X-Shaped Molecular Architectures: Unlocking the Geometric Blueprint of Electron and Molecular Geometry

X-Shaped Molecular Architectures: Unlocking the Geometric Blueprint of Electron and Molecular Geometry

At the intersection of quantum mechanics and visual chemistry lies a compelling geometric puzzle: molecules shaped like the X—where electron repulsion and atomic arrangement converge in defining X-shaped molecular geometries. These molecular forms are not mere curiosities; they represent critical configurations dictated by VSEPR theory, profoundly influencing chemical reactivity, polarity, and intermolecular interactions. The X-shaped geometry emerges when electron pairs around a central atom repel each other with exceptional symmetry, typically in electron domains that include lone pairs and bonding pairs arranged at nearly 120-degree angles.

This configuration finds power in its simplicity and symmetry, offering a foundation for understanding molecular behavior across diverse chemical systems.

Central to deciphering X-shaped structures is embracing the VSEPR model—Valence Shell Electron Pair Repulsion—which predicts molecular shape based on the repulsive forces between electron domains. In X-shaped molecules, five electron pairs—often one lone pair and four bonding pairs—favor a geometry where two pairs occupy opposite axial positions, while the other two form 120-degree equatorial bonds, forming the classic X silhouette.

This arrangement minimizes electron collision and stabilization, as exemplified in well-known compounds like chlorine trifluoride (ClF₃) and ozone (O₃), though ozone’s bent form is sometimes X-like due to lone pair distortions.

