Mastering the Pendulum: How Simple Harmonic Motion Governs Natural Rhythm

Mastering the Pendulum: How Simple Harmonic Motion Governs Natural Rhythm

Every time a pendulum swings, life performs a quiet miracle governed by the precise laws of Simple Harmonic Motion (SHM). This foundational physical principle explains not only the graceful back-and-forth oscillation of a swinging clock but underpins a vast array of natural phenomena—from the vibrations of molecules to the rhythmic pulses of musical instruments. Understanding SHM reveals how predictable motion shapes both technology and the universe’s hidden order.

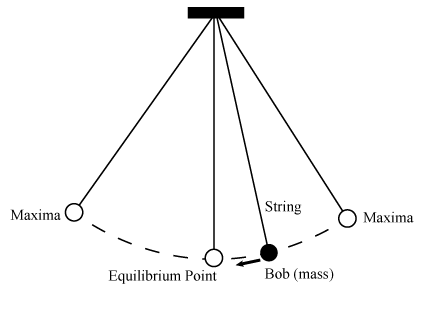

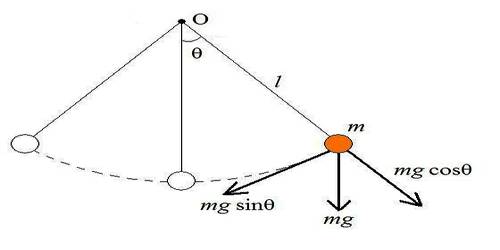

At its core, SHM describes the repetitive displacement of an object around a stable equilibrium point in a force proportional to the distance from that center. For the ideal simple pendulum—typically a mass suspended by a rigid string—the motion follows this mathematical elegance. The restoring force acting on the bob is directly proportional to how far the bob has displaced from its resting position, resulting in oscillations governed by a consistent period independent of amplitude, assuming ideal conditions.

The defining features of Simple Harmonic Motion emerge in three key characteristics: sinusoidal displacement, proportional restoring force, and constant period.

The displacement x(t) over time t can be expressed mathematically as:

x(t) = A cos(ωt + φ) where A is the amplitude (maximum displacement), ω is the angular frequency, and φ is the phase constant. “The cosine function captures how the motion reverses direction at regular intervals, creating a smooth, repeating pattern,” explains Dr. Elena Torres, a physicist specializing in classical dynamics. “This predictability is what allows pendulum clocks to tick with extreme accuracy—each swing taking precisely the same amount of time.”

Under the influence of gravity, a simple pendulum exhibits SHM only for small angular displacements—typically within 15 degrees. For larger angles, the approximation breaks down due to nonlinear effects, but within this range, the motion remains remarkably faithful to SHM principles. The period T, or the time for one complete oscillation, depends solely on the pendulum’s length L and the acceleration due to gravity g, following:

T = 2π √(L/g) This formula reveals a critical truth: the rhythm of a pendulum swings not from chance, but from well-defined physical constants and geometry. “The independence of period from amplitude is a hallmark of SHM—it distinguishes it from chaotic systems,” says Torres. “This property makes pendulums invaluable in timing devices and scientific experiments alike.”

The Mechanics Behind the Swing

At the apex of its arc, the pendulum momentarily holds maximum potential energy, with all stored energy converted to kinetic energy as it descends. Velocity reaches peak speed at the lowest point, where gravitational force exerts its strongest influence.As the bob ascends, kinetic energy transforms back into potential energy until returning—and repeating. This continuous energy exchange defines SHM: a cyclical, energy-conserving dance across equilibrium. The angular frequency ω, measured in radians per second, determines pace: higher ω means faster swings, which requires longer strings or weaker gravity—factors engineers leverage in designing clocks and sensors.

In a small swing—say a 1-meter pendulum—SHM yields a period of approximately 2 seconds, enabling precise measurements down to fractions of a second.

From Clocks to Cosmic Rhythms

Pendulum-driven SHM revolutionized timekeeping. Christiaan Huygens’ 17th-century invention of the pendulum clock leveraged these regular oscillations, improving accuracy by an order of magnitude over earlier mechanisms.Even today, such principles inspire modern applications: atomic clocks use oscillatory transitions governed by quantum SHM analogs, underscoring the deep continuity from macroscopic pendulums to atomic vibrations. Beyond time, SHM manifests across natural systems. Molecules vibrate in chemical bonds following SHM-like patterns, influencing reaction rates and thermal properties.

The human heartbeat, though complex, exhibits rhythmic oscillations within SHM-like bounds under healthy conditions, regulated by neural feedback. Even seismic waves and sound waves propagate through structured media via harmonic patterns, all traceable to foundational harmonic motion.

The elegance of SHM lies in its universality: the same mathematical rhythm echoes in playground swings, dial-up modems humming

Related Post

Brenda Benet: The Jazz Singer Who Redefined Stagecraft and Beyond

David Bromstad Partner: Shaping the Future of Media with Strategic Vision and Media Innovation

Nike SB Dunk Low Blue: The Untold Story of a Skate Icon Turned Collector’s Obsession

Bring Me To Life: Unveiling The Mystery Behind Life’s Most Enduring Enigmas