The Fall of Religious Refuge: Unraveling the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes

The Fall of Religious Refuge: Unraveling the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes

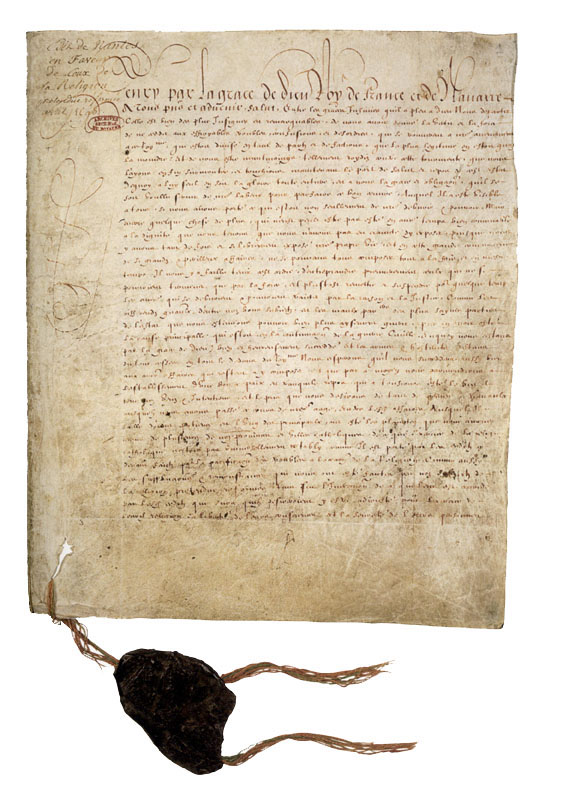

In 1685, France’s King Louis XIV issued a dramatic decree that shattered a century of fragile tolerance: the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes. This historic act nullified centuries of modest religious coexistence for French Protestants—Huguenots—by outlawing their worship and stripping them of legal protections. What began as an effort to consolidate royal authority and unify the realm under Catholicism triggered a profound crisis of liberty, migration, and state power, reshaping European religious dynamics and foreshadowing modern issues of persecution and exile.

The revocation marked not just the end of a policy but the collapse of a vision—one legal safeguard—intended to prevent sectarian violence in a fractious France. The Edict of Nantes, originally promulgated in 1598 by Louis XIII in the aftermath of devastating religious wars, had granted Huguenots substantial rights, including freedom of worship, control over fortified towns, and access to civil offices. French historian Jean-Marie Constant describes the edict as “a bold experiment in pluralism”: “It allowed coexistence where bloodshed once reigned.” For decades, this compromise held, enabling Protestant communities to thrive alongside Catholics.

Yet, under Louis XIV—determined to rule as the “Sun King” and embody absolute Catholic monarchy—religious homogeneity became a symbol of legitimacy.

Each year before 1685, Huguenots had enjoyed defined but limited freedoms that made their integration possible. However, by the 1670s, pressures mounted to eliminate Catholic dissent.

Louis XIV, advised by devout ministers like François de Hardouin, Comte de Torcy, viewed Protestantism as both a political threat and a challenge to royal sovereignty. “A single Church, one King, one realm—this was the prize,” declared royal propaganda of the era. The king saw the Edict not as a charter of rights but as a concession that could not be sustained.

The final blow came in October 1685 with the formal revocation, announced by royal decree and reinforced by a decree of forced conversions.

The immediate aftermath was devastating. Thousands of Huguenots faced persecution: Catholic authorities banned Protestant services, destroyed churches, and imprisoned pastors.

Discriminatory policies escalated: children were taken from Protestant homes, public offices were closed to non-Catholics, and outdoor worship was punishable by death. Estimates suggest between 200,000 and 400,000 Huguenots fled France—among them skilled artisans, merchants, scholars, and military officers. Led by routes through the Netherlands, Switzerland, England, and Prussia, this diaspora transformed regional economies and intellectual spheres.

As historian Natalie Zemon Davis observed, “These exiles carried seeds of change: Enlightenment ideas, industrial techniques, and religious dissent that would fuel transformation across Europe.”

The revocation’s impact extended far beyond individual suffering. France lost a significant portion of its productive middle class during a period of mercantilist expansion, weakening its economic competitiveness relative to Protestant powers like the Dutch Republic and England. Meanwhile, Protestant nations welcomed refugees, strengthening their borders and bolstering anti-A cannedal sentiment toward Louis XIV’s absolutism.

The policy intensified European tensions, reinforcing alliances that resisted French hegemony. Moreover, revocation underscored the peril of state-sponsored religious uniformity—foreshadowing later conflicts over civil rights and freedom of conscience.

From a legal standpoint, the revocation represented a sweeping reversal to France’s legal framework.

The Edict of Nantes had established a precedent for minority rights within a Catholic monarchy. Its annulment dismantled this framework entirely, replacing it with enforced orthodoxy. Church courts regained power, and royal edicts became the ultimate arbiter of belief.

Yet this centralization did not end dissent. Underground Protestant communities persisted, preserving faith in secret through clandestine schools, coded writings, and memorized liturgies. The resilience of Huguenots in maintaining identity under duress remains a powerful testament to human perseverance.

The Revocation of the Edict of Nantes thus stands as a pivotal moment in European history—a case study in how political ambition and religious intolerance can dismantle hard-won pluralism. It marked the end of a tentative tolerance era, accelerated the outflow of a vital demographic, deepened religious divides, and ultimately contributed to the long arc of Enlightenment arguments for religious liberty. As modern democracies continue to grapple with diversity and inclusion, the lessons of 1685 remain urgent: that the hard-won right to worship freely is fragile, and its protection defines the soul of civilization.

The revocation was more than a royal decree—it was a turning point that revealed the costs of absolutism and the enduring power of faith. It reshaped not only France but the broader European order, leaving a legacy etched in memoirs, migrations, and the ongoing struggle for religious freedom.

Related Post

Telat Cicilan’s Seminggu Mobil: A Cultural Turnover Shaping Communication, Community, and Consumption

Brampton & Toronto Time: What Timing Means for Commuters, Businesses, and Life in Two Majorsenters

Unlock Full Transparency: How the Consulta De Registro Federal de Contribuyentes Transforms Tax Accountability in Venezuela

Kingston vs Montego Bay: Jamaica’s Twin Cities Compete for Prime, But Montego Bay Takes the Crown as the Island’s Largest Urban Hub