Trigonal Pyramidal Geometry Unlocked: Why Bond Angles Matter in Molecular Shape

Trigonal Pyramidal Geometry Unlocked: Why Bond Angles Matter in Molecular Shape

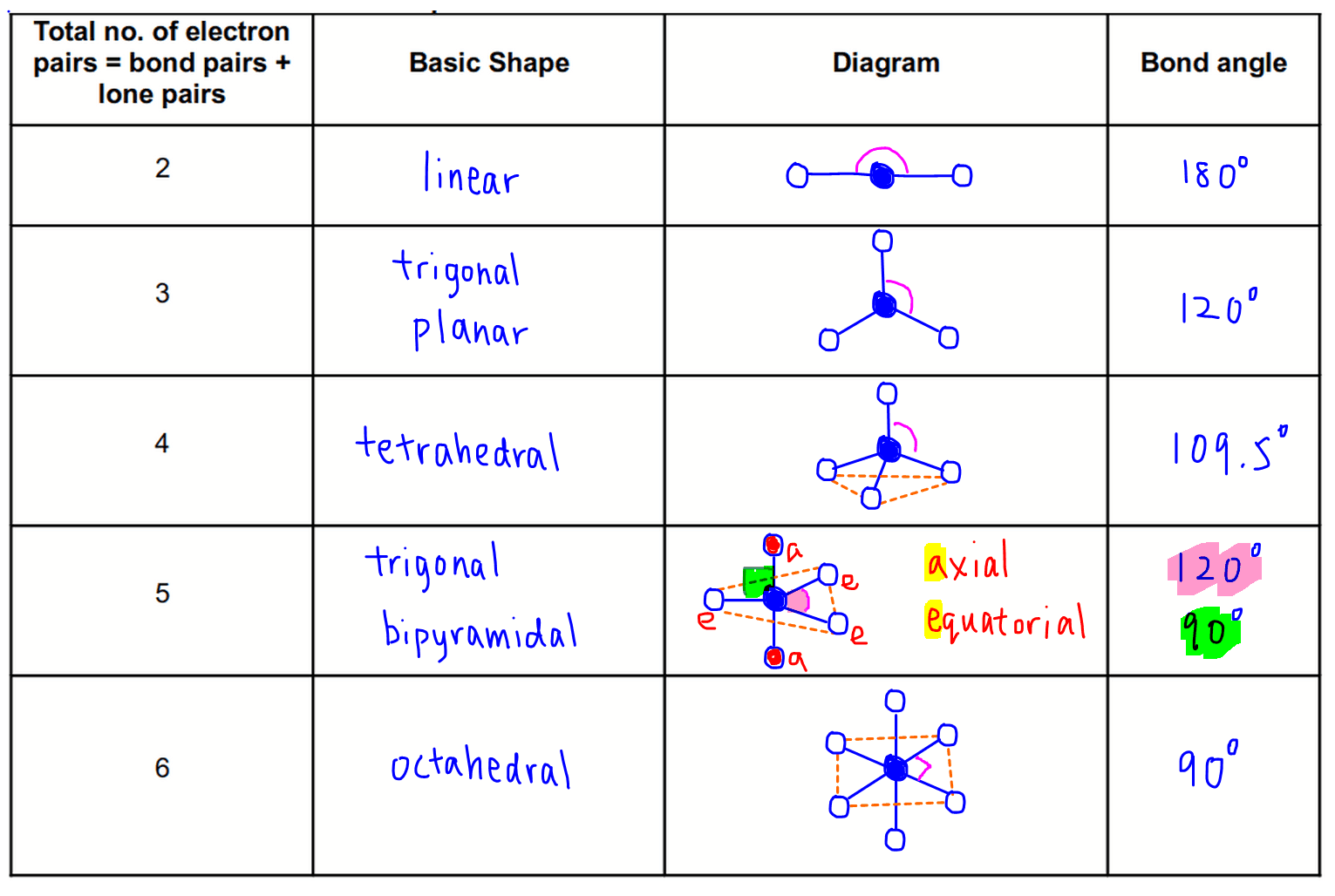

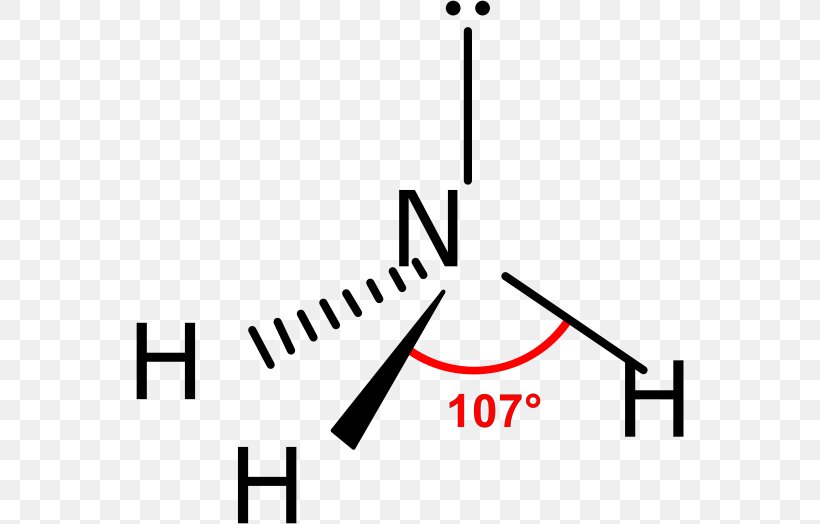

Deadly accuracy in molecular structure hinges on one fundamental concept: the bond angle of trigonal pyramidal. This geometric arrangement, defined by a central atom bonded to three other atoms and a lone pair of electrons, governs how molecules fold in space—shaping everything from ammonia’s reactivity to the stability of complex biomolecules. The precise bond angle, typically around 107° in trigonal pyramidal configurations, arises from electron repulsion forces dictated by VSEPR theory.

Unlike ideal tetrahedral angles of 109.5°, the contraction reflects lone pair repulsion, altering molecular packing and reactivity in subtle yet profound ways. Access the heart of this phenomenon through bond angle—the angle formed between two bonded atoms at the central node. In a perfect trigonal pyramidal geometry, this angle is never exactly 109.5° due to the lone pair’s stronger electron density pushing bonding pairs closer together.

This deviation is not a flawbut a signature of electron pairing dynamics. Understanding this angle reveals far more than geometry—it exposes the invisible hand of electron repulsion that dictates molecular behavior.

