Reactant of Glycolysis: The Crucial First Step in Cellular Energy Production

Reactant of Glycolysis: The Crucial First Step in Cellular Energy Production

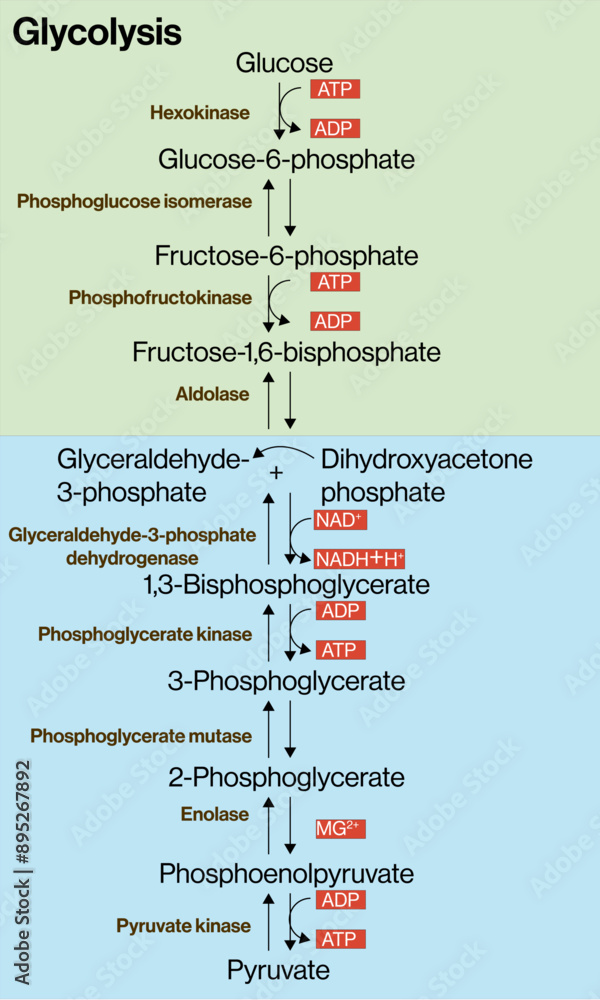

Glycolysis, the foundational metabolic pathway driving energy production in nearly all living cells, begins with a single pivotal molecule: glucose. This six-carbon sugar serves as the reactant that initiates a cascade of enzymatic reactions, transforming biochemical energy into usable forms while fueling vital cellular functions. As the gateway to energy metabolism, understanding the reactant of glycolysis reveals not only the mechanics of this ancient process but also its central role in health, disease, and evolutionary biology.

The reactant most universally studied in glycolysis is glucose—specifically, its 6-carbon hexose structure in the form of D-glucose, which cells rapidly phosphorylate to trigger downstream metabolic activity. Glucose enters glycolysis in the cytoplasm, where it becomes the primary substrate upon which a series of ten enzyme-mediated reactions operate with remarkable precision. As biochemist Arthur Kornberg once noted, “Glucose acts as the molecular latch that unlocks energy extraction, making it indispensable to aerobic and anaerobic metabolism alike.” This initial phosphorylation step—converting glucose to glucose-6-phosphate—requires ATP but sets the stage for efficient energy processing.

Biochemical Structure and Function of Glucose in Glycolysis

Glucose, a monosaccharide with the molecular formula C₆H₁₂O₆, exists predominantly as a ring structure in physiological conditions—typically a six-membered pyranose form under cellular conditions. This structural conformation is critical: it enables selective interactions with key enzymes such as hexokinase and glucokinase, which catalyze the rate-limiting first phosphorylation. The hydroxyl groups on each carbon position create multiple reactive sites, allowing precise enzymatic targeting essential for pathway accuracy.The transformation begins when hexokinase binds glucose and ATP, catalyzing the transfer of a phosphate group to produce glucose-6-phosphate. This reaction (“glucose plus ATP → glucose-6-phosphate plus ADP”) not only traps glucose inside the cell—preventing its escape—but also primes it for subsequent steps by making the 6-phosphate intermediate energetically unfavorable to revert to glucose. As Nobel Prize-winning metabolism researcher Otto Warburg emphasized, “The first commitment in glycolysis—phosphorylation of glucose—is irreversible and defines the pathway’s existence.”

Key intermediates include fructose-6-phosphate and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate, both formed through intermediate rearrangements.

