Turing's Vision: Computing Machinery And Intelligence (1950)

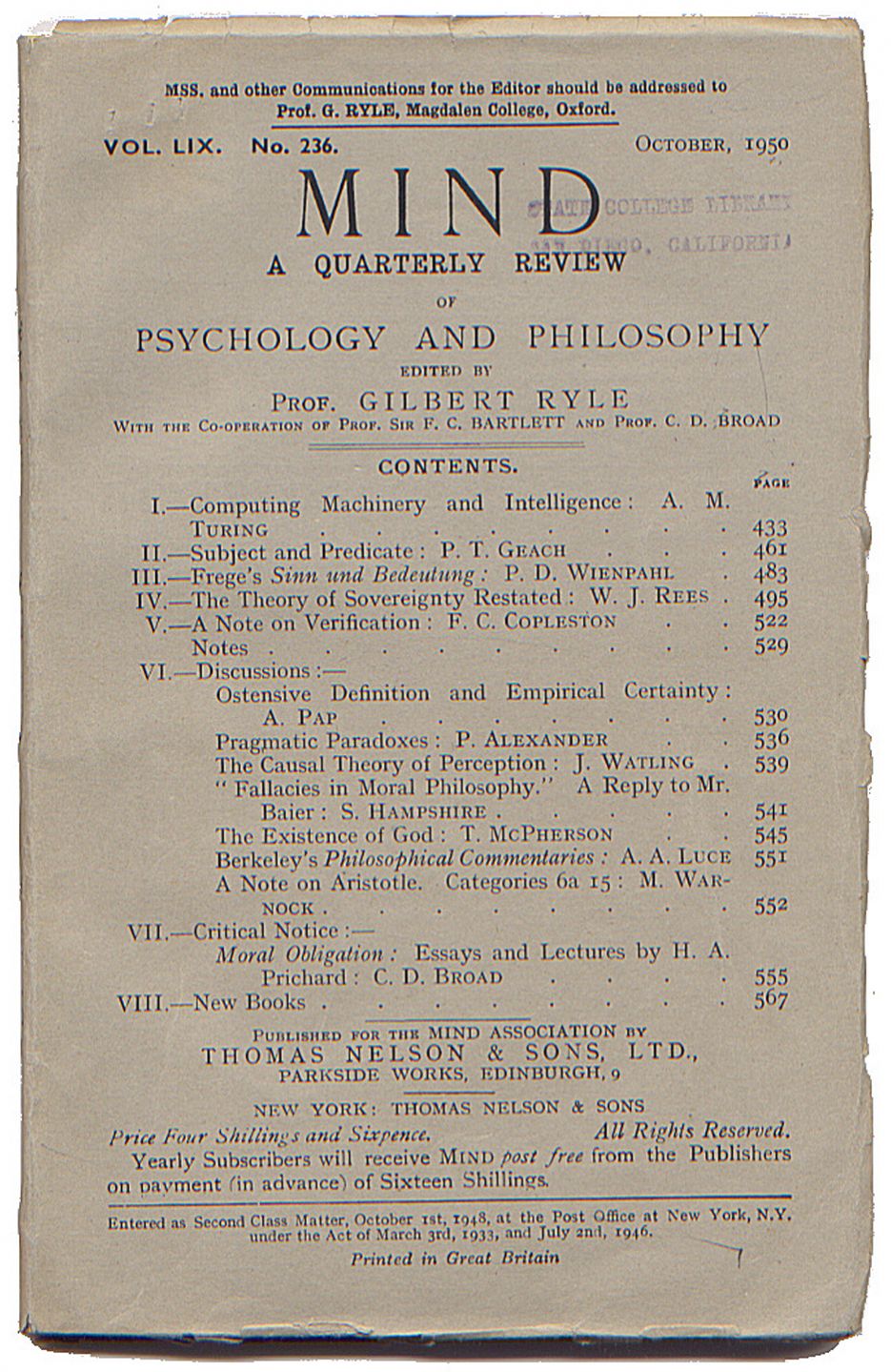

In 1950, Alan Turing donned philosophical armor to dissect one of humanity’s greatest frontiers: whether machines could think. Published in the landmark paper Computing Machinery and Intelligence, Turing’s visionary inquiry laid not just the foundation for artificial intelligence but redefined how we understand intelligence itself—machines, minds, and the boundaries between. At a time when computation was seen mostly as number crunching, Turing prompted a radical shift: what if thinking could be simulated?

