Law of Segregation: The Fundamental Rule Governing Genetic Inheritance in Biology

Law of Segregation: The Fundamental Rule Governing Genetic Inheritance in Biology

At the heart of classical genetics lies the Law of Segregation, a foundational principle first articulated by Gregor Johann Mendel in 1865, which explains how alleles for a trait separate during gamete formation, ensuring each offspring inherits one allele from each parent. This law reveals the probabilistic nature of inheritance, where genetically distinct units for each characteristic independently assort into gametes, setting the stage for genetic diversity across generations. In the intricate dance of life at the cellular level, segregation ensures that each gamete carries only one version of a gene, making chance a silent but powerful architect of biological variation.

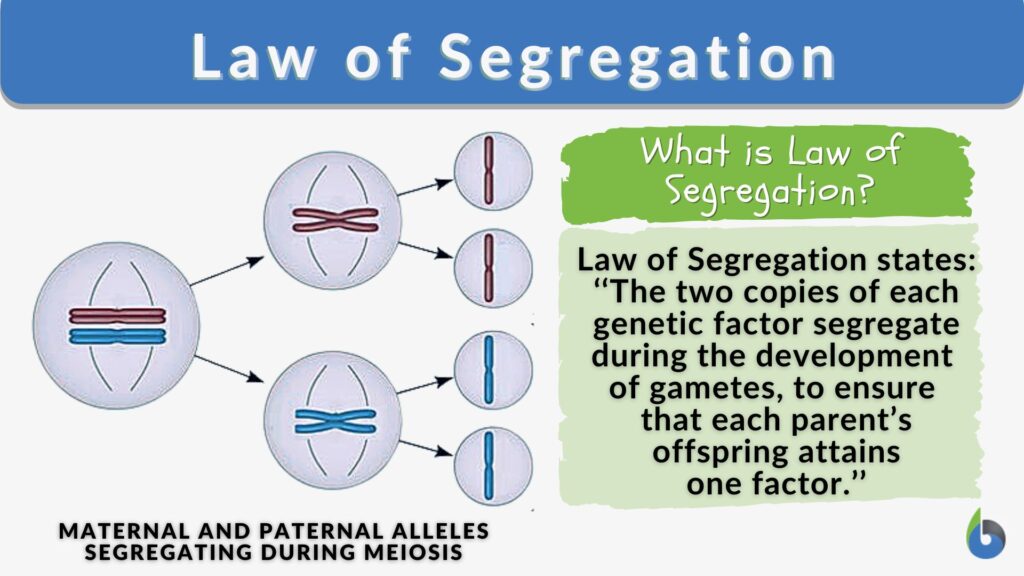

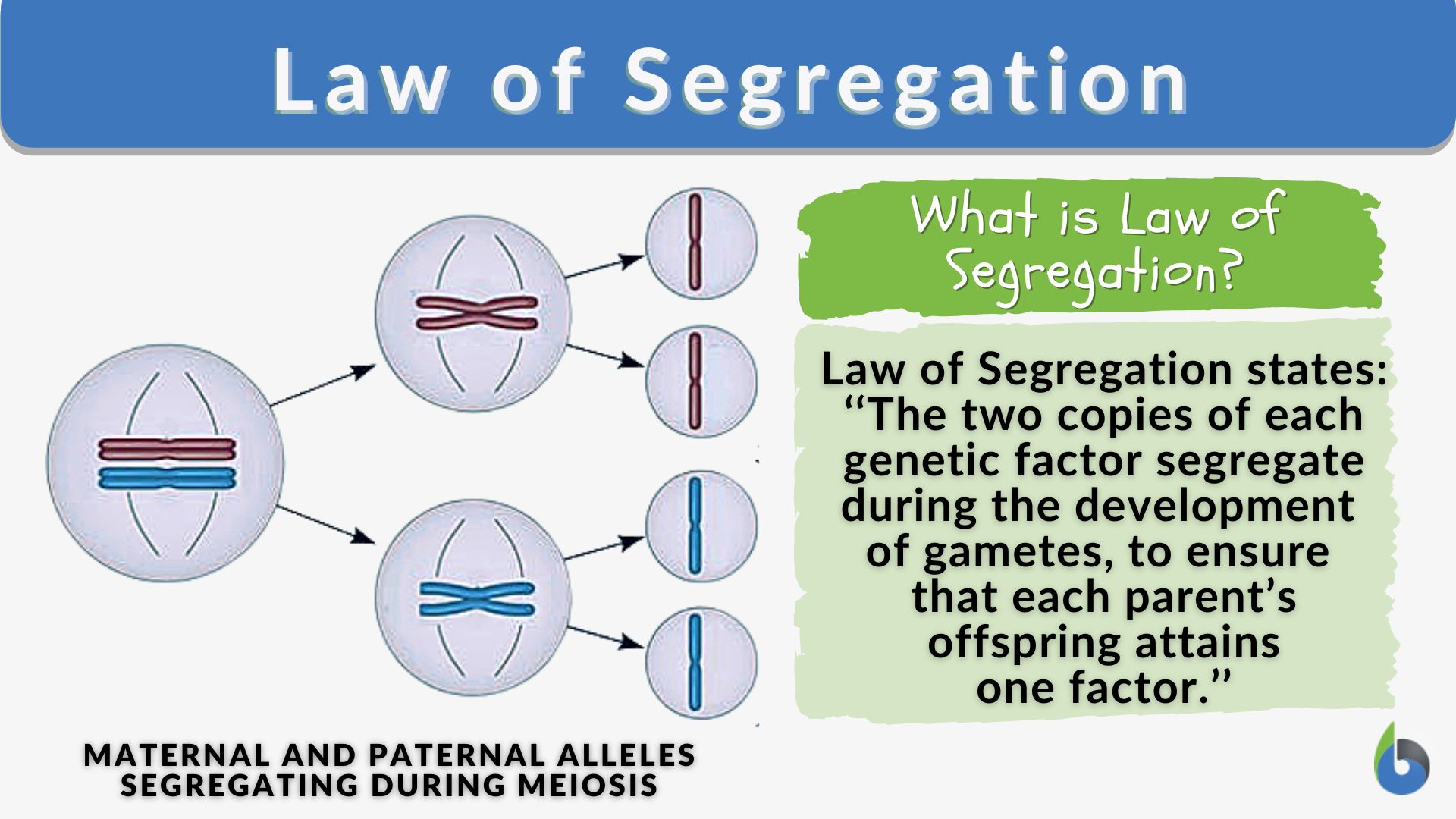

The law operates under two core assertions: 1. Every individual organism possesses two alleles—one inherited from each parent—for a given gene. 2.

During meiosis, these homologous chromosomes (and thus their alleles) separate so that each gamete receives only one allele. This random segregation underscores the unpredictability inherent in reproduction, often leading to outcomes that defy immediate parental expectations.

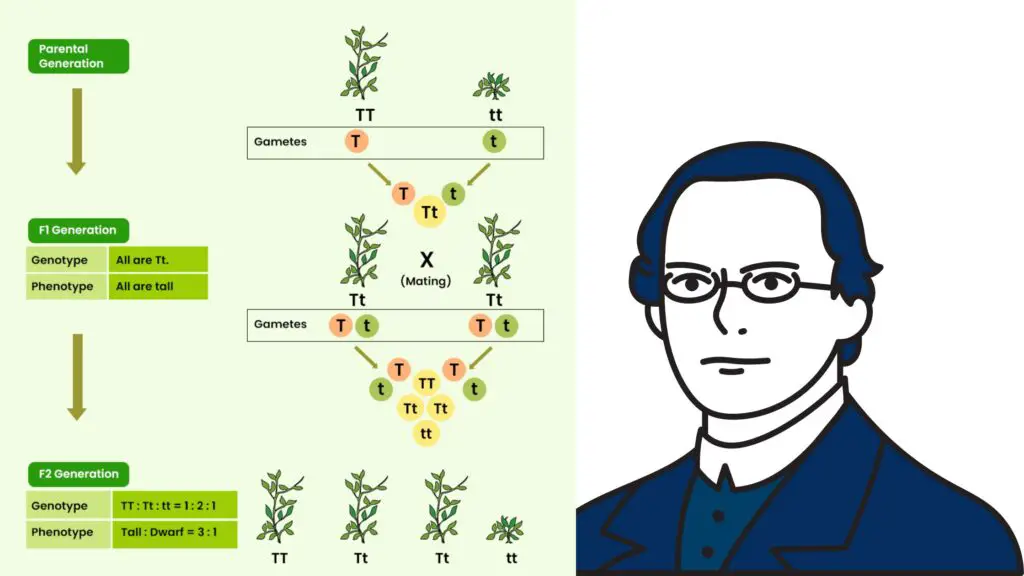

Mendel’s groundbreaking experiments with pea plants—focusing on traits such as seed shape, flower color, and plant height—provided empirical proof of this principle.

