Osmosis Unlocked: How This Passive Movement Powers Life at the Cellular Level

Osmosis Unlocked: How This Passive Movement Powers Life at the Cellular Level

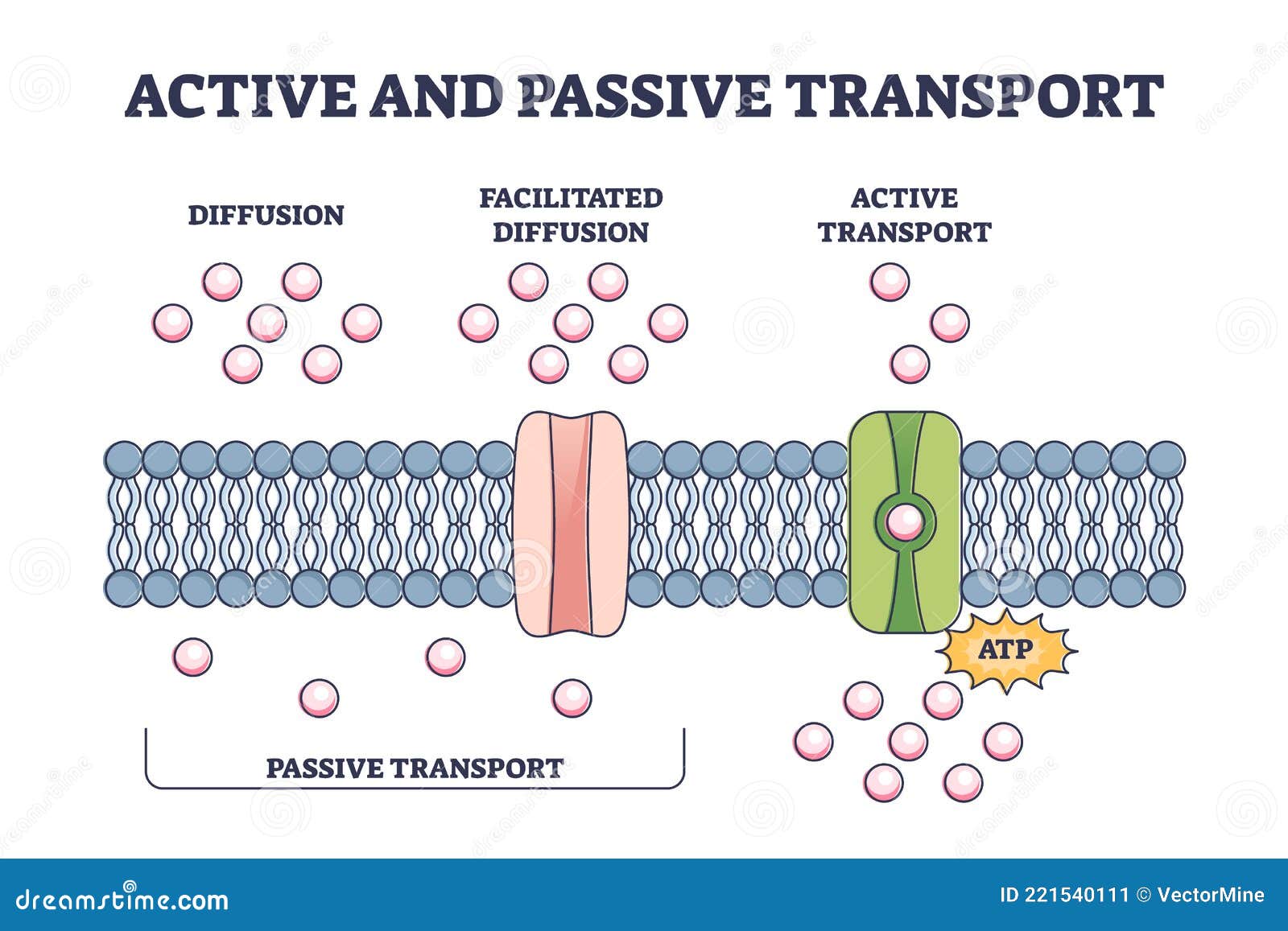

Osmosis stands as one of biology’s most fundamental and elegant mechanisms—an unseen yet vital force enabling cells to regulate water and maintain internal balance without expending energy. Unlike active transport, which requires ATP to drive molecular movement against concentration gradients, osmosis operates passively, driven solely by differences in water concentration across a semipermeable membrane. This physiological process powers everything from kidney function to nutrient absorption, revealing how life sustains itself through simple yet sophisticated molecular dance.

