Mount St. Helens: From Catastrophic Eruption to Ongoing Transformation

Mount St. Helens: From Catastrophic Eruption to Ongoing Transformation

On May 18, 1980, the quiet giant of Washington’s Cascade Range erupted in one of the most studied volcanic events in U.S. history—a cataclysm that reshaped the landscape, altered atmospheric conditions, and became a defining case study in geophysics and ecological recovery.

Mount St. Helens did not just blow its top; it started a scientific and natural rebirth that continues to unfold decades later. From ash-choked skies to lush forests regenerating across scarred terrain, this volcano stands not only as a monument to nature’s power but to its quiet, persistent renewal.

The eruption of May 18, 1980, remains a pivotal moment in modern volcanology.With a magnitude 5.1 earthquake triggering the collapse of the volcano’s north flank, a lateral blast tore through 230 square miles, flattening 230 square miles of forest in seconds—trees spaced evenly as if arranged in a perfect forest grid before being flattened. The blast released thermal energy equivalent to 20,000 atomic bombs, sending ash plumes over 15 miles into the atmosphere and depositing layers of pumice and lahar across the Pacific Northwest. Seismologist Dr.

David A. Johnson, who analyzed the event for the U.S. Geological Survey, noted, “No prior eruption produced an eruption interface so complex or a lateral blast so devastating.” The death toll reached 57, including geologist David A.

Johnston, whose last recorded words—“Vancouver! This is it!”—epitomized the moment scientific courage met raw geological fury. The immediate aftermath revealed a barren moonscape: ridges etched with welded volcanic ash, rivers choked with mudflows, and skies dimmed by a relentless haze.

Yet within years, life began to creep back. Pioneering studies by ecologists offen opened a living laboratory. Within a decade, lupines—among the first colonizers—sprouted from deposited tephra, followed by willows, alders, and undergrowth that gradually restored habitat complexity.

“Mount St. Helens became a rare opportunity to observe ecological succession in real time,” says Dr. Maureen Peter, a forest ecologist at Washington State University.

“We’ve seen species return through both wind-dispersed seeds and animal-assisted migration—proof of nature’s resilience.” Beyond ecological transformation, the eruption revolutionized volcanic monitoring. Before 1980, early warning systems focused largely on seismic tremors. The Mount St.

Helens crisis underscored the need for multidisciplinary vigilance—integrating GPS ground deformation, gas emissions tracking, and satellite thermal imaging. Today, similar systems in the Cascades—including the Cascades Volcano Observatory—benefit directly from lessons learned here. As USGS geologist Dr.

Jim Gawaris stated, “Mount St. Helens taught us that predicting eruptions isn’t just about earthquakes; it’s about understanding the full spectrum of precursory signals.” Climatically, the eruption injected roughly 10 billion tons of sulfur dioxide into the stratosphere, forming an aerosol veil that cooled global temperatures by up to 0.5°C in the northern hemisphere during 1981–1982. Satellite data confirmed a measurable impact on climate patterns, reinforcing volcanism’s role in Earth’s atmospheric dynamics.

Yet locally, the ash enriched soils, boosting agricultural productivity in downstream valleys—a paradox of destruction and renewal. Decades later, Mount St. Helens is not just a relic of 1980.

It is an active volcano, exhibiting renewed unrest since 2004: lava domes breached the surface, gas plumes rose several hundred feet, and minor explosions signaled magma’s slow ascent. This ongoing activity keeps the scientific community riveted, offering real-time insights into eruptive mechanics. For visitors and scientists alike, the mountain stands as both a memorial and a classroom.

Hiking trails carve through layers of geological history—exposed dacite rock, ancient forest stumps petrified in ash, and new growth pushing through barren ground. The mountain teaches immeasurably: that even catastrophe seeds renewal, that nature recovers with surprising tenacity, and that vigilance in the face of geological power remains essential. Mount St.

Helens endures not as a symbol of destruction—but as a dynamic force and a living testament to the Earth’s enduring capacity to heal, adapt, and evolve.

