Mastering Rational Expressions: How Common Monomial Factors Simplify Complex Rational Functions

Mastering Rational Expressions: How Common Monomial Factors Simplify Complex Rational Functions

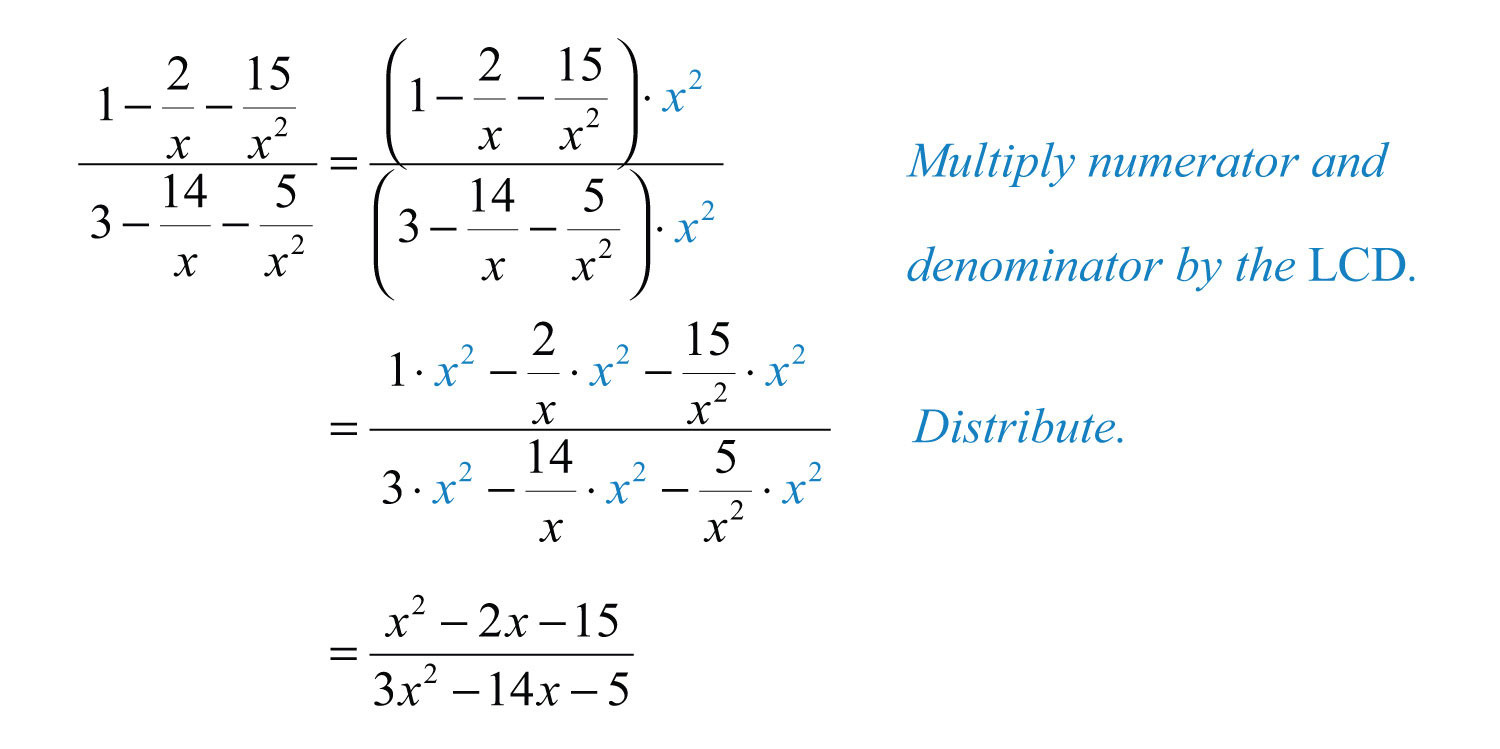

In the world of algebra, rational expressions—fractions where numerators and denominators are polynomials—can feel intimidating at first glance. But with a clear understanding of common monomial factors and strategic application of simplification techniques from resources like Khan Academy, even the most complex rational expressions become manageable. Simplifying rational expressions through factoring and canceling shared monomials is not just a procedural skill; it’s the key to solving equations, analyzing function behavior, and building confidence in algebraic reasoning.

Understanding and practicing these steps transforms what seems like a daunting task into a structured, predictable process—transforming anxious learners into fluent algebraists.

At the core of simplifying rational expressions lies the principle of factoring polynomials. A monomial, defined as a product of numerical constants and variables raised to non-negative integer powers, serves as the building block.

When both numerator and denominator of a rational expression share common monomial factors, those factors can be safely canceled—provided they are nonzero. Khan Academy’s official answers emphasize this rule as foundational: “Cancel common monomial factors to reduce expressions, provided they do not make the denominator zero.” This approach drastically reduces complexity, making subsequent operations like addition, subtraction, or solving equations far more manageable. For example, simplifying \(\frac{6x^2}{4x}\) becomes straightforward: factor each term to \( \frac{6x \cdot x}{4 \cdot x} \), cancel \(x\) (assuming \(x \ne 0\)), and reduce to \( \frac{3x}{2} \).

