The Turbulent Decade: Presidents and Power in the 1960s

The Turbulent Decade: Presidents and Power in the 1960s

The 1960s were a decade of profound transformation, marked by seismic social upheaval, Cold War brinkmanship, and presidential leadership that shaped both American identity and global destiny. Four presidents—Dwight D. Eisenhower’s lingering influence, John F.

Kennedy’s electrifying presence, Lyndon B. Johnson’s legislative ambition, and Richard Nixon’s ensuing pragmatism—navigated crises that tested the nation’s values and institutions. As civil rights movements surged, Vietnam escalated, and technological frontiers expanded, these leaders confronted challenges that redefined executive power, public trust, and the role of government.

Their actions, decisions, and legacies remain central to understanding 20th-century America.

John F. Kennedy, elected in 1960 at age 43, brought youth and idealism to the White House, promising a “New Frontier” of progress on civil rights, space exploration, and Cold War strategy.

Though his tenure lasted barely three years—cut short by assassination—his vision set the stage for the turbulent era ahead. Kennedy’s handling of the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962, when he led the nation through the most dangerous moment of the Cold War, demonstrated a blend of resolve and diplomacy. As he later declared, “We face danger—not because we fear our enemies, but because we dare not to meet them.” This measured approach contrasted sharply with the escalating conflict in Vietnam, where his administration deepened U.S.

military involvement, laying groundwork that his successor would inherit and expand.

Dwight D. Eisenhower, though no longer in office during the 1960s, cast a long shadow.

His two terms (1953–1961) established critical precedents: the modern military-industrial complex, the doctrine of containment against communism, and cautious modernization of civil rights through federal authority—most notably in his 1957 deployment of meters troops to enforce school integration in Little Rock, Arkansas. As historian//

The Escalation of Vietnam: From Eisenhower to Johnson

From Stability to Deployment: The Shifting Path The 1960s began under the cautious stewardship of President Eisenhower, whose administration viewed Vietnam as a fragile Cold War outpost against communist expansion. Eisenhower authorized quiet support for Ngo Dinh Diem’s regime in South Vietnam, fearing the domino effect of communist victories across Southeast Asia.Yet it was Johnson who transformed Vietnam from a diplomatic concern into a full-scale military commitment. By 1964, following the Gulf of Tonkin incident—where U.S. destroyers reported multiple torpedo attacks—Congress responded with the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, granting Johnson broad war powers.

By year’s end, over 184,000 troops occupied Vietnam. Johnson’s escalation reached a turning point with over half a million U.S. combat soldiers deployed by 1968, yet public trust eroded as the war dragged on without clear success.

“We’re not going to Vietnam because we fear a defeat abroad, but because we love a hope for peace,” Johnson declared in 1964, framing his intervention as one of global responsibility. But as casualties mounted and anti-war sentiment surged, the promise of victory proved elusive. The war became a defining crisis of the decade, exposing deep divisions and reshaping presidential accountability.

Civil rights advanced rapidly under Kennedy’s incremental but determined leadership, even as resistance in the South remained fierce. His administration used federal power—through lawsuits, executive orders, and selective deployments—to protect civil rights workers, most notably during the 1961 Freedom Rides and the University of Mississippi integration crisis. Kennedy’s June 1963 televised speech, asserting “the time for vigilant action is now,” marked a rare presidential impetus for legislative change.

Though the revenant Violence against activists drew admiration and outrage, his assassination in November 1963 left the movement’s momentum critical—and vulnerable. From Law to Legacy: The Civil Rights Act of 1964 Though Kennedy did not live to see it, his administration laid essential legal groundwork for the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964—a sweeping law banning segregation in public spaces and employment discrimination. The bill passed under Johnson’s leadership after Kennedy’s death, succeeding where political momentum had stalled.

Simultaneously, the administration’s growing conflict with South Carolina’s Jim Crow regulations signaled a new federal resolve. As historian Taylor Branch observed, “The 1960s began with hesitation, but ended with transformation—driven by presidents willing to act, even when the nation split.”

Richard Nixon’s entry into the 1960s further diversified presidential engagement with national and global challenges. Though he lost the 1960 election (and returned to private life), Nixon reemerged in 1968 on a platform of law-and-order and Vietnam disengagement, promising to end the war “with honor.” His pragmatic approach—mediated through secret negotiations and backchannel diplomacy—reflected a shift toward realpolitik in presidential strategy.

