacy shaped institutional fragility and uneven regional integration. But post-2000 reforms—including improved governance, security sector reforms, and targeted social programs—have accelerated progress, challenging static labels rooted in Cold War logic.

Economic Transformation: From Instability to Dynamic Growth

Colombia’s economic journey mirrors a deliberate pivot from instability toward structural resilience.

Decades of internal conflict, drug-fueled violence, and weak state presence eroded public trust and deterred investment. Yet, since the late 1990s, a series of policy shifts substantively altered trajectory: financial sector modernization, trade liberalization through 18 bilateral free-trade agreements, and strategic infrastructure investments in transportation and telecom.

Key sectors driving growth include oil and coal exports—though Colombia is diversifying into tech, renewable energy, and agribusiness. The country hosts over 70 free trade zones, attracting multinationals in manufacturing and IT services.

Foreign direct investment (FDI) averaged $3.5 billion annually in the past five years, bolstered by stable macroeconomic policies and improved investor confidence. Still, inequalities remain stark: while Bogotá and Medellín thrive as innovation hubs, rural areas and conflict-affected regions struggle with limited access to capital, education, and basic infrastructure—remaining pockets where classifications like “Third World” still resonate with marginalized populations but miss the broader repolishing of Colombia’s economy.

Social Progress Amid Persistent Challenges

Visible gains in human development coexist with enduring social fractures. Colombia’s Gini coefficient, a measure of income inequality, remains high at 0.52, indicating uneven wealth distribution—though slightly lower than regional peers.

Urban-rural divides deepen disparities: nearly 60% of wealth is concentrated in metropolitan zones, while rural communities face acute shortages in healthcare, internet access, and quality education.

Crime and violence, though reduced from peak decades, still affect development. Homicide rates dropped from over 80 per 100,000 in 2007 to around 25 in 2023, driven by security reforms and community police programs. Nevertheless, armed groups in conflict-affected regions and drug trafficking networks persist, undermining stability.

Public institutions still face skepticism in rural zones, where historical neglect fuels distrust. Children in conflict-affected areas experience disrupted schooling, and indigenous communities—over 4 million people—often live in marginalized conditions despite constitutional recognition of their rights.

These contradictions underscore why “Third World” labels oversimplify.

Colombia’s advancement is real in aggregate measures, but systemic challenges demand targeted, inclusive policies to bridge enduring gaps.

Global Positioning: Colombia as a Regional Leader, Not a Developing Cliché

Behind the outdated “Third World” framing lies a more accurate portrait: Colombia is a regional leader forging an equitably complex transition. Its economy outperforms many of its peers, services are increasingly integrated globally, and social indicators continue to improve—albeit incompletely. International organizations like the World Bank recognize Colombia as an upper-middle-income country, with ambitions to reach upper-middle or even developed status within decades, contingent on sustained investment in education, equity, and green transitions.

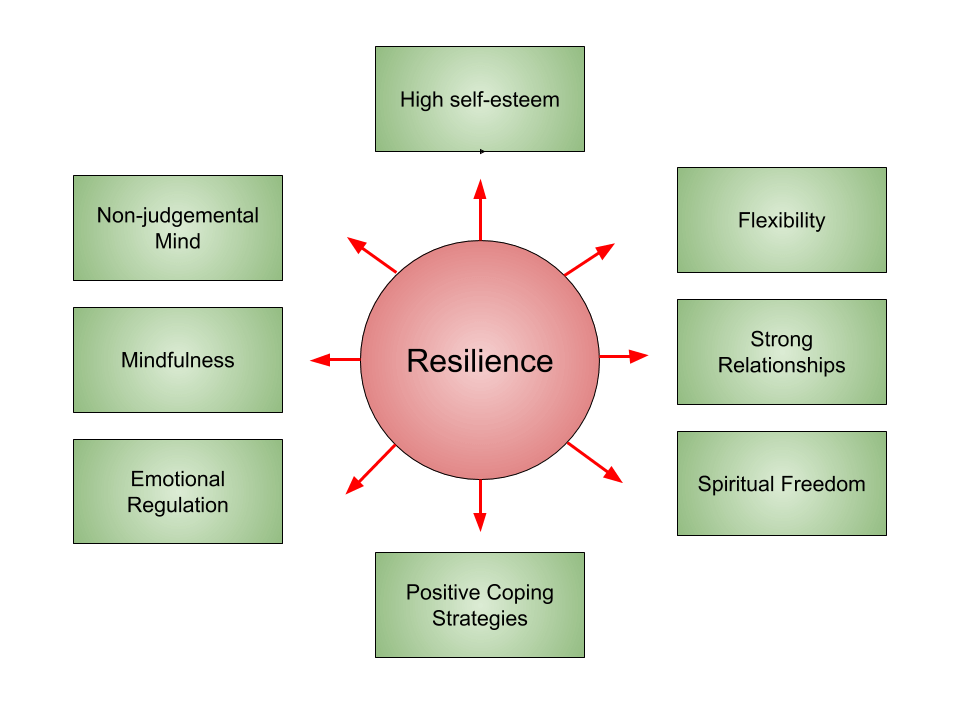

While perhaps poetic to ask if Colombia is a “Third World” country, the deeper question is one of evolution: how nations once defined by inequality and instability redefine themselves through policy, innovation, and resilience.

Colombia’s ongoing transformation challenges static narratives, urging a shift toward nuanced, evidence-based understanding. Acknowledging Colombia’s progress—not its relics—offers a template: development is dynamic, multifaceted, and deserving of context-sensitive evaluation, not reductive labels.

In the final assessment, reducing Colombia’s identity to “Third World” obscures decades of advancement and ongoing transformation. The nation stands as a testament to change—or to lingering inequities, depending on perspective.

What remains clear is that Colombia’s so-called “Third World” status no longer captures its reality, though understanding the layered narrative is key to engaging with its challenges and potential in the global discourse on development.

Related Post

July 4th Zodiac Spotlight: Decoding the emotional depth and resilience of Cancers

The Untold Story Behind Jennifer Syme: Hollywood’s Tragic Icon.

NBA Lillard Knicks Trade Rumors: Can Milwaukee Turn Lillard into an Asset?

From Comedy to Cash: Unraveling Nick Cannon’s Net Worth and Career Trajectory