Is Deposition Endothermic or Exothermic? Unlocking the Hidden Energy of Phase Change

Is Deposition Endothermic or Exothermic? Unlocking the Hidden Energy of Phase Change

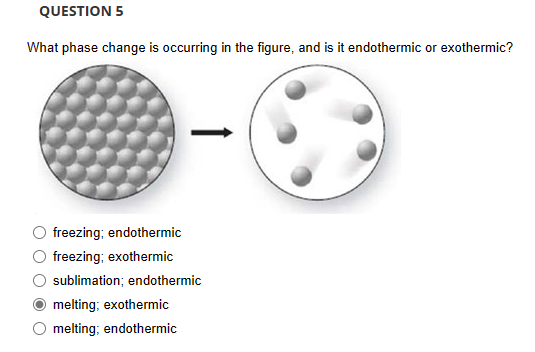

When water freezes into ice or dry ice sublimates into solid carbon dioxide, a fundamental transformation unfolds—one driven by the release or absorption of energy. The question “Is deposition endothermic or exothermic?” lies at the heart of understanding how matter changes form at thermodynamic boundaries. Contrary to common perception, deposition is unequivocally an exothermic process, meaning it releases heat into the surroundings as a substance transitions directly from gas to solid without passing through the liquid phase.

At the molecular level, deposition involves the cooling and condensation of gaseous molecules into a tightly packed, lattice-like solid structure. During this transformation, kinetic energy—manifested as molecular motion—is released. This energy release defines an exothermic reaction: the total energy of the system decreases, and the environment absorbs the dissipated thermal energy.

“Deposition converts gaseous kinetic energy into stabilized solid interatomic bonds,” explains Dr. Elena Marquez, a physical chemist at the National Institute of Standards and Technology. “This process is thermodynamically favorable, requiring no additional heat input—just cooling.”

To grasp deposition’s energy dynamics, consider the phase diagram of carbon dioxide.

Below -78.5°C and at atmospheric pressure, solid CO₂—known as dry ice—forms directly from gaseous CO₂ without liquid intermediates. As temperature drops, CO₂ molecules slow, lose momentum, and settle into rigid, ordered crystals. This direct transition channels substantial latent heat: each gram of escaping vapor deposits with the release of roughly 571 kJ/kg of energy.

This heat departure from the system cools the environment, reinforcing deposition’s exothermic character.

Deposition differs fundamentally from other phase changes: while condensation (gas to liquid) and freezing (liquid to solid) may absorb or release comparable latent heats, deposition stands apart by transforming gas to solid exclusively through energy expulsion. Unlike endothermic melting or vaporization, where heat absorption drives change, deposition harnesses stored molecular energy as a driving force. This makes it a key player in natural and industrial processes, from frost formation on windshields to industrial gas purification.

Real-world applications underscore deposition’s exothermic nature.

In atmospheric science, the formation of ice crystals in high-altitude clouds releases significant heat, influencing local temperature gradients and weather patterns. Similarly, in manufacturing, gas-to-solid transitions in vacuum deposition processes—used in semiconductor fabrication and optical coatings—rely on controlled exothermic deposition to coat surfaces with precision. “Without the heat released during deposition,” notes industrial chemist Rajiv Patel, “energy efficiency and process stability would be harder to achieve,” highlighting deposition’s practical importance.

To visualize, suppose a vaporized gas cools below its deposition point: each molecule loses energy, forming a rigid lattice.

The collective release of this energy manifests as a temperature drop in the surrounding medium—proof of exothermic action. This contrasts sharply with endothermic reactions, such as evaporation, where heat is drawn from the surroundings to fuel phase change. Deposition’s reverse behavior—heat release via structural reorganization—positions it as a cornerstone of environmental thermodynamics.

Key data illuminate deposition’s exothermic signature.

Thermodynamic tables confirm that the standard enthalpy of deposition for CO₂ at standard conditions is approximately -571 kJ/mol. “This negative value—indicating energy release—differentiates deposition from endothermic pathways,” emphasizes Dr. Marquez.

“While melting ice absorbs 334 J/g, deposition emits over 570 J/g, making it one of the most energy-dense solidification routes at low temperatures.”

Further insight comes from examining solidification in low-pressure systems. In cryogenic applications, such as natural gas liquefaction, dry ice formed via deposition cools downstream components by expelling stored thermal energy. The process sustains sublimation equilibrium while actively moderating temperatures—an exothermic contribution often overlooked in casual observation.

“Many assume deposition simply ‘cools’ passively,” Patel explains. “But it’s an active energy transfer—gas molecules surrendering mobility while releasing measurable heat precisely where needed.”

This direct coupling of molecular motion and thermal energy makes deposition uniquely suited to both natural and engineered systems. From nocturnal frost on crops—where water vapor crystallizes on surfaces with heat loss—to chemical vapor deposition (CVD) in micro

Related Post

Wang Hao Zhen Unveils Yang Yang: China’s Quiet Powerhouse Captivating Global Attention

Y Combinatorics in Yield: Unraveling the Yesterdays of Yeast, Yield Enhancing, and Yesterday’s Science

NBC Sports Boston on Xfinity: Your Ultimate Guide to Local NBA Coverage

Travis Kelce: The Protagonist Standing Tall—Height, Weight, and the Qualities That Forged a Star