The Science Behind Trigonal Pyramidal Bond Angles

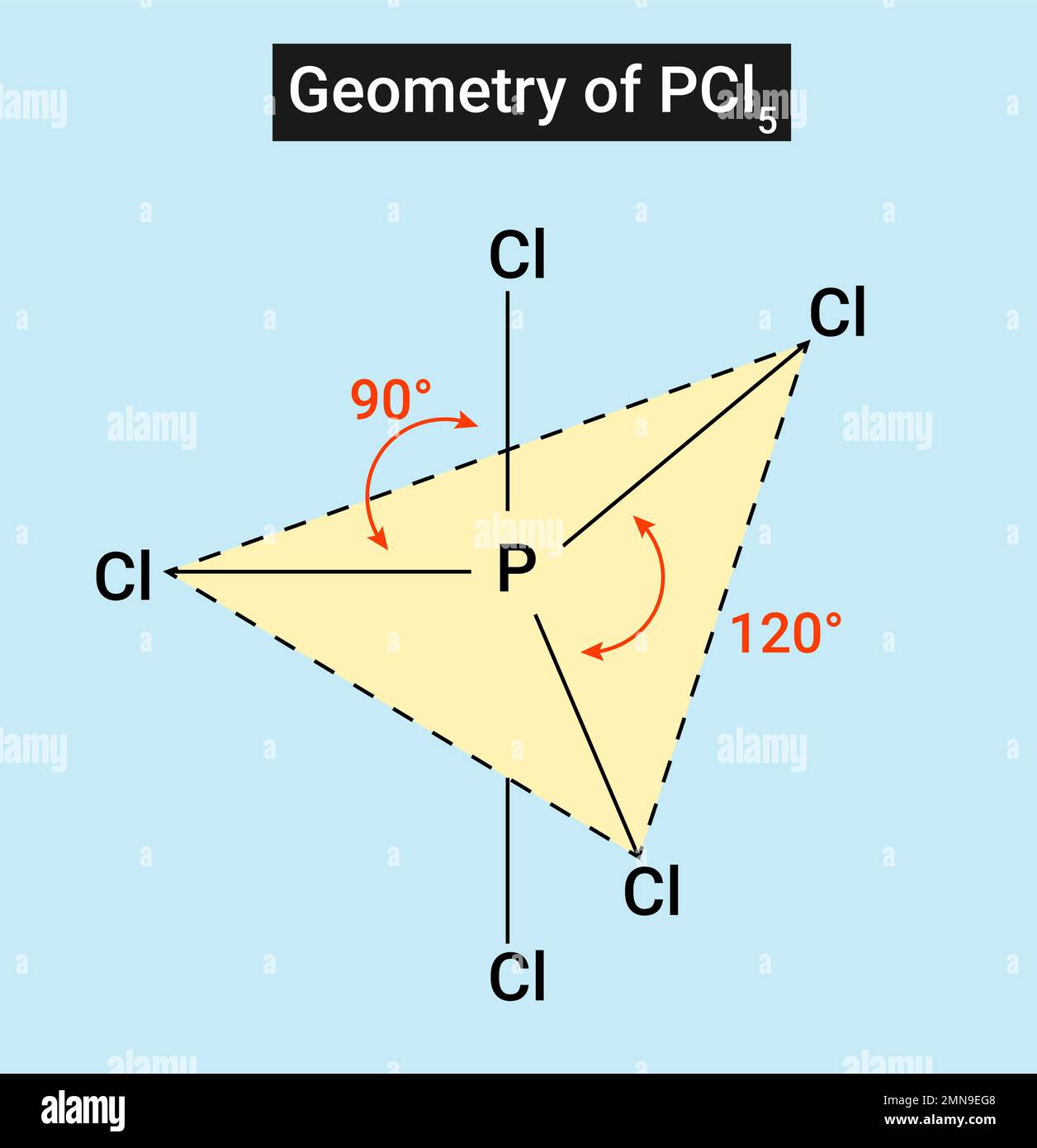

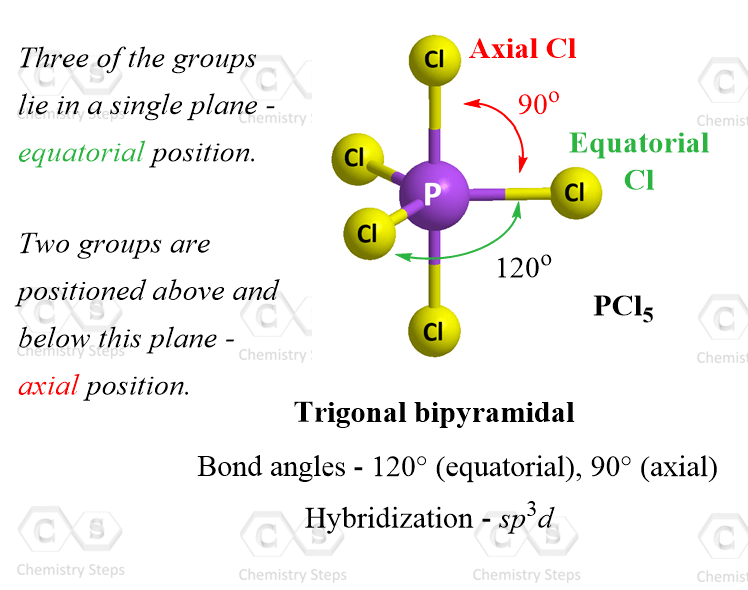

At the core of the trigonal pyramid lies a central atom, such as nitrogen in ammonia (NH₃), bonded to three surrounding atoms and hosting one unshared electron pair.The VSEPR (Valence Shell Electron Pair Repulsion) model explains how electron domains—both bonding pairs and lone pairs—repel each other to minimize energy. Each bond and lone pair occupies a region of electron density, with the lone pair exerting greater repulsive force than bonding pairs. This asymmetry compresses the axial angles between bonded atom pairs, resulting in a bond angle less than the ideal tetrahedral value.