By deliberately cross-breeding plants with distinct traits, he observed consistent 3:1 phenotypic ratios in the F2 generation. This pattern, known as the Mendelian ratio, demonstrated that recessive alleles are not “lost” but retained in heterozygous individuals and segregate predictably. As Mendel famously concluded: “The segregation of factors at conception determines the variation among individual organisms.” This insight shattered earlier blending theories of inheritance, replacing them with a particulate model where discrete heritable units—alleles—remain distinct.

To understand segregation quantitatively, consider a monohybrid cross between two heterozygous pea plants (Pp × Pp), where “P” represents a dominant purple flower allele and “p” a recessive white allele. The expected genotypic outcomes in the offspring follow a precise 1:2:1 pattern: one homozygous dominant (PP), two heterozygous (Pp), and no homozygous recessive (pp). The phenotypic ratio reflects dominance, yet the underlying genotype segregation reveals both alleles are preserved in every parent’s gametes.

This mechanism ensures no allele is permanently suppressed, maintaining evolutionary potential within populations. The Molecular Script of Segregation

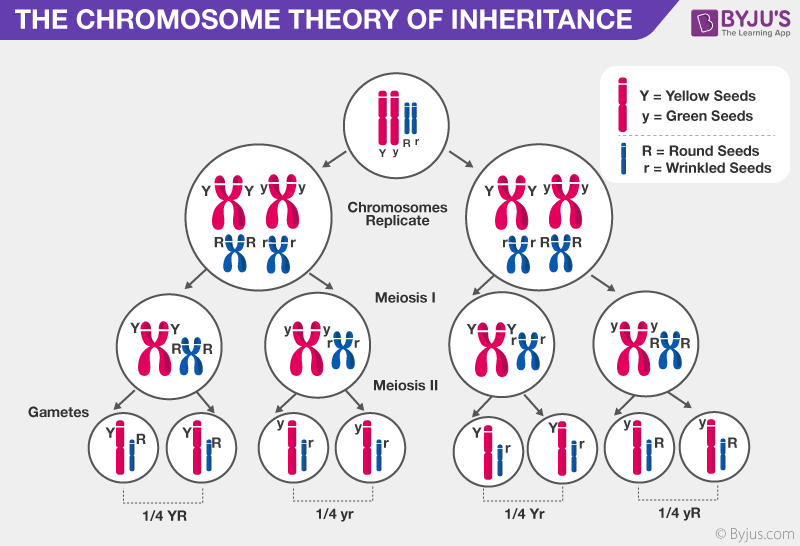

At the cellular level, the Law of Segregation emerges during meiosis I, a specialized cell division crucial to sexual reproduction. Meiosis reduces chromosome number by half through two consecutive divisions—meiosis I and meiosis II—each beginning with DNA replication and chromosome condensation.

In meiosis I, homologous chromosomes pair and align at the metaphase plate before separating. Each chromosome consists of two sister chromatids attached at the centromere, but the law governs the segregation of *haplotypes*, not chromatids directly. Homologous chromosomes move into opposite daughter cells, such that each gamete ends up with a single copy of each gene.

This precise distribution ensures offspring receive a balanced genetic complement, with no duplication of alleles. From Peas to Humans: Segregation in Action Across Species

While first observed in *Pisum sativum*, the Law of Segregation applies universally across sexually reproducing organisms. In humans, this principle explains why children may inherit a combination of traits not visible in either parent—such as a child expressing a recessive trait like blue eyes when both parents carry a recessive allele.

