Presidents and Their Parties: How Ideology Shaped America’s Highest Office

Presidents and Their Parties: How Ideology Shaped America’s Highest Office

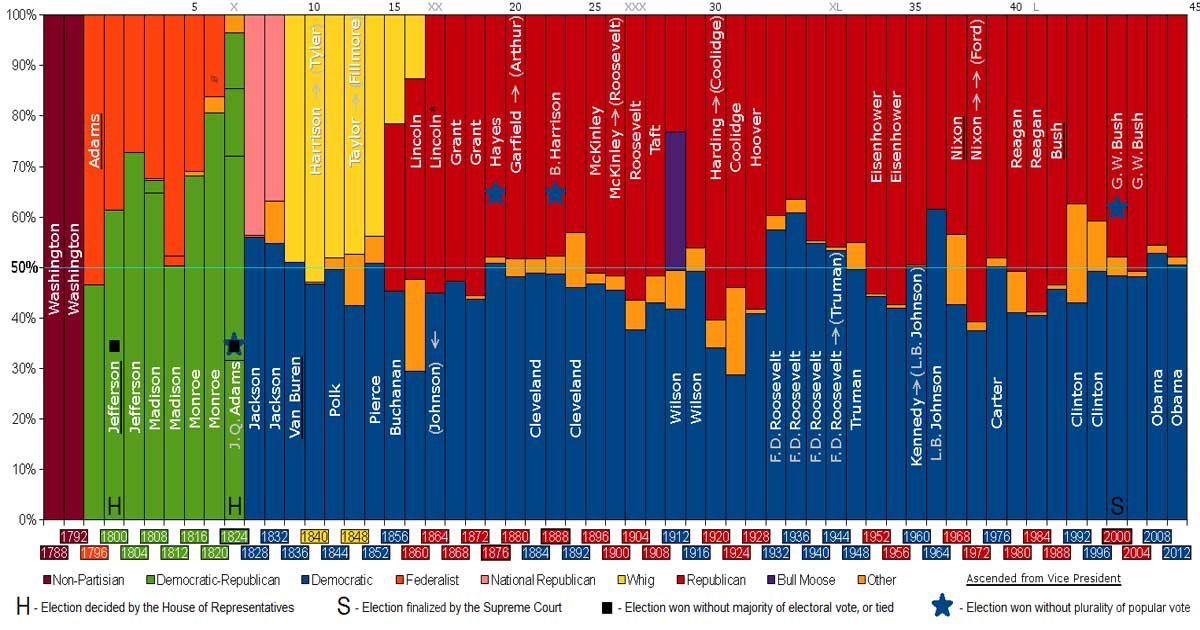

From the founding era’s early partisan divides to today’s polarized landscape, the political affiliations of U.S. presidents reveal not just individual beliefs, but the evolving arc of American governance. The relationship between presidential leadership and political party remains one of the most telling indicators of national direction, reflecting shifting coalitions, ideological battles, and the enduring tension between tradition and change.

This exploration traces key presidents and their party allegiances, highlighting how these alignments shaped policy, stoked division or unity, and defined America’s democratic experiment across generations.

The Birth of American Partisanship: Washington, Adams, and the Foundational Rift

The earliest struggle over party alignment began during George Washington’s presidency, when his cabinet fractured over economic and foreign policy, giving rise to the nation’s first political factions. Though Washington cautioned against permanent party systems, his administration witnessed the emergence of two opposing visions: Federalists, led by Alexander Hamilton, championed a strong central government and pro-business economics, while Democratic-Republicans, guided by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, emphasized states’ rights and agrarian ideals.> “The party spirit is already in full strain,” Washington warned in his Farewell Address, foreseeing how ideological splits could become more enduring than policy disputes alone. Though he advised unity, the divergence settled into rival groups whose influence persists. John Adams, a Federalist, continued this legacy, signing the Alien and Sedition Acts—policies reflecting Federalist fears of mob rule—further entrenching party lines as tools of governance.

By the 1790s, party identity was no longer just organizational—it became a battleground over the very soul of the republic. The Federalists, rooted in urban elites and financial modernization, clashed with the Democratic-Republicans, representing rural interests and a limited federal role. This conflict laid the groundwork for America’s two-party system, where ideology and opportunity would continue to converge and collide.

The Civil War and Reconstruction: Lincoln and the Republican Dominance

Abraham Lincoln’s election in 1860 marked a seismic shift, as the Republican Party—forged explicitly in opposition to slavery’s expansion—rose to national power.Lincoln’s leadership during the Civil War cemented Republican identity as the party of union and emancipation, though its base remained fragile in the early years. The post-war era saw Reconstruction policies deepen partisan divides, with Republicans pushing for civil rights and federal oversight in the South, while Democratic opposition simmered, eventually fueling the “Solid South” during the late 1800s. > “A house divided against itself cannot stand,” Lincoln famously declared, framing the nation’s crisis as a choice between governance flawed by sectionalism or unity forged through justice.

His presidency embedded the Republican Party not only as a political force but as an ideological standard-bearer of national reconciliation and reform.

Though Reconstruction’s end weakened federal enforcement, the Republican Party’s early alignment with abolitionist and industrial progressives set a precedent: American politics would be defined by competing visions of liberty, governance, and economic order—visions shaped by deep party loyalties and national imperatives.

The Progressive Era and New Deal: Shifting Loyalties and Ideological Realignment

The late 19th and early 20th centuries brought transformation as populist and progressive movements reinvigorated Democratic numbers, shifting party coalitions. Presidents like Woodrow Wilson and Franklin D.Roosevelt redefined party platforms, reallocating power toward labor, rural voters, and reformers. FDR’s New Deal coalition—united behind bold federal intervention—rewrote the Democratic Party’s identity, making it the party of active government and social safety nets. > “The test of our progress is not whether we add more numbers; it is whether we do justice to the people,” FDR declared, encapsulating a new era where party loyalty was measured less by geography than by economic and social philosophy.

This transformation realigned American politics: Southern Democrats, once allies of the Republican Confederacy, drifted toward the GOP as racial policies and urban reforms deepened division. By mid-century, Republican appeal among conservative, pro-business, and religious conservatives grew, especially under Dwight D.

Related Post

From Ford to Biden: A Partisan Journey Through Every U.S. President

Uva Tea: Benefits, Side Effects, And Uses

How Many Eyelashes Do We Truly Have? Decoding the Fascinating Truth Behind Our Upper & Lower Lash Count

Softball World Series Schedule: The Crucial Calendar Driving Global Elite Competition