Related Post

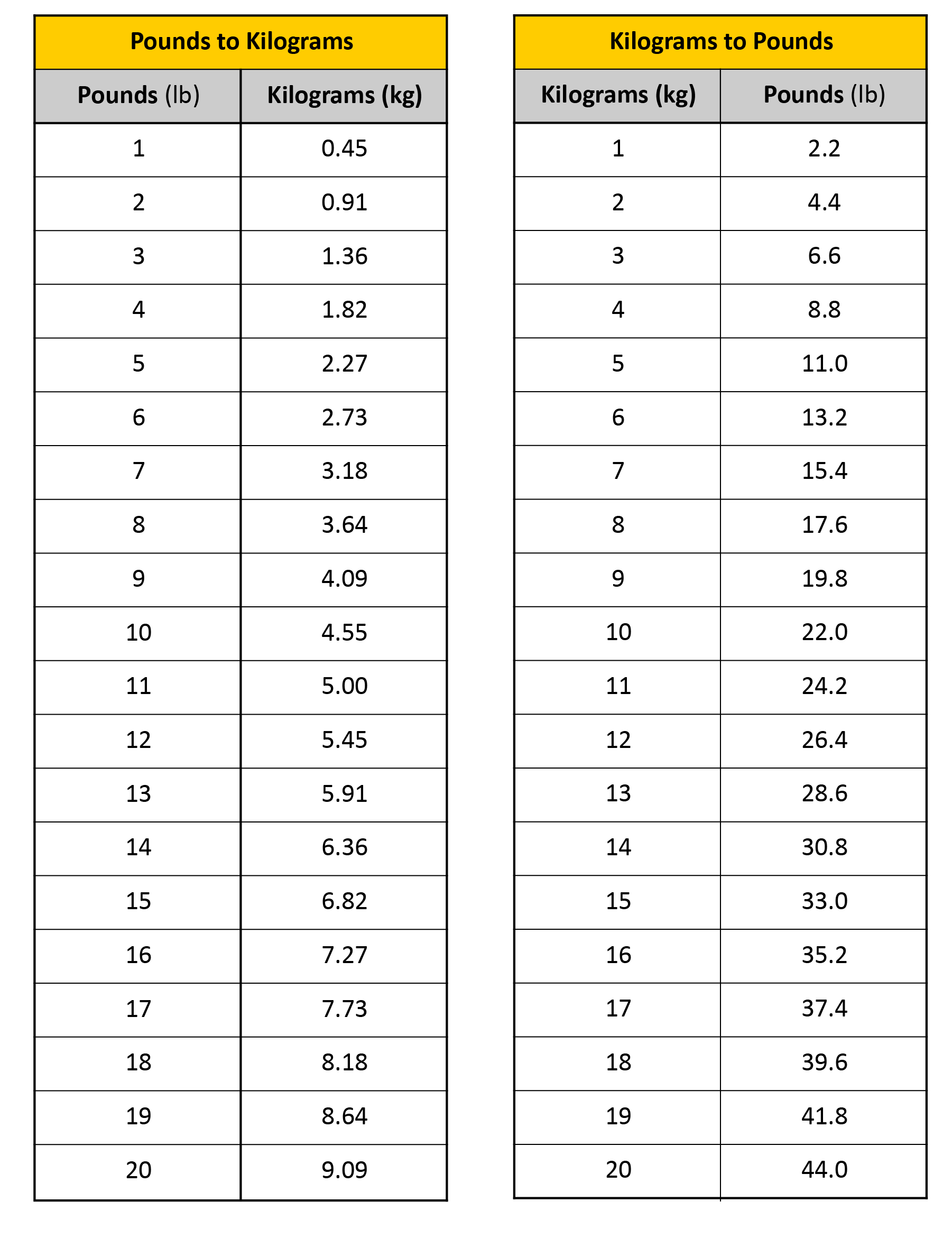

How 11,000 Grams Translate: The Definitive Guide to Converting Kilograms to Pounds for Global Accuracy

Gypsy Rose Blanchard and Dee Dee: Fragments of a Twisted Royalty

Naperville DMV Hours: Your Essential Guide to Illinois Vehicle Services

The Enduring Symbol of Resistance and Unity: The Philadelphia Phillies Emblem