Nixon’s approach to diplomacy, including early overtures to China and détente with the Soviet Union, foreshadowed a new Cold War mindset that would expand executive influence beyond military force.

Beyond foreign

Related Post

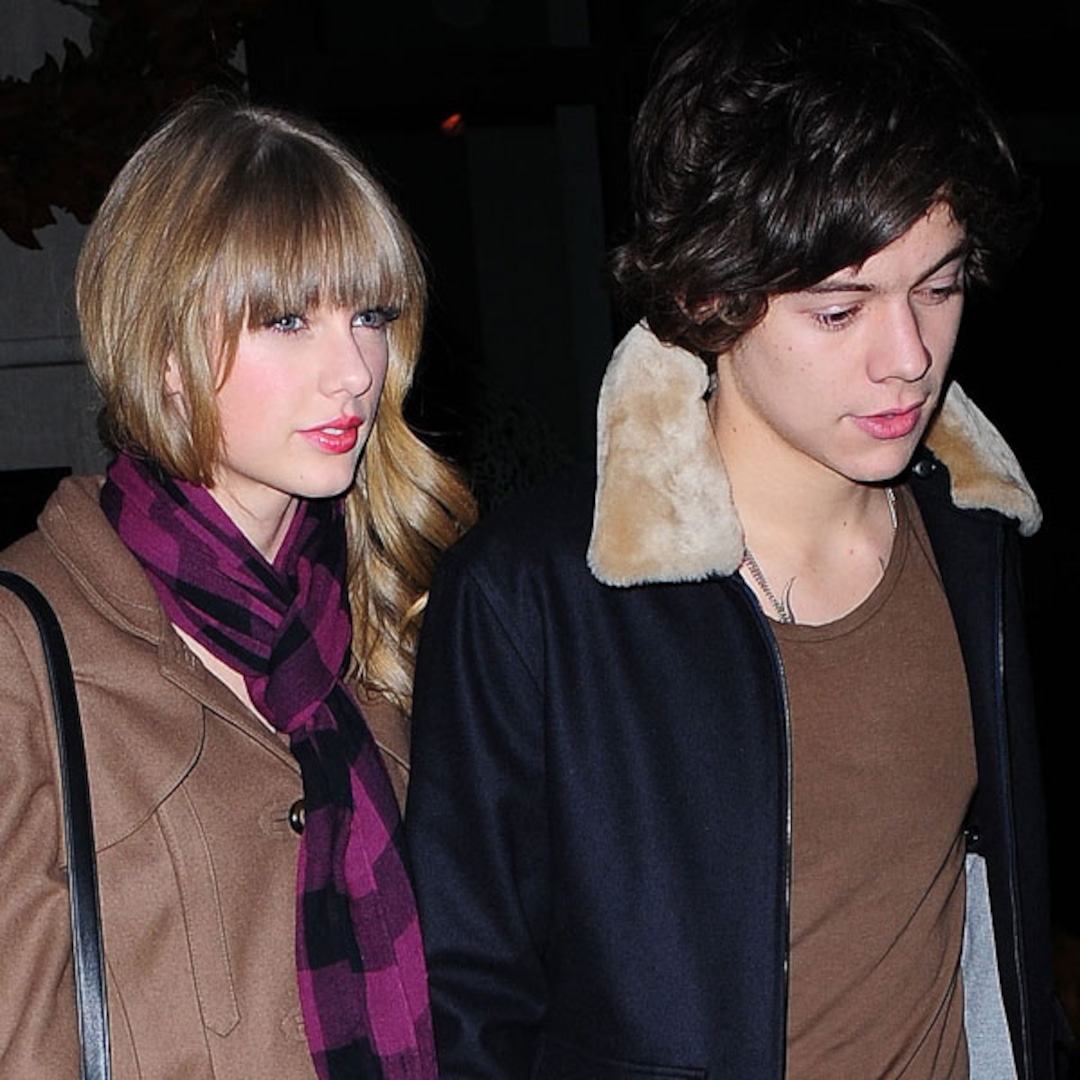

Unpacking Taylor Swift’s Conceptual Boyfriends: The Timeless Enigma Behind Her Boyfriends Revealed

Unlocking the Science of What We Eat: Key Insights from Discovering Food and Nutrition Student Workbook Answers

What Time Do Longhorns Play? Decoding the Texas A&M Football Schedule

Transform Your Weekly Plans with Iheartpublix Weekly Ad — Your Key to Smart, Savvy Living