The Core Principles of Electron Geometry

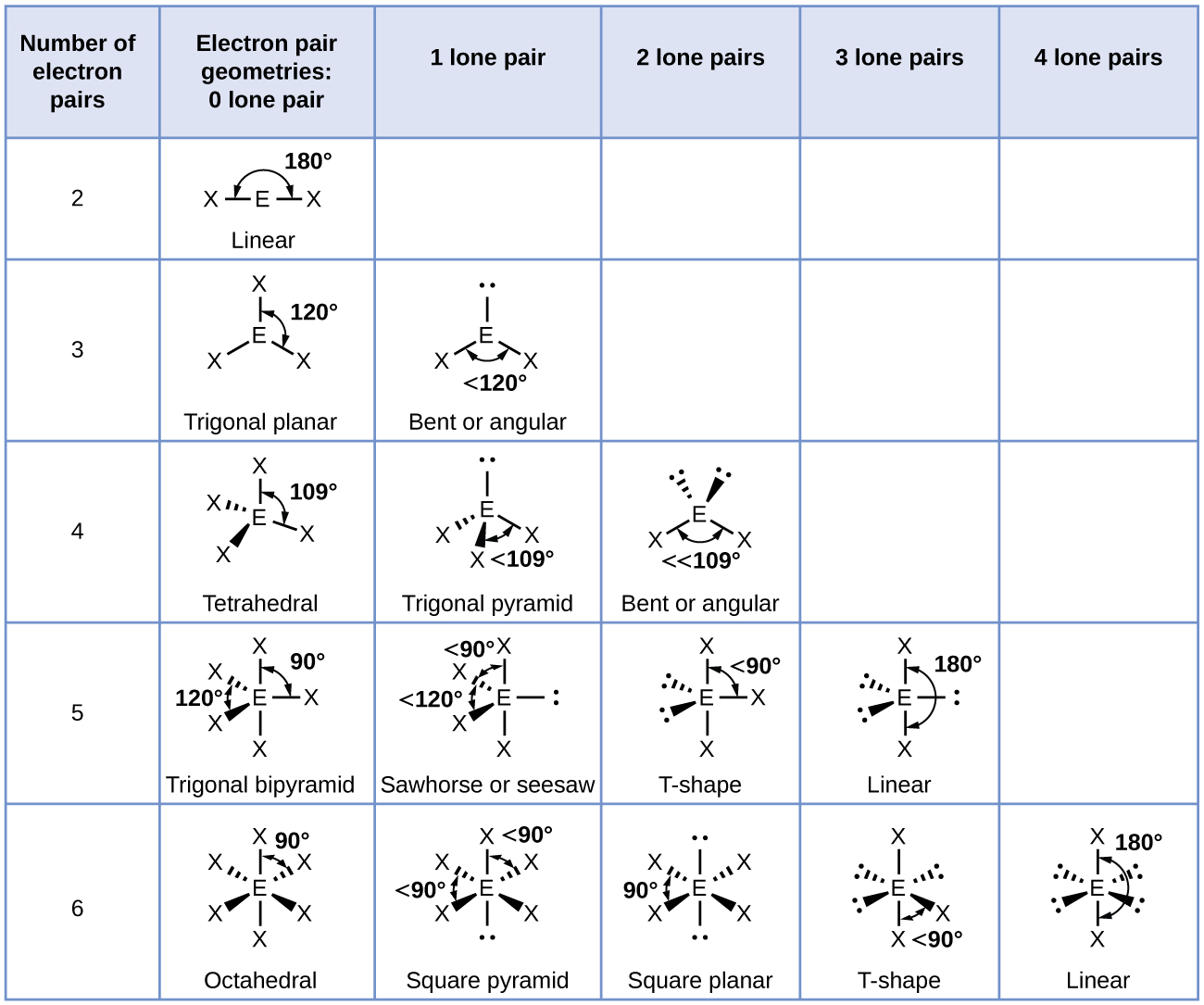

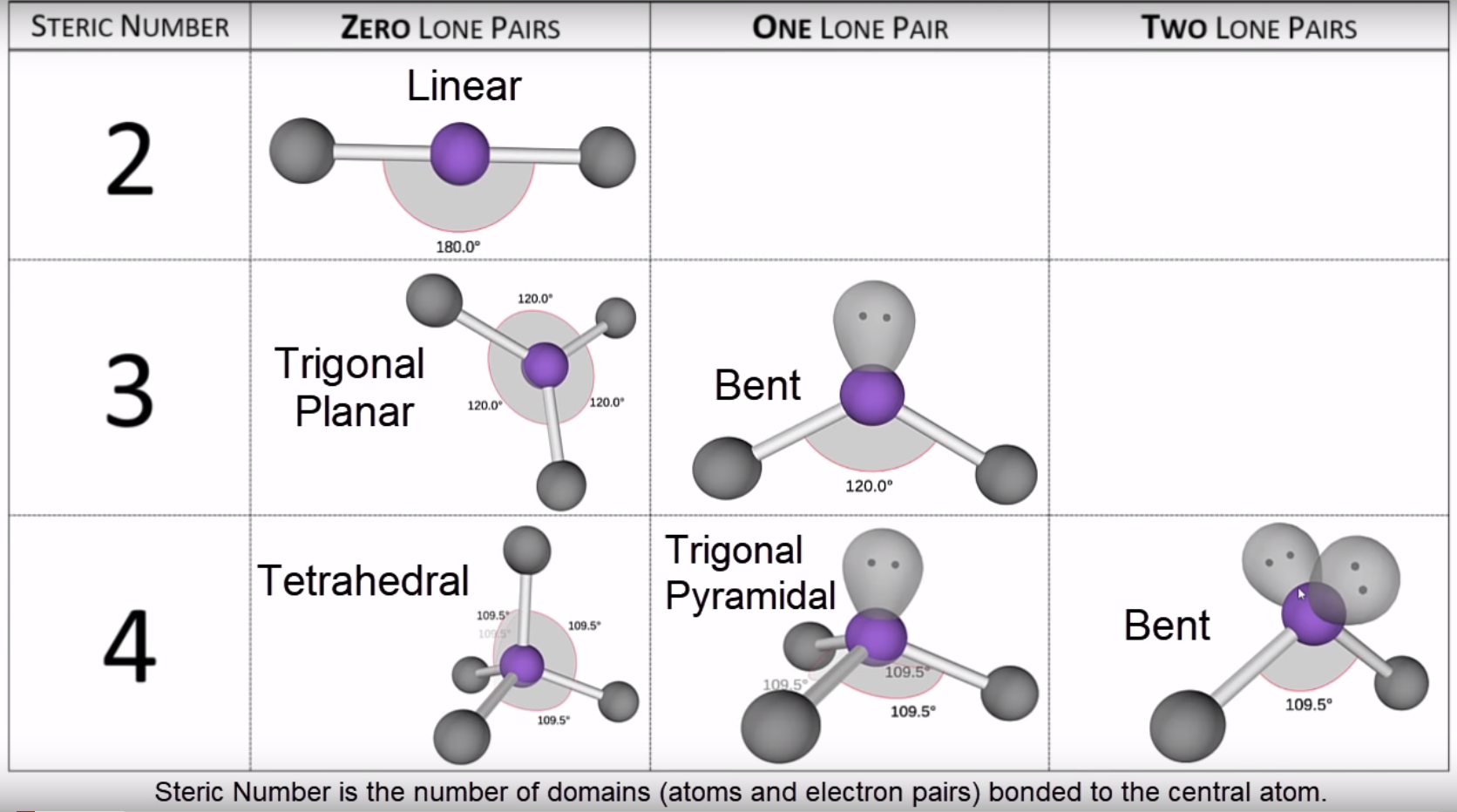

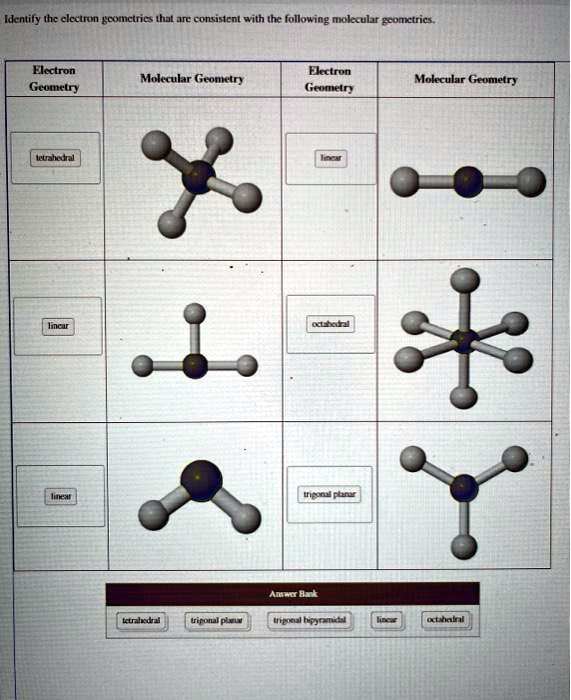

Electron geometry describes the three-dimensional spatial distribution of electron repulsions around a central atom, independent of molecular shape alone. When three or more electron domains—be they bonding pairs or lone pairs—occupy regions around a central atom, their mutual repulsion dictates the preferred spatial orientation.The X-shaped configuration arises when four domains (three bonding, one lone pair) adopt a trigonal bipyramidal electron layout, with two bonding pairs occupying axial positions and the remaining two equatorial positions forming the angular, symmetric arms of an X. Electron Geometry—The Foundation of Structure In a trigonal bipyramidal arrangement—the most common precursor to X-geometry—distinct position types exist. Axial positions are aligned vertically, each separated by 180 degrees through the center, while equatorial positions form a triangular plane at 120 degrees from each other, straddling the equator.

This geometric dualism enables the X shape: two equivalent bonding or lone pairs occupy opposite axial sites, and the remaining two—in this case, bonding—reside in the equatorial plane, angled at 120 degrees, forming a symmetric X with maximal symmetry but distinct polarity. Electron geometry emphasizes only repulsion forces—no explicit bond angles or molecular polarity—yet it underpins molecular behavior. For instance, ClF₃’s X-shaped electron configuration (AX₃E₂) leads to a highly asymmetric molecular geometry with pronounced tug-on-polarity, despite central atom symmetry.

