Nitrogen’s Molecular Weight: The Key to Understanding Earth’s InvisibleWorkhorse

Nitrogen’s Molecular Weight: The Key to Understanding Earth’s InvisibleWorkhorse

Nitrogen, the most abundant gas in Earth’s atmosphere, plays a silent but indispensable role in sustaining life and driving industrial processes. With a molar mass of exactly 14.0067 grams per mole, this element’s simple atomic structure belies its complex influence across biological, environmental, and technological domains. Regardless of its atmospheric prevalence—constituting roughly 78% of air—nitrogen remains a cornerstone of modern science and engineering, especially when its precise molar mass is leveraged to decode molecular behavior.

Precision in Chemistry: Why Molar Mass Matters

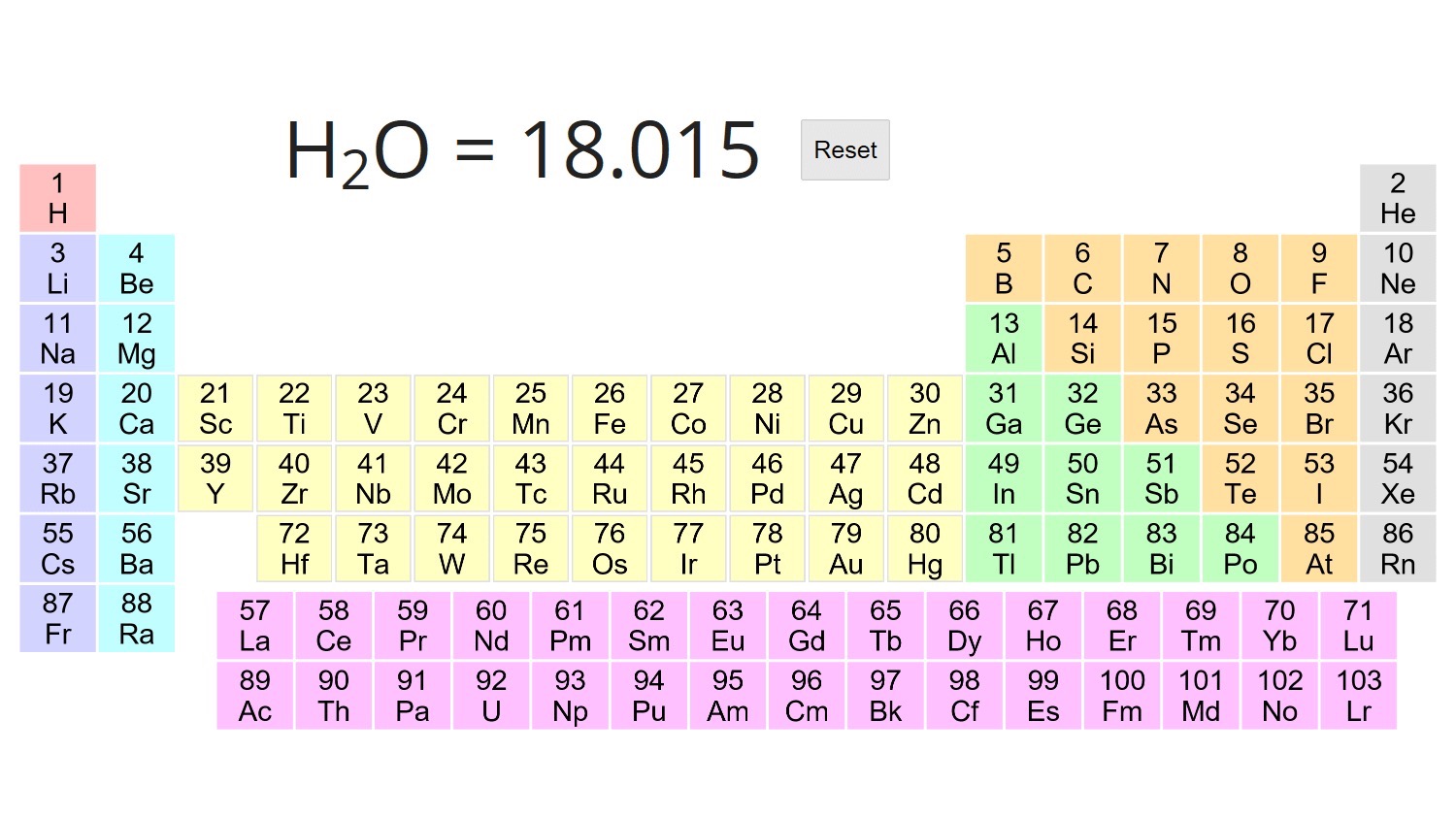

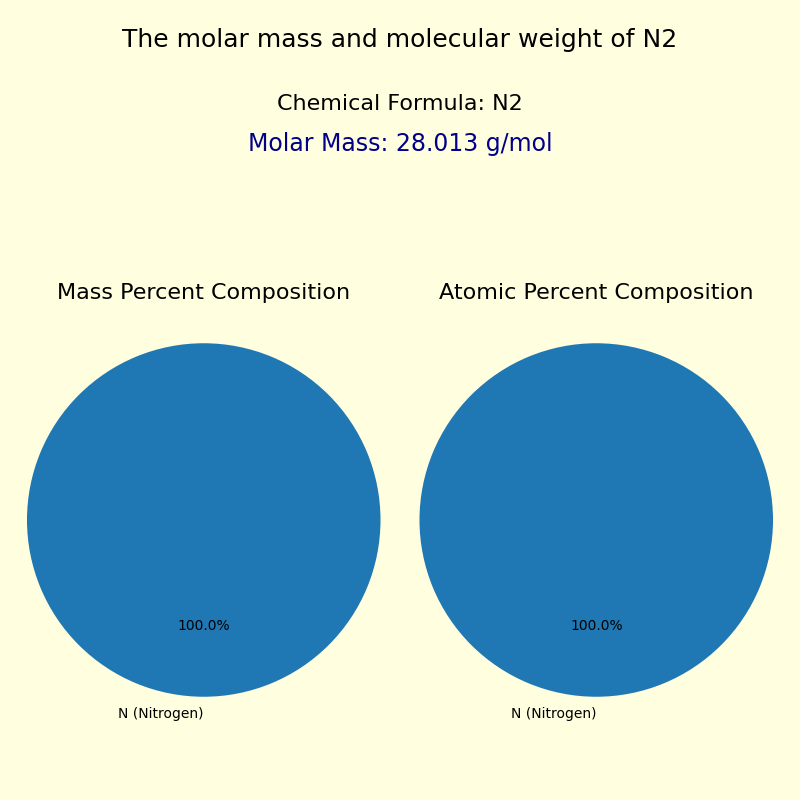

The molar mass of nitrogen—approximately 14.0067 g/mol—is a fundamental reference point in chemistry, enabling scientists to calculate stoichiometric relationships, trace reaction pathways, and predict physical properties. As the lightest of all stable elements, nitrogen’s low atomic weight arises from its single proton and typically seven neutrons (though isotopes vary slightly), resulting in a molecular formula of N₂, two nitrogen atoms covalently bonded. This diatomic structure defines its chemical inertness under normal conditions but also underpins its reactivity in artificial processes such as the Haber-Bosch synthesis, which produces ammonia for fertilizers.“Accurate knowledge of nitrogen’s molar mass is non-negotiable in chemical calculations—errors here ripple through yield predictions, safety assessments, and industrial efficiency,” notes Dr. Elena Torres, a physical chemist at the National Institute of Standards and Technology. Her work highlights how this precision supports everything from pharmaceutical formulations to nitrogen-based rocket propellants.

Breaking down nitrogen’s molar mass, each nitrogen atom contributes about 14 atomic mass units (amu), with 14.0067 g/mol reflecting natural isotopic abundance—primarily N-14 (~99.6%) and trace N-15. This subtle isotopic distribution, while minor, influences precision spectroscopy and mass spectrometry, where isotopic signatures reveal reaction origins and environmental cycling.

In atmospheric science, the molar mass helps quantify nitrogen’s role in heat transfer and air density. At sea level, dry air contains about 78% nitrogen molecules, with each N₂ molecule weighing roughly 28 atomic mass units.

When combined with oxygen (O₂ at ~32 amu) and trace gases, nitrogen’s molecular mass helps model atmospheric pressure gradients, weather patterns, and even orbital dynamics in spacecraft design.

Applications Beyond the Lab: From Fertilizers to Spacecraft

In agriculture, understanding nitrogen’s molar mass is critical to optimizing nitrogen fertilizers. The Haber-Bosch process—developed in the early 20th century—relies on precise molar ratios to convert atmospheric nitrogen into ammonia (NH₃), a transformation responsible for feeding billions but also raising concerns over runoff and emissions. “Every nitrogen atom we lock and release matters,” says environmental chemist Dr.Rajiv Mehta. “Efficient stoichiometry reduces waste and limits environmental impact.”

In medical contexts, nitrogen’s molar mass governs its use in cryotherapy and breathing mixtures. Liquid nitrogen, at ~28.0134 g/L (equivalent to N₂ molecules in vapor form), cools tissues during dermatological treatments and preserves biological samples.

In diving and aviation, nitrogen’s inertness and specific density—tied directly to its molecular weight—help engineers design pressurized habitats, where oxygen-nitrogen mixtures avoid hypoxia and decompression sickness.

Space exploration further underscores nitrogen’s utility. In spacecraft life support, nitrogen’s low reactivity and inert properties make it ideal for inerting fuel tanks and maintaining stable cabin atmospheres. Meanwhile, isotopic analysis of nitrogen in planetary atmospheres—from Mars to Titan—provides clues about past or present biological activity, leveraging subtle mass differences detectable through gas chromatography and mass spectrometry.

Isotopes and Accuracy: Tightening the Margins

While the standard molar mass of dry air’s nitrogen is cited as ~14.0067 g/mol, real-world samples exhibit slight variation based on geographic location and atmospheric conditions.Isotopic analysis confirms that most nitrogen is N-14, but up to 0.4% N-15 occurs naturally—or increases with human activity like fossil fuel combustion. “Modern analytical techniques now measure these isotopic shifts with laser precision, refining our understanding of nitrogen cycling,” explains Dr. Torres.

This isotopic sensitivity is vital in geochemistry. For example, ancient sedimentary records reveal shifts in N-15/N-14 ratios that signal past climate events, nutrient runoff, or even microbial evolution. In forensic science, tracing nitrogen isotopes in soil or tissue helps reconstruct environmental exposure, demonstrating the element’s role far beyond atmospheric dominance.

Environmental Implications: Nitrogen’s Double-Edged Sword

Though nitrogen supports life, its molar mass and chemical behavior underpin both sustainable cycles and pressing environmental challenges.Excess reactive nitrogen from fertilizers causes eutrophication, algal blooms, and dead zones in waterways—a consequence of human overuse magnified by nitrogen’s natural mobility and low energy cost to mobilize industrially.

Climate science also grapples with nitrogen’s role. While nitrogen (N₂) itself is a greenhouse gas with negligible warming potential, its compounds like N₂O—produced during microbial nitrogen cycling—are potent heat traps.

“Understanding nitrogen’s full molecular lifecycle, from atmosphere to soil,” argues Dr. Mehta, “is essential for developing sustainable nitrogen management strategies.”

The Future of Nitrogen Science

Advancements in quantum chemistry and machine learning now refine triglycerate-level modeling of nitrogen interactions, from enzyme catalysis in nitrogen fixation to nanoscale adsorption in catalytic converters. These tools depend critically on accurate molar mass inputs to simulate molecular behavior under extreme conditions—high pressures, low temperatures, or in non-equilibrium systems.Education and industrial standards continue to emphasize precision: chemical suppliers deliver nitrogen with certified purity and verified molar mass, while curricula stress the element’s centrality in interdisciplinary fields like biogeochemistry, materials science, and planetary exploration. “Nitrogen’s story is not just about its weight—it’s about how a single atom shapes planetary systems, human innovation, and ecological balance,” reflects Dr. Torres.

In essence, nitrogen’s molar mass—14.0067 g/mol—serves as a gateway to grasping its vast, layered significance. From the gravitation of ammonification in soil to the inertness that cools biological tissues, this fundamental value anchors a multitude of scientific and industrial frontiers. As global challenges demand tighter control over resources and emissions, mastery of nitrogen’s molecular identity remains not just academic, but essential to a sustainable future.

In the quiet strength of nitrogen’s molecular weight lies a profound influence—quiet, persistent, and indispensable across Earth’s systems and human endeavors.

Related Post

Sylvester Stallone Net Worth A Comprehensive Look At The Iconic Actors Wealth And Legacy Deep Dive Into His Welth Nd Success

Acceloration City: The Catalyst of the Next Urban Revolution

How Old Is Noah Wyle? Unraveling the Age and Legacy of a Hallmark Icon

Mary Davis Travis’ Birthday: A Quiet Catalyst for Reflection, Legacy, and Influence