His question—“Can machines think?”—ignited over seventy years of exploration, automation, and profound societal transformation.

At the heart of Turing’s argument was a bold challenge to traditional definitions of intelligence. He famously proposed the *Imitation Game*, a thought experiment later dubbed the Turing Test. In it, a human judge engages in natural language conversations with both a machine and another human, unaware which is which; if the machine remains indistinguishable, it is said to demonstrate intelligent behavior.

Turing wrote, “We are here asking the question: Can machines think?”—a deceptively simple question carrying seismic implications. He rejected rigid criteria, urging instead to evaluate intelligence through observable performance, marking a decisive break from metaphysical dogma.

Redefining Intelligence Beyond the Biological

Turing’s vision shattered the assumption that intelligence is exclusively biological or conscious. He recognized that thought might emerge not from organic neurons but from symbolic manipulation governed by rules—processes machines could replicate.

This insight opened a new epistemological space: intelligence as an emergent property of information processing, not a unique spark of life. His test invited inquiry into function over form, a perspective that underpins modern AI systems capable of language, reasoning, and even creative expression—doing so without self-awareness, humor, or intent.

The Technical and Philosophical Foundations

Beyond philosophy, Turing’s work was deeply technical. As compiler and pioneer of algorithmic learning, he envisioned systems that adapt through experience—early forerunners of machine learning.

His proposal implies that a machine’s “thought” operates at the level of pattern recognition and response generation, not subjective experience. This functionalist approach shifts focus from *what* a machine thinks to *how* it behaves under scrutiny. Yet Turing was cautious: he warned that intelligence must be judged by outcomes, not assumptions.

As he stated, “The excuse ‘I cannot prove it’ will not stand.” This demand for empirical validation remains a cornerstone of AI evaluation today.

Legacy and the Evolution of Thinking Machines

Turing’s paper ignited decades of innovation. From early symbolic AI in the 1950s and 60s to today’s deep learning algorithms, his questions echo in every self-driving car, voice assistant, and recommendation engine. The Turing Test, though debated, inspired frameworks for assessing machine cognition, notably the Loebner Prize and modern benchmarks in natural language processing.

Yet critics argue the test oversimplifies consciousness—focusing on mimicry rather than understanding. Still, its intent endures: to measure whether artificial systems can replicate, or even rival, human cognitive flexibility.

Real-world applications now reflect Turing’s far-reaching influence. AI excels at recognizing faces, translating languages, composing music, and diagnosing diseases—tasks once deemed exclusive to human minds.

In healthcare, machine learning models detect tumors with radiologist-level accuracy. In finance, algorithmic traders execute decisions at speeds no human can match. These systems process vast data streams, learn from patterns, and adapt—operating less like “thinking” and more like hyper-efficient pattern processors, yet achieving results indistinguishable from intelligence.

Ethical and Philosophical Challenges

While AI delivers transformative benefits, Turing’s questions raise urgent ethical dilemmas.

Can a machine truly “understand,” or is it merely simulating? Do we assume human-like states where none exist? Philosophers debate whether passing the Turing Test confers moral agency.

For now, machines lack consciousness, emotions, and subjective experience—tools that define human agency. Yet as AI systems grow more autonomous, society grapples with accountability, bias, and the long-term consequences of delegating decision-making to machines. Turing’s vision forces us to ask not only if machines can think, but what it means to *be* intelligent—and what responsibilities we bear in designing such systems.

Related Post

Trending Now: The Hottest Topics Shaping Global Conversations in 2024

MLB Parks Bullpen Your Ultimate Guide: Master the Art of Late-Game Dominance

Breaking: Barron Trump Vanishes Without a Trace—President Trump Issues Rare Silence on Son’s Disappearance

.png?format=1500w)

Cómo Ver SpongeBob Hoy en Español: Guía Definitiva para Disfrutar la Serie