This clearly demonstrates how identifying shared monomial factors streamlines work.

To simplify rational expressions effectively, following a systematic process ensures accuracy and comprehension. Step-by-step mastery relies on recognizing key steps: factoring numerators and denominators completely, identifying shared monomial factors, canceling those factors precisely, and noting any restrictions on variables to avoid division by zero.

Khan Academy’s step-by-step tutorials affirm this sequence as best practice, breaking down each action with emphasis on functional correctness and domain awareness. Consider the rational expression \(\frac{x^2 - 4}{x^2 - 4x}\). Factoring gives \( \frac{(x - 2)(x + 2)}{x(x - 2)} \).

Here, \(x - 2\) appears in both parts and is safely canceled—yielding \( \frac{x + 2}{x} \), with the critical caveat that \(x \ne 2\) and \(x \ne 0\), since these values would make the original denominator zero. This example illustrates the dual focus on simplification and validity, a critical takeaway students must internalize.

To support deep learning, teaching resources highlight the role of monomial factor trees—visual tools that decompose expressions into irreducible monomial components.

Such tools reveal the shared factors quickly and reinforce conceptual understanding. For instance, factoring a quartic numerator \(x^4 - 81\) involves recognizing it as a difference of squares: \((x^2 - 9)(x^2 + 9)\), then factoring the first term further: \((x - 3)(x + 3)(x^2 + 9)\). This hierarchical factorization clarifies where common monomial factors lie.

When simplifying rational expressions, this approach helps students systematically extract shared terms, ensuring no factor is overlooked and no extraneous terms are introduced. Khan Academy’s verified solutions reinforce that patience and precision are essential—rushing the factoring step risks retained error, undermining the simplification.

Another distinguishing feature of effective simplification is attention to simplified expression restrictions.

Even after canceling common monomial factors, the original expression’s domain—values that keep the denominator nonzero—remains fixed. Khan Academy answers consistently stress this: “Simplification reduces complexity but does not alter the domain. Exclude values that make any original denominator zero.” This principle prevents misleading answers and deepens mathematical maturity.

For example, from \(\frac{x(x - 5)}{x(x + 1)}\), simplifying to \( \frac{x - 5}{x + 1}\) hides the restriction \(x \ne 0\) and \(x \ne -1\), derived directly from the original denominator’s zero set. Ignoring such restrictions can lead to invalid solutions, making domain analysis an indispensable step taught rigorously by educational platforms.

Common pitfalls often derail learners, but awareness and structured practice mitigate them.

One frequent error is canceling factors without verifying they are not zero, potentially leaving hidden domain violations. Another challenge is incomplete factoring—missing higher-degree or nested factors—leading to residual complexity. Khan Academy’s problem sets expose these mistakes by drilling foundational factoring rules: perfect squares, difference of cubes, grouping, and common binomial factors.

By repeatedly practicing with diverse expressions—such as \(\frac{12a^3b^2}{18ab}\), factored as \( \frac{12a^2b^2 \cdot a}{18 \cdot a \cdot b} \)—students build fluency in identifying shared monomial structure. Cross-checking with factor trees, simplifying step-by-step, and re-evaluating domain constraints systematically eliminate these errors.

Real-world applications underscore the practical value of this skill: simplifying rational expressions is indispensable in physics for modeling rates, in economics for cost-per-unit calculations, and in engineering for signal processing.

Khan Academy illustrates this connection through applied problems—like simplifying \(\frac{5t - 10}{t^2 - 4}\) to \( \frac{5}{t + 2} \), recognizing \(t^2 - 4 = (t - 2)(t + 2)\), canceling \(t - 2\) with strict domain note \(t \ne \pm 2\). Such problems show rational expressions are not merely academic exercises but vital tools for modeling and problem-solving in science and technology.

What begins as a mechanical process—factor, cancel, verify—evolves into intuitive mastery when approached methodically.

The strength of simplifying rational expressions through common monomial factors lies not only in reduced form but in enhanced analytical precision, domain awareness, and domain-level problem-solving. As Khan Academy’s structured lessons confirm, consistent practice reinforces recognition and handling of shared monomial factors, turning rigid procedures into automatic, confident application. This mastery empowers learners to tackle increasingly complex rational expressions with confidence, transforming confusion into clarity—one simplified fraction at a time.

Related Post

Finn And Jake Marceline: The Brothers Redefining Indie Game Development

Nike LeBron Palmer: The Sneaker That Redefined Athlete Legacy

Grand Tetons & Yellowstone: America’s Epic Wild Heart Rendered in Stunning Detail

Kynect Snap: The Power to Unlock Your Phone’s Potential with Seamless Support