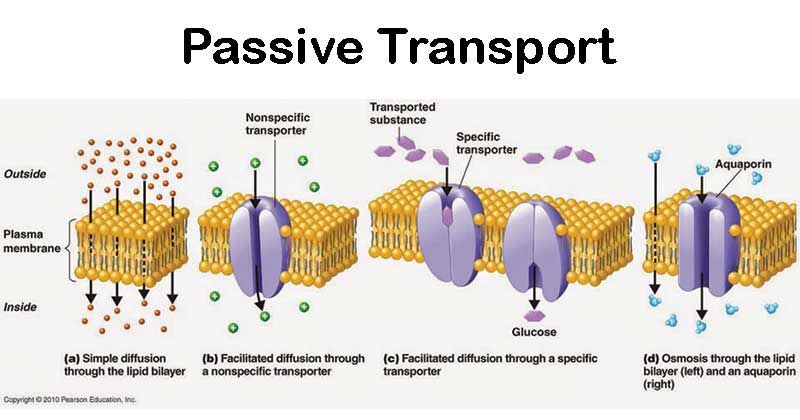

Understanding whether osmosis is active or passive is not just a matter of classification—it’s a key to unlocking the mechanics of cellular homeostasis and the design of biological systems. At the heart of osmosis lies a deceptively simple principle: water molecules migrate from regions of high concentration to low concentration, seeking equilibrium. This movement occurs through nonlocal, rate-limiting channels like aquaporins embedded in cell membranes—proteins that permit rapid flow without energy input.

As “water seeks its own level,” osmosis ensures cells neither swell unpredictably nor shrivel in dehydration. Each cell, from nerve neurons to red blood cells, depends on this passive flow to preserve volume, transmit signals, and support metabolic function.

Osmosis defies active transport in its reliance on a concentration gradient rather than metabolic energy.

While ATP-powered pumps like the sodium-potassium ATPase move ions against their gradients to establish conditions favorable for osmosis, osmosis itself requires no energy input. This distinction is critical: active transport builds internal disparities, whereas osmosis balances them, functioning as a natural, self-regulating process. The membrane—the gatekeeper of cellular life—permits only water molecules (and sometimes small uncharged solutes) to cross, maintaining selective permeability essential for passive water movement.

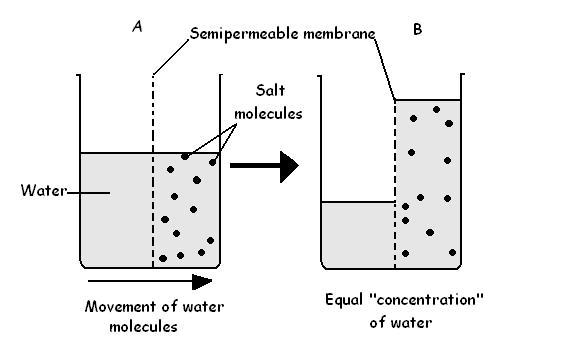

To understand osmosis, it helps to examine its core mechanics: diffusion followed by selective refinement. Diffusion describes the random motion of water molecules across a membrane. However, not all membranes are identical—semipermeable barriers—so osmosis specifically refers to the diffusion of water alone, driven by solute concentration differences.

Without energy, this passive flow continues until equilibrium is reached: a state where water movement across the membrane ceases, but solute concentrations remain unequal. This balanced condition sustains turgor pressure in plant cells, governs fluid exchange in kidneys, and enables nutrient uptake across intestinal epithelia.

Three key factors define the direction and efficiency of osmosis:

- Concentration Gradient: The stronger the disparity between water concentrations inside and outside a cell, the greater the osmotic pressure—and thus water flow.

This gradient acts as the engine powering osmosis without ever requiring direct energy expenditure.

- Membrane Permeability: Cells equipped with aquaporins allow rapid water passage, dramatically accelerating osmosis. In contrast, lipid bilayers alone restrict water flow, requiring specialized channels to facilitate diffusion at physiologically meaningful rates.

- Solute Environment: Dissolved solutes—ions, sugars, proteins—dictate water movement. Hypertonic solutions draw water out of cells; hypotonic solutions cause swelling; isotonic solutions maintain balance.

This principle underpins everything from cellular hydration to medical treatments involving isotonic IV fluids.

In medicine, osmosis is not merely a biological curiosity—it’s a cornerstone of therapeutic innovation. Intravenous saline solutions, designed with precise solute concentrations, exploit osmotic gradients to restore fluid balance in dehydrated patients.

In patients suffering from hyponatremia, where low blood sodium levels cause dangerous cellular swelling, carefully controlled hypertonic saline induces osmotic water movement out of brain cells, reducing intracranial pressure. Similarly, osmotic diuresis in kidney care harnesses mannitol—a potent osmotic agent—to draw excess fluid from tissues, aiding in conditions like cerebral edema or acute kidney injury.

Plant biology

Related Post

Is The Guardian A Good Newspaper? A Deep Dive into Quality Journalism in the Digital Age

Is Midday Green Loan That Green Loans Legit? Reddit Reviews and Real Insights on a Rising Financing Trend

Defining ‘Exclude’ with Precision: What It Means and Why It Matters Across Domains

Strategic Intervention Material: The Science Behind Transforming Behavioral Outcomes with Precision