Why the Angle Shrinks The lone pair’s stronger repulsion stems from its closer proximity and higher energy state relative to bonding pairs. Electron clouds repel with increasing strength as they are compressed into a smaller space, diminishing the repulsion between bonded pairs. This "pinching" effect reduces the bond angles to approximately 107°—a value observed consistently across trigonal pyramidal molecules like NH₃, PH₃, and CH₃Cl.

This angle is not arbitrary; it reflects a delicate equilibrium where quantum mechanical forces balance steric strain and electronic stability.

Examples of Trigonal Pyramidal Molecules and Their Bond Angles

Ammonia (NH₃) stands as the most textbook example. With three N–H bonds and one lone pair, its bond angle is measured at ~107.3°, slightly narrower than 109.5° due to lone pair compression.Similarly, the phosphine molecule PH₃ adopts a trigonal pyramidal geometry, but its bond angle is notably smaller—closer to 93.5°—because the larger phosphorus atom introduces additional steric congestion, intensifying lone pair effects. Even in organic chemistry, methylamine (CH₃NH₂) displays this geometry, with NH₂ groups maintaining a bond angle near the ideallectual 107°, influencing hydrogen bonding and solubility. These variations underscore a critical principle: while the ideal geometry hints at 109.5°, real bond angles adapt to atomic size, electronegativity, and lone pair character.

The shift from ideal to real angles is measurable and meaningful, offering chemists precise diagnostic tools for predicting molecular shape and function.

Impact on Chemical Reactivity and Molecular Interactions

The bond angle of 107° in trigonal pyramidal structures profoundly influences chemical reactivity. In ammonia, the compressed angle creates a pronounced molecular dipole—bonded hydrogen atoms accumulation near the electron-deficient nitrogen lone pair enhances nucleophilicity.This geometry enables NH₃ to readily donate the lone pair, making it a key reactant in acid-base chemistry and industrial processes like ammonia synthesis. In biological systems, the trigonal pyramidal bond angle governs hydrogen bonding networks. The spatial arrangement of donor and acceptor hydrogen atoms affects protein folding, enzyme binding, and DNA base pairing.

Even in charged intermediates—such as nitrogen-centered transition states during catalytic hydrolysis—the angle determines steric accessibility and orbital alignment, directly impacting reaction rates and selectivity. Lone pair geometry also dictates molecular symmetry and polarity. For example, in enamine formation, the pyramidal distortion alters π-delocalization patterns, modifying electronic distribution and reactivity toward electrophiles.

Thus, understanding bond angles transcends descriptive geometry—it becomes predictive of function.

Measuring Bond Angles: Tools and Techniques in Modern Chemistry

Determining the bond angle of trigonal pyramidal molecules requires precise experimental and computational methods. X-ray crystallography remains the cornerstone, revealing atomic positions in solid-state crystals with sub-angstrom resolution.By locating bond lengths and angles, researchers confirm both idealized and real-world deviations. Modern synchrotron radiation enables real-time tracking of structural changes under varying temperature or pressure, shedding light on dynamic conformational shifts. Computational chemistry complements experiments through quantum mechanical modeling

Related Post

Who Owns The New York Times? Unpacking the Paper’s Complex Ownership Structure and Publishing Legacy

College Algebra Concepts Through Functions 5Th Edition

Prmovies Online Movies: Your Ultimate Guide to Flawless Streaming

Everything You Need to Know About Drhomeycom: Mastering Quick & Secure Login Access