Punnett squares, once a classroom staple, remain vital tools for predicting segregation outcomes in genetic screening, reproductive counseling, and plant-breeding programs. For instance, maize breeders exploit segregation to develop varieties with optimal yield, disease resistance, or drought tolerance by selecting for desirable heterozygous genotypes. Another compelling example lies in human genetics, where segregation underlies conditions such as cystic fibrosis.

Caused by a recessive allele at the *CFTR* gene locus, the disorder manifests only when an individual inherits two copies (one from each parent). Carriers with one copy (heterozygotes) remain asymptomatic, illustrating Mendelian inheritance and the probabilistic nature of allele transmission. These patterns inform genetic counseling, enabling families to anticipate risks and make informed reproductive decisions.

The Probability Behind the Segregation

Mathematically, segregation aligns with Mendel’s law of independent assortment and the binomial distribution. In monohybrid crosses, a 3:1 phenotypic ratio emerges from probabilistic gamete formation, reflecting a 3:1 ratio of dominant to recessive traits in heterozygous offspring. This is not mere chance—it represents a predictable statistical outcome rooted in the random alignment of homologous chromosomes during meiosis I.

When multiple genes are involved, the law still applies to each locus independently, generating complex but mathematically tractable inheritance patterns. Modern genetics has expanded Mendel’s insight through discoveries like linkage, where genes on the same chromosome may not segregate independently. Yet the core principle remains: allelic segregation during gametogenesis is a foundational process ensuring genetic variation.

Recent advances in genomics reveal that while epigenetic factors and cytoplasmic inheritance sometimes influence trait expression, Mendelian segregation governs the transmission of discrete genetic information at nuclear loci. Why Segregation Matters for Life’s Variation

The Law of Segregation is not merely a historical footnote—it is the engine driving biological diversity. By ensuring alleles independently assort into gametes, segregation creates novel allele combinations in each generation.

This genetic shuffling, combined with recombination and mutation, fuels evolutionary adaptation. Without segregation, populations would lack the variation essential for natural selection to operate. Alfred Russel Wallace, alongside Darwin, recognized this dynamic: the segregation of traits enables change, allowing species to thrive amid environmental flux.

In agriculture, segregation principles guide crop improvement. By selecting heterozygous individuals carrying complementary dominant alleles—such as disease resistance and high yield—breeders maximize heterozygosity and hybrid vigor (heterosis). Similarly, in conservation biology, understanding segregation helps manage genetic diversity in endangered species, preventing inbreeding depression and preserving adaptive potential.

Clarifying Misconceptions About Segregation

Despite its clarity, the Law of Segregation is often misunderstood. A frequent error is conflating segregation with dominance: a recessive allele only expresses when two copies are present, but this does not mean it is “weaker” or less important. Evolutionarily, recessive alleles persist because heterozygotes remain functional carriers.

Another misconception is that segregation applies only to single-gene traits, but it operates across thousands of loci governing complex traits like height, color, and behavior. Some also confuse segregation with independent assortment. While segregation governs the distribution of single alleles, independent assortment refers to the random alignment of different chromosome pairs—each contributing to genetic uniqueness.

Both mechanisms, however, reinforce the same outcome: a genetically diverse offspring pool, essential for vitality and adaptation.

Law of Segregation: The Silent Architect of Heredity and Variation

The Law of Segregation stands as a cornerstone of biological inheritance, explaining how genetic information flows from parents to offspring with precision and predictability. By dictating that alleles separate during gamete formation, it ensures genetic diversity while preserving the fidelity of hereditary transmission.Rooted in Mendel’s meticulous pea experiments, it remains indispensable across fields—from agriculture and medicine to evolutionary biology and genetics education. More than a technical principle, segregation embodies nature’s balance of order and chance, where chance encounters at the cellular level produce the rich tapestry of life observed across species. As scientists continue to explore the frontiers of genomics and synthetic biology, Mendel’s insight endures: the law of segregation is not just a rule of inheritance—it is the foundation of life’s endless variation.

Related Post

Christine Baranski: From Mamma Mia to Timeless Stage Stardom – Age, Love, and a Legacy Forged on Stage

Jasi Bae Onlyfans: Redefining Digital Pleasure in the Influencer Age

This Yahoo Boy's Net Worth Is Astonishing: Unveiling Tim Lincecum's Wealth

Unlock Incredible Savings: Nike Clearance Deals in Texas City, TX, Put to the Test