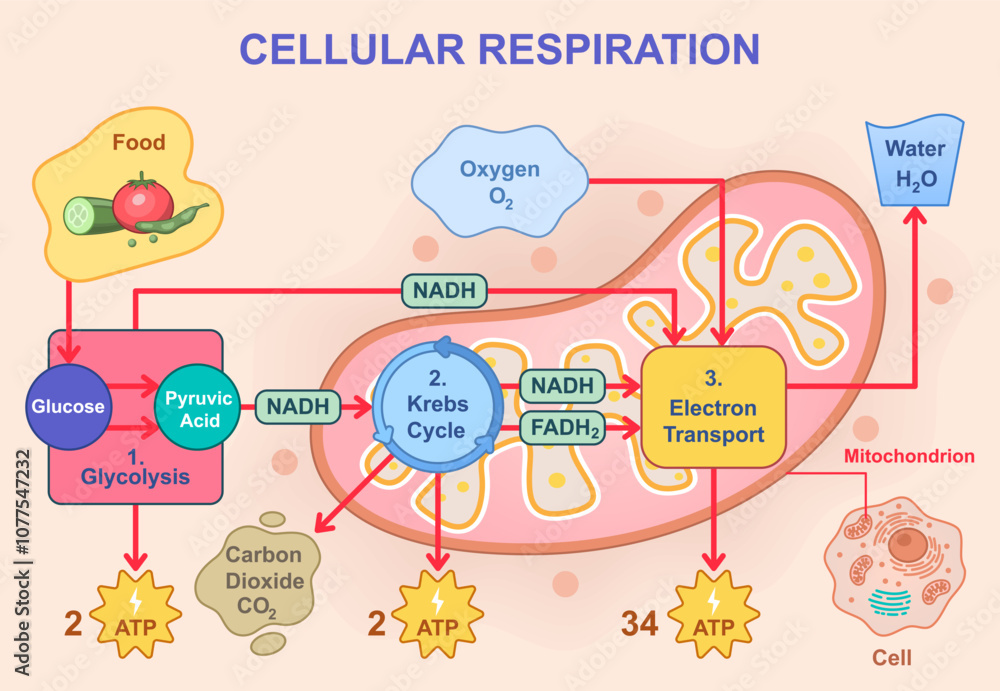

Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate, in particular, becomes central in the energy-capturing steps: it is oxidized and phosphorylated twice per glycolysis cycle, yielding ATP through substrate-level phosphorylation. By the end of glycolysis, a single glucose molecule is split into two molecules of pyruvate, yielding a net gain of two ATP molecules and two NADH—key outputs that feed into later metabolic processes like the citric acid cycle and oxidative phosphorylation.

Enzymatic Mechanisms Acting on Glycolytic Reactants

The progression through glycolysis depends on a tightly regulated suite of enzymes, each specific to a reactant or intermediate.Hexokinase operates broadly across tissues but varies in isoform expression—liver-centric glucokinase exhibits different kinetic properties ideal for glucose homeostasis. Phosphofructokinase-1 (PFK-1), considered the committed enzyme of glycolysis, catalyzes the conversion of fructose-6-phosphate to fructose-1,6-bisphosphate, a rate-limiting step governed allosterically by ATP, citrate, and AMP levels. At the heart of glycolysis lies phosphoglycerate kinase, which transfers a phosphate from 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate to ADP, generating ATP and 3-phosphoglycerate.

The enzyme glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase then oxidizes this intermediate, reducing NAD⁺ to NADH while phosphorylating ADP to ATP—a vital energy-capturing step. Industrial and clinical research relies heavily on monitoring these enzymatic fluxes, as dysregulation contributes to metabolic diseases such as glycolytic defects, cancer metabolism (Warburg effect), and diabetes.

Regulatory feedback loops ensure glycolysis responds dynamically to cellular energy status.

For example, high levels of ATP inhibit PFK-1, slowing glycolysis when energy demand is met. Conversely, low ATP or high AMP activate key enzymes, accelerating glucose breakdown. This fine-tuning prevents wasteful ATP production and supports metabolic flexibility across varying physiological states.

Physiological Significance Across Organisms and Cells

Glycolysis, operating in nearly every cell type from human neurons to yeast, exemplifies metabolic universality. In human erythrocytes—cells lacking mitochondria—glycolysis is the sole energy source, highlighting its indispensable role. Even in rapidly dividing cancer cells, enhanced glycolytic activity supports biosynthesis and survival in low-oxygen environments, a phenomenon central to tumor metabolism research.The reactant glucose not only energizes cells but also fuels biosynthetic pathways: intermediates feed into amino acid synthesis, lipid production, and nucleotide formation. As biochemist Leonor Michaelis observed, “Glucose is metabolically versatile—it bridges catabolism and anabolism, bridging energy with structure.” This duality positions glycolysis as a metabolic nexus where energy extraction converges with cellular growth.

Clinical and Research Frontiers

Dysfunction in glycolytic reactants or enzymes manifests in severe pathologies.Glucokinase defects cause maturity-onset diabetes of the young type 2, impairing glucose sensing and insulin secretion. Mutations in PFK-1 lead to glycogen storage disease type V, where muscle fatigue and cramping result from impaired ATP production. These examples underscore glycolysis’s medical relevance and the precision required in targeting its components for therapy.

Emerging research explores glycolysis modulation in oncology, aiming to exploit the Warburg effect by inhibiting glucose uptake or known glycolytic enzymes. NH₂G-filled glucose analogs and PFK-1 inhibitors are under investigation to selectively target cancer metabolism. Meanwhile, metabolic engineering seeks to enhance glycolytic efficiency in industrial bioproduction, from biofuels to pharmaceuticals.

From molecular mechanics to whole-organism physiology, the reactant of glycolysis—glucose—functions as both a gateway and a hub. Its transformation initiates a high-efficiency energy

Related Post

The Astonishing Career of Prince: Iconic American Singer, His Life, Legacy, and 12 Most Unforgettable Gigs & Tours

Unleashing Premium Cinema at Your Fingertips: How 6Movies Stream Rewrites the Streaming Experience

Pseijimse Gardner: Unlocking the Legacy of a Modern Thought Leader

How Usa Com Email Is Redefining Secure, Efficient Communication