The separation of lone and bonding pairs creates regions of distinct electron density, contributing to the molecule’s extreme fluorine deficiency and hyperfluorine character.

Electron geometry, therefore, provides the invisible scaffold upon which molecular identity is built—revealing how atomic arrangements are shaped by fundamental repulsive forces long before chemical bonds form.

Molecular Geometry: The X-Shaped Arrangement in Action

When electron domains condense into actual bonds and lone pairs, molecular geometry emerges through precise spatial tuning of these forces.The X-shaped molecular form is unique in its double-axis symmetry, making it visually striking and chemically significant. It appears in molecules where five electron domains fold into a hybrid structure with two axial and two equatorial bonds—but not all such structures yield identical X shapes. Critical Factors Shaping the X Silhouette - **Lone Pair Dominance:** Lone pairs exert stronger repulsion than bonding pairs, compressing adjacent bonding angles and skewing geometry toward X-like asymmetry, even within otherwise symmetric frameworks.

- **Bond Pair Duality:** When two bonding pairs occupy axial sites and two reside in equatorial positions, their 120-degree alignment fosters the characteristic angular branches of an X. - **Angle Balance:** The angular positioning maintains symmetric separation—often approximating 120 and 180 degrees—yielding a globally balanced X without central symmetry. Take ozone (O₃): though often described as bent, its resonance-stabilized structure exhibits X-like electron density distribution, with lone and bond pairs positioned to minimize repulsion in a barely bent, X-oriented framework.

Similarly, ClF₃’s trigonal bipyramidal electron geometry—AX₃E₂—presents two axial F atoms and two equatorial Cl–F bonds arranged at 117.5° (close to 120°), producing a clear X outline in molecular space.

The precise alignment within X-shaped geometries influences more than visuality—it governs molecular reactivity. Boosting understanding of these configurations enhances predictions about molecular polarity, dipole moments, and interaction potential.

For example, an X-shaped molecule like IF₃ (trigonal bipyramidal, AX₃E) presents polar C–F bonds at offset angles, preventing dipole cancellation and enhancing overall molecular polarity—key for solubility and intermolecular bonding. Real-World Applications and Chemical Significance In atmospheric chemistry, X-shaped trace species such as NO₂ (dinitrogen dioxide) exhibit vibrational modes sensitive to bond length and symmetry, impacting infrared absorption and climate-relevant reactivity. Similarly, in synthetic chemistry, X-shaped intermediates—like those in transition-state mechanisms—dictate stereochemical outcomes through steric and electronic control.

Their balanced angular momentum supports predictable catalytic cycles in industrial processes, from polymerization to environmental remediation.

Across disciplines, from perfumery to pharmaceutical design, mastering X-shaped molecular geometries equips scientists with predictive tools. By decoding how electron placement sculpts molecular form, researchers anticipate shape-dependent behaviors—tuning reactivity, stability, and function with unprecedented accuracy.

The X-shaped geometry, rooted in fundamental VSEPR principles, transcends mere structure to become a dynamic framework for chemical insight.Its symmetries and asymmetries, governed by electron repulsion, underpin molecular identity, polarity, and reactivity—making it a cornerstone of modern chemical understanding. As both a visual signature and predictive model, electron and molecular geometries X-shaped form the invisible scaffolding upon which chemistry’s complexity is built.

Related Post

Cars 3 Cast: The Driving Force Behind a Steel-Tested Heart and Soul

Explore San Diego Zoo Like Never Before with the Official Interactive Map

Harrison Ford’s Age in Star Wars: The Stardom That Spanned Three Generations

Darlington County’s Bold Snapshot: Scarborough’s Matthew Lee Mugshot Goes Viral After 08-30-2022 Bust