Understanding Currency Swaps in Finance: How They Reshape Global Markets and Risk Management

Understanding Currency Swaps in Finance: How They Reshape Global Markets and Risk Management

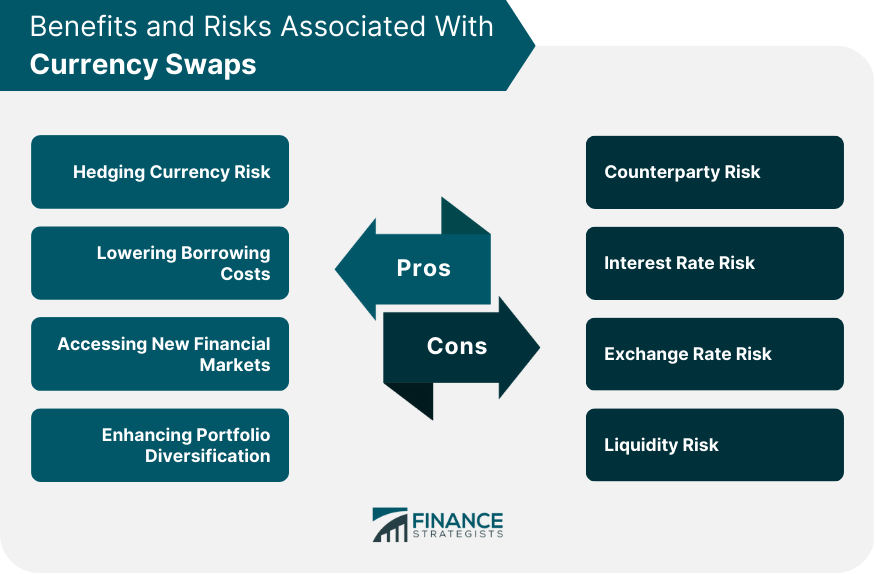

At the heart of modern international finance lie currency swaps—sophisticated financial instruments that enable borrowers, investors, and corporations to manage foreign exchange exposure, reduce borrowing costs, and access more favorable funding markets. More than just currency exchanges, these agreements are structured facilitators of long-term financial stability in an interconnected world. This comprehensive guide unravels the mechanics, purposes, types, and real-world applications of currency swaps, offering clarity on their role in shaping global capital flows and financial strategy.

What Days Define Currency Swaps? Currency swaps are financial agreements where two counterparties exchange principal and interest payments in different currencies over a specified term. Unlike forward contracts, which settle at a fixed future date, swaps involve multi-period cash flows—often spanning several years—allowing parties to hedge against currency fluctuations, align debt with revenue currency, or optimize financing costs. The arrangement spans four core elements: notional principal (not exchanged, but used to calculate payments), fixed or floating interest rates, regular payment intervals, and a predefined maturity date.

Each swap typically features an initial swap of principal amounts at parity, followed by simultaneous payment of interest in respective currencies, ending in a reverse principal exchange to restore the original principal. “Currency swaps are the invisible engines of global finance,” notes financial expert Elena Marquez, “enabling firms to access cheaper funding in markets where local interest rates are more favorable—without enduring currency risk unnecessarily.”

Types of Currency Swaps: Illuminating Mechanisms Behind the Curve

Currency swaps manifest in several distinct forms, each tailored to specific financial needs. The two primary categories are:

- Fixed-for-Floating Currency Swaps: One party agrees to pay a fixed interest rate in one currency while receiving a floating rate (e.g., USD Libor) in the other, with both principal amounts returned at maturity.

Widely used by multinationals managing variable-rate liabilities.

- Bilateral and Triangular Swaps: Bilateral swaps involve two parties exchanging principal and interest, often to netting exposure. Triangular swaps, involving three entities, facilitate complex cross-border funding—such as Company A borrowing in EUR, swapping with Company B in JPY, and all settling via a single intermediary to simplify settlement and reduce counterparty risk.

The Core Functions: Why Institutions Embrace Swaps

Currency swaps serve as powerful tools for managing multiple financial exposures. Key functions include:

- Currency Risk Hedging: Multinational corporations and investors use swaps to protect against adverse exchange rate movements. A U.S.-based firm financing a European subsidiary in euros might swap EUR receivables into USD payments to stabilize earnings.

- Cost Arbitrage in Global Markets: Accessing cheaper debt structures across borders allows firms to optimize their capital costs.

For instance, a Japanese company may secure USD funding at lower interest rates via a swap and swap back to JPY—bypassing foreign borrowing penalties.

- Liquidity Management and Balance Sheet Stabilization: Banks and sovereign entities deploy swaps to adjust usable liquidity in desired currencies without triggering trigger sales during market stress.

- Strategic Portfolio Diversification: Institutional investors use swaps to gain exposure to foreign markets without physical currency conversion, improving diversification and reducing transaction frictions.

Mechanics and Pricing: How Cash Flows Are Calculated

At the operational core, currency swaps rely on predictable cash-flow models. Each party calculates periodic interest obligations using agreed rates and daytime exchange rates for principal conversions—often standardized on major liquidity benchmarks like USD, EUR, or JPY. The effective cost difference between currencies drives the net present value of expected cash flows.

Swap pricing integrates several factors:

- Interest Rate Differentials: Widening spreads between theme currencies’ benchmark rates directly impact swap value and acceptability.

- Currency Volatility: Higher volatility increases risk premiums but also potential gains from favorable rate shifts.

- Credit Spreads and Counterparty Risk: Even if rates align, perceived counterparty default risk influences swap terms—especially in over-the-counter (OTC)

Related Post

CVS Unlocks Extended Easter Hours: What Shoppers Need to Know for the 2024 Season

Download Instagram Stories on Your Desktop with Indownio — Speed, Simplicity, and Seamless Workflow

Archer Cast: Redefining Talent Scouting in the Modern Entertainment Industry

Breckie Hill Fans: The Rising Star and Her Explosive Community Growth