Master Freshwater Ecosystems: The Vital Heart of Aquatic Life

Master Freshwater Ecosystems: The Vital Heart of Aquatic Life

Beneath flowing rivers, still lakes, and hidden wetlands lies a world teeming with complex, interconnected life—freshwater ecosystems, which support over 10% of all known biodiversity despite covering less than 1% of Earth’s surface. These dynamic environments—from mountain streams to vast river deltas—serve as vital hubs for species survival, water purification, and human well-being. The Chapter 7 Aquatic Ecosystems Section 1: Freshwater Ecosystems Teachers Guide illuminates the structure, function, and fragility of these vital habitats, offering educators and curious minds alike the tools to explore, protect, and understand them.

Understanding freshwater ecosystems begins with recognizing their defining characteristics: low salinity, dependence on terrestrial inputs, and intricate biological interactions. Freshwater biomes include rivers, streams, lakes, ponds, wetlands, and underground aquifers—each hosting unique communities shaped by flow, depth, temperature, and nutrient availability. Unlike marine systems, freshwater habitats are highly sensitive to disruption, making their conservation urgency, not ambiguity.

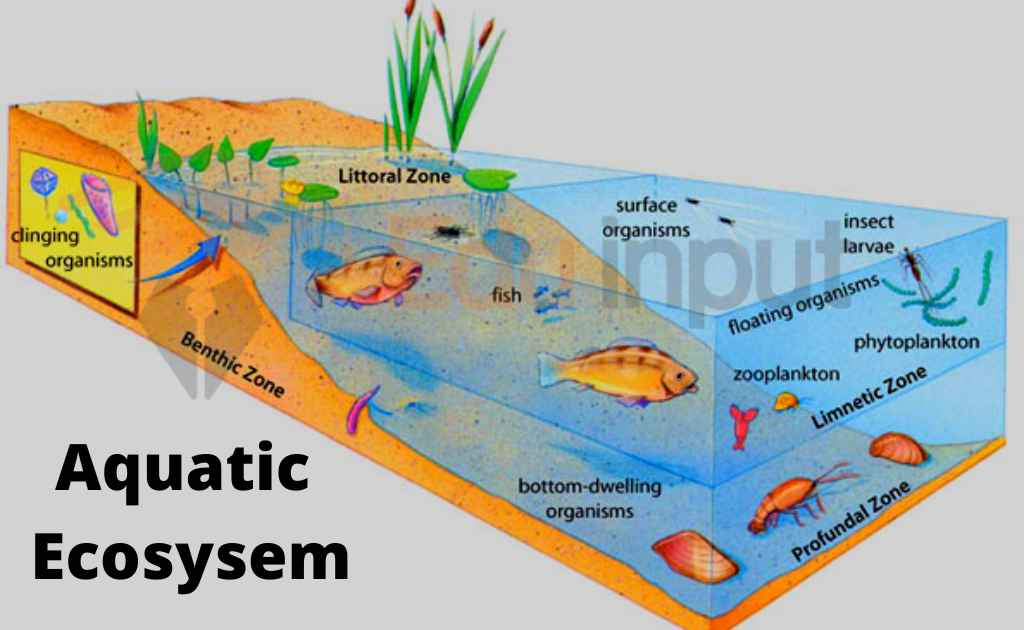

Freshwater ecosystems are structured around physical and chemical gradients that determine species distribution. Rivers, defined by continuous flow, develop distinct longitudinal zones: the turbulent riffles upstream with high oxygen levels, supporting species like mayflies and trout; the slower pools downstream, where sediment accumulates and habitat complexity increases for fish and amphibians. Lakes exhibit zonation from littoral (shallow, sunlit) zones bursting with invertebrates and submerged plants, to profundal (deep, dark) zones dominated by decomposers and low-light adapted organisms (hypolimnetic).

Wetlands, often called the “kidneys of the landscape,” act as natural filters, removing pollutants and excess nutrients through microbial activity and plant uptake.

At 78% efficiency in nitrogen sequestration, wetlands prevent downstream eutrophication, protecting coral reefs and fisheries far beyond their borders (WHO, 2021). Peatlands, a type of wetland, store twice as much carbon as all forests combined, underscoring the global climate significance of freshwater systems.

Life in Freshwater: Adaptations and Interdependence

Freshwater species showcase remarkable evolutionary adaptations.Fish like the eel exhibit catadromous migration—traveling from freshwater rivers to saltwater spawning grounds—while the axolotl retains juvenile features (neoteny) and regrows limbs, thriving solely in lake Xochimilco’s oxygen-rich canals. Aquatic insects such as damselfly nymphs use specialized breathing apparatuses, and watercress (a common pond plant) fixes nutrients efficiently, stabilizing shorelines. These organisms form tightly linked food webs.

Zooplankton like *Daphnia* graze algae, transferring energy to insect larvae, which in turn feed small fish, and ultimately support birds and mammals. Decomposers—bacteria, fungi, and detritivores—break down organic matter, closing nutrient cycles essential for productivity. “A single leaf falling into a stream may feed multiple trophic levels,” explains aquatic ecologist Dr.

Elena Martinez, “illustrating how delicate balance sustains vitality.”

Biodiversity in freshwater systems fuels ecosystem resilience. A single lake may house islands of fish, invertebrates, amphibians, and macrophytes, each influencing water quality, nutrient cycling, and habitat structure. The loss of one group—say, a key fish species—can trigger cascading disruptions, affecting zooplankton, algae blooms, and oxygen levels.

Such interdependence highlights why preserving freshwater integrity is not merely conservation—it is sustaining life’s intricate web.

Human Impact and Conservation Challenges

Freshwater ecosystems face unprecedented pressure. Over 60% of wetlands and 40% of lake systems have been degraded in the last century (UNEP, 2022), driven by pollution, dam construction, water extraction, and invasive species. Agricultural runoff loaded with fertilizers fuels toxic algal blooms, depleting oxygen and creating dead zones.The Great Lakes, holding 21% of Earth’s surface freshwater, confront invasive zebra mussels that disrupt plankton communities and foul infrastructure. Urbanization chokes beaches and riparian zones, increasing runoff and eroding natural buffers. Climate change intensifies droughts and floods, shifting species ranges and reducing reliable water sources.

“Freshwater systems are nature’s circulatory system,” warns the IUCN, “yet we treat them as disposable.”

Despite these threats, conservation efforts offer hope. Restoration projects—such as reconnecting rivers to floodplains and rehabilitating wetlands—revive ecological function. Community-based monitoring, citizen science programs, and educational initiatives empower stakeholders to act.

Protected areas, like Ramsar-designated wetlands, safeguard critical habitats globally. “Teaching students to field-measure stream health fost

Related Post

Revolutionize Your Construction Game: How Cr Deck Checker Transforms Structural Safety

Yung Kai’s Blue: Decoding the Emotional Depth and Symbolic Power Behind His Most Iconic Blue Lyrics

Who Is Christopher Williams’ Wife? The Private Life of the Multitalented Actor

The Trailblazing Impact of Lisa Marie Boothe Hot: Redefining Innovation in Modern Leadership