The Columbian Exchange: How a Global Revolution Redefined Food, Faith, and Fate

The Columbian Exchange: How a Global Revolution Redefined Food, Faith, and Fate

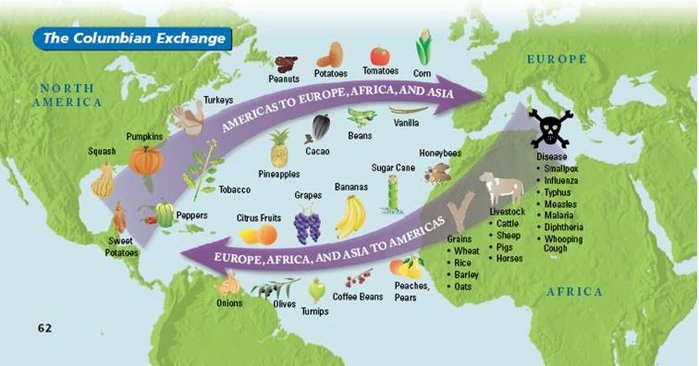

From 1492 onward, a seismic transformation reshaped human civilization across continents — not by conquest or technology alone, but through the silent flow of seeds, animals, diseases, and ideas across the Atlantic. This historic interchange, known formally as the Columbian Exchange, describes the massive transfer of plants, animals, people, technology, and pathogens between the Old World and the New World after Christopher Columbus’s first voyage. More than a simple exchange, it was a catalyst for ecological upheaval, demographic collapse, and culinary metamorphosis.

Beneath the specter of devastation—epidemics that ravaged Indigenous populations and the forced displacement of millions—lies a profound and enduring transformation in global agriculture and diet. As historian Alfred Crosby famously observed, “the Old World gave the New, and the New gave the Old far more than they imagined.” This partnership of destruction and renewal forged the foundations of modern food systems, changing what and how people ate from Ireland to Mexico and beyond.

The Biological Blueprint: What Were the Core Exchanges?

At its essence, the Columbian Exchange was two-sided: crops and livestock moved west, while diseases and, in the centuries that followed, new farming practices flowed east.From Europe, Africa, and Asia, sugarcane, wheat, rice, and domesticated livestock—cattle, pigs, sheep, goats—found new homes in the Americas. These animals revolutionized land use and diet, enabling large-scale animal husbandry and altering landscapes once dominated by wild woodlands. Wheat, for example, took root in the fertile soils of North America, becoming a staple for settlers and redroot grid farmers alike.

Conversely, New World crops rapidly reshaped Old World gastronomy and agriculture. Terminology such as “Columbian Exchange Synonym” captures this reciprocal flow—crops like maize (corn), potatoes, tomatoes, cacao, and chili peppers spread globe-sparingly but irreversibly. “Tomatoes alone transformed Mediterranean cuisine,” notes food historian Michael Krondl, “going from symbolizing danger to being the soul of Italian cooking.” Similarly, the potato—drought-resistant and calorific—became a dietary linchpin across Europe, helping sustain population booms in Ireland, Russia, and Eastern Europe.

Tomatoes, originally dismissed as ornamental or even poisonous in Europe, became indispensable in Spanish, Italian, and later American dishes. Potatoes, thriving in cooler climates, supported urban growth and industrial labor forces. Maize spread through sub-Saharan Africa and southern Asia, reshaping subsistence farming and supplementing staple diets.

Cacao, revered by Mesoamerican cultures, was reborn in Europe as the luxury bean integral to chocolate’s global journey.

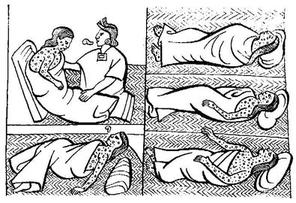

Human Impact: Epidemics, Slavery, and Demographic Swapbooks

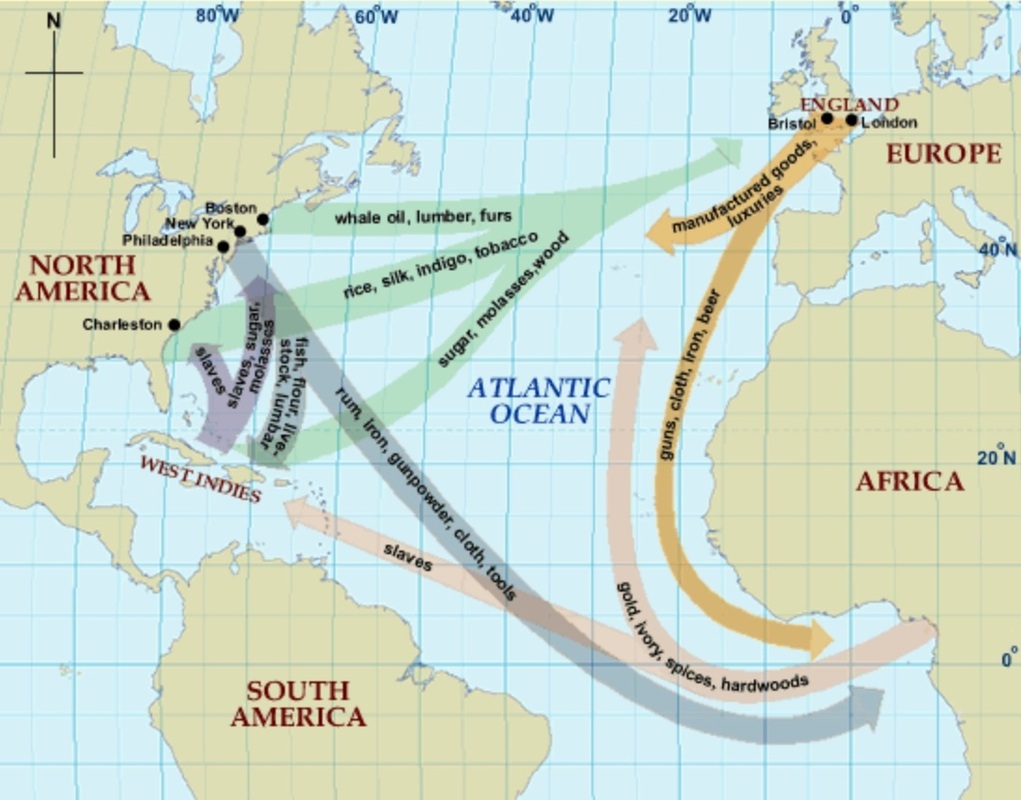

The human toll of the Columbian Exchange was as staggering as its biological reach. As colonists and enslaved Africans moved across oceans, where immunities had not evolved, pathogens surged as invisible weapons.Smallpox, measles, influenza, and typhus—carried by Europeans—devastated Indigenous populations with casualty rates exceeding 90% in some communities. Neurologist Charles Rosenberg describes the tragic paradox: “Diseases the Old World wore away step by step were instantly lethal in societies whose immune systems had never encountered them.” This demographic collapse triggered a chain reaction across continents. To replace dwindling Indigenous labor, European powers accelerated the transatlantic slave trade, forcibly importing millions of Africans to the Americas.

The triangular trade system—sugar, molasses, rum—became both economically lucrative and morally catastrophic. African societies were destabilized, while the Americas began a rapid shift from Indigenous-dominated populations to a racially mixed workforce. In agricultural shifts, the displacement of native peoples led to land abandonment and rewilding in some regions, altering ecosystems and carbon cycles.

Meanwhile, the importation of African and European livestock transformed land use, with cattle ranching spreading across the Americas—from Argentina to Texas—sown into the cultural fabric of ranching communities and beef consumption.

Culinary Tipping Points: From New World Ingredients to Global Palettes

Beyond survival, the Columbian Exchange forever altered global cuisine. What began as marginal proved essential: chili peppers ignited the fiery profiles of Indian curries, Mexican mole, and Sichuan spice; vanilla and cacao evolved from Mesoamerican sacred imports into luxury commodities that defined European confectionery.Corn, once a niche crop along the Mississippi, now fuels ethanol, bird feed, and gluten-free foods worldwide. Tomatoes, initially regarded with suspicion, became the soul of Mediterranean gastronomy— Sicily’s sun-ripened sauces, Spain’s gazpacho, and the foundation of Italian pasta sauces. The “potato era,” as historian David Blackmur terms it, supported urbanization and industrial labor in Europe, enabling demographic surges and shifting class dynamics.

Francis evolutionary biologist Jared Diamond asserted, “Without Old World crops, the Americas might not have fed their growing populations; without New World crops, Europe’s rise would have been far more constrained.” Even spices, though pre-existing in Eurasia, saw intensified use and mixing through Columbian-era globalization. Cinnamon, cloves, and nutmeg—already traded via complex networks—gained new prominence in diets fueled by carbohydrate-rich New World staples. The Columbian Exchange Synonym encapsulates not just a historical episode but an enduring transformation—one where biology and culture collided, reshaping diets, economies, and ecosystems across an entire planet.

From potato fields to spice markets, from settlers’ cabins to bustling colonial cities, the ripple effects endure. What began as an accidental transfer of lifeforms grew into a global revolution, embedding foreign seeds and pathogens into the very identity of civilizations. In every bite of tomato sauce, every bite of bread, every sip of chocolate, the legacy lives—silent, profound, and unmistakably global.

Related Post

How To Private Message on Roblox: Master Secure, Real-Time Communication in the Metaverse

Chihuahua, Mexico: Where a Tiny Dog Inspires a City’s Identity

From Watchseries8 to Blockbusters: The Seamless Evolution of Your Favorite Shows into Hollywood Films

Ikea.Com: The Global Blueprint of Affordable